Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Monday, 1 February 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

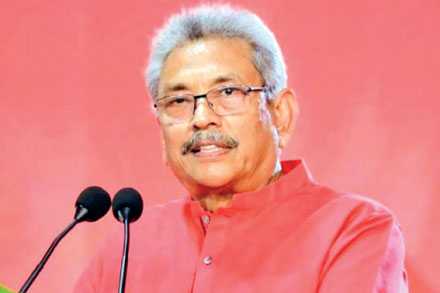

President Gotabaya Rajapaksa

Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa

Foreign Minister Dinesh Gunawardena

Foreign Secretary Admiral Jayantha Colombage

By Chandani Kirinde

Sri Lanka’s head is once again on the UNHRC’s chopping block, as it has been pretty much since May 2009; but this year, the country seems a lot closer to being struck a severe blow. It is not entirely unexpected, given the Government’s decision last February to withdraw from the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) Resolution 30/1 and others adopted after 2015. This Resolution was co-sponsored by Sri Lanka under the previous Government.

While withdrawing from the Resolution, the Government reiterated that Sri Lanka will continue its engagement with the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and UN Human Rights mechanisms, and work in close cooperation with the international community “through capacity-building and technical assistance in mutually agreed areas, in keeping with domestic priorities and policies”.

But how sincere has the Government been about engaging with UN human rights bodies and how prudently has its foreign policy handlers managed relations with the International Community (IC) since taking office? It is no secret that the wrath of some major international powers was directed at Gotabaya Rajapaksa long before he became President and there is little doubt, he was aware his election would reignite calls for war crimes investigations, particularly in countries where LTTE lobbyists are hard at work. Hence there was the need to prioritise foreign/ diplomatic relations early on and work closely with the UN as well as international partners on this issue.

Instead, we have not seen an urgency on the part of the Government to do so. International relations were put on the back burner and instead of working to win over those who may have had reservations about how to handle relations with the new administration, the Government has managed to alienate the country’s traditional allies in the Middle East and Muslim-majority countries by sticking stubbornly to a ‘cremations only’ policy for COVID-19 victims, earning for the country the dubious honour of being the only nation in the world to do so.

In May last year, Ambassadors and High Commissioners of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) states in Sri Lanka wrote to President Gotabaya Rajapaksa regarding the cremations only policy of the Government. The letter said: “We strongly believe that this matter must not arise as an issue and reach across Muslims elsewhere as such and dent the impeccable standing of a pluralist, inclusive and harmonious Sri Lanka,” while adding that they are of the view that this is a matter that can (and needs to) be addressed forthrightly through frank consultation with the Muslims of Sri Lanka under the leadership of the President and Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa.

The letter was signed by the Ambassadors of the Sultanate of Oman, the State of Palestine, Kuwait, Indonesia, Egypt, United Arab Emirates, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Afghanistan and Turkey as well as the High Commissioners of the Maldives, Pakistan, Malaysia and Bangladesh while the Chargé d› Affaires of Libya, Iran and Iraq, too, signed the letter.

Among the signatories to this letter are countries, including Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Indonesia, and Malaysia, that voted in support of the UNHRC resolution on ‘Assistance to Sri Lanka in the promotion and protection of human rights’, which was adopted by the HRC in May 2009, a resolution highly favourable to the country, which came soon after the end of hostilities with the LTTE.

Several of these countries make up the current membership of the 47-member HRC but given the scant regard the Government has paid to their sentiments on the issue of cremations, these countries are unlikely to side with Sri Lanka at a particularly crucial time. A pointer could be Saudi Arabia’s delay in accepting the nomination of Sri Lanka’s Ambassador-Designate Ahamed Jawad, whose name was cleared by the High Post Committee (HPC) of Parliament in early November last year.

Since then, the United States and the European Union (EU), too, have voiced concerns over the ‘cremations only’ policy with a report by a group of UN experts saying the “imposition of cremation as the only option for handling the bodies confirmed or suspected of COVID-19 amounts to a human rights violation”.

Closer to home, too, the Government has failed to get its diplomatic act in order. The Sri Lanka High Commission in New Delhi, the most coveted and important outing for a Sri Lankan diplomat, has been headless for over a year since its last incumbent was recalled after the election of the President in November 2019.

One-time politician and businessman Milinda Moragoda was picked to head the High Commission and his name was cleared by the HPC last September, but he remains in Colombo while others approved along with him, including to the USA (Ravinath Aryasinha for Washington and Mohan Peiris for New York), Beijing (Palitha Kohana), and Geneva (C.A. Chandraprema), have taken up their posts.

Leaving the top post in New Delhi vacant for over a year, particularly at a time when Indo-Lanka relations are being pushed against the wall once again, does little to strengthen relations between the two countries.

With powerful voices from within the Government calling for the repeal of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution and abolition of the provincial council system, and with the continuing stalemate over Government plans to develop the Colombo Port’s Eastern Container Terminal (ECT) as an investment project with Sri Lanka having 51% ownership and the remaining 49% with an Indian investor, relations can only get rocky in the months ahead.

India, too, is a member of the HRC in the current cycle; and for a government faced with an uphill fight at the upcoming sessions, what is needed is the unstinted support of its allies. But how well it is handling its relations with the country’s closet neighbour leaves a lot to be desired and does not augur well for the future.

Playing possum

In the meantime, in what is obviously a time-buying exercise to ward off mounting pressure from the UNHRC, the President appointed a three-member commission in mid-January to identify the findings of the preceding commissions and committees that probed human rights violations and inquire into the progress in the implementation of their recommendations.

The chances are remote that the appointment of yet another commission to investigate human rights violations will appease either the UNHRC or its members who are calling for meaningful measures on the part of the Government to address allegations of past rights violations and new fears over curbs to freedom of expression, worship, and other rights.

As far as foreign relations go, the Government cannot afford to play possum only to awaken when the next session of the HRC is about the start or when the country is facing a diplomatic crisis. Diplomacy is about constantly engaging with the international community, even on contentious issues like human rights.

Given the sensitivity of the war crimes/human rights violations issue on the domestic front, any government in power will move cautiously in dealing with allegations levelled at members of the armed forces but disengaging with stakeholders and the international community on such issues will not make them go away.

With less than three weeks before the UNHRC sessions begin in Geneva, the Government needs to demonstrate it is sincere about engaging with members of the IC and the UN on issues of concern to them and not create new issues that would exacerbate an already precarious situation.