Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Monday, 2 April 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Sajeeva Samaranayake

Dr. W. A. Wijewardena, who is one of our ‘user friendly’ public intellectuals must be applauded for presenting two view-points on grooming future intellectuals – one from Thailand (Prof. Worsak President of AIT) and the other from Chapa Bandara – an unconventional intellect brought into open the minds of Economics undergrads at University of Sri Jayawardenapura on the Sri Lankan economy and our strategic options for the future.

My humble additions below, as a disciple and practitioner of training as opposed to teaching, is to add a perspective, taken for granted, and develop further questions and pointers for developing this essential discussion. The recent race riots, and their resounding confirmation that ‘peace’ is defined by consciousness, serves to further illuminate these aspects. The Colombo Ted talk of Peter D’Almeida entitled ‘An ounce of consciousness is worth a ton of creativity’ (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C9OmN9O_v8U) refines this focus further. First, how do we see ourselves?

The emotional human being…

The conscious human being today is struggling to make sense of reality; struggling to change it. The Dalai Lama said this about the downside of global citizenship – in 1976:

“The present generation are living in this world under great pressure, under a very complicated system, amidst confusion. Everybody talks about peace, justice, equality but in practice it is very difficult. This is not because the individual person is bad but because the overall environment, the pressures, the circumstances are so strong, so influential.” [Dalai Lama, H.H.XIV, “Universal responsibility and the good heart,” Dharamsala (Library of Tibetan works), 1976.]

Over-politicised, over-conceptualised and media defined, this ‘high modernity’ is the first time that most of mankind is trapped within a bubble that is the present; cut away almost completely from all traces of history and tradition that brought him up to the 21st century. The past and nature with its familiar and comforting signs and symbols are being obliterated fast. Sheltered by centuries of religious traditions, our younger generations are now exposed to powerful horizontal influences from the world outside. Parents and teachers – with their ancient taboos and phobias are being left behind. Identity and ethnic grievances against this assault are rife as much as the unlimited opportunities thrown up for the young of this century to craft wholly original and new identities.

The social realm is getting transformed and young lives are integral to this change. But this human being who has been hunter/gatherer for infinitely much longer than farmer, industrial or ICT man has deep emotional needs. (Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari). There is as a result an urgent call that we must focus more intelligently on our everyday life and its subtle, minute and intimate intra-personal and personal encounters. This is the call for emotional intelligence; and it has come just as the Age of Reason, its structures and assumptions are under assault with the advent of what is now referred to as Age of Anger (Pankaj Mishra) or Age of Emotions…

The Europeans, driven by racism, fought two world wars as they transitioned from multi-ethnic empires to mono-ethnic nations states. Those countries they colonised are now in catch-up mode shedding their imported secular legacies in favour of home grown ethnic politics (descending to plain and simple racism every now and then). From the 1970’s our youth were in the vanguard of these processes; and thousands paid with their lives. Their technological uniformity today goes hand in hand with alienation and ideological diversity. The invisible reality is that they occupy different universes whilst sharing the same auditorium.

…addressed with reason

Prof. Worsak, Chapa Bandara and Dr. Wijewardena all seemed to have a common language – the language of reason. It was significant that Bandara captured the sustained engagement of the undergrads in Sinhala, but this common assumption that we are all reasonable animals is one that needs a close review. There is no question about the conclusion of the articles being a clear message to educators to change their teaching style. The ‘flipped classroom’ with its continuous learning cycle is one example. Such ideas have been circulating for a long time. The failure to operationalise them is the rock on which our secondary education reforms have failed at least since the 1990s. The ‘context’ (referred to by Dalai Lama above) which is examination cantered and intensely competitive has made everyone – teachers, parents and students, focus only on ‘what matters.’ There are other reasons that build this disabling context. Two suggestions can be made.

The European colonisers inducted us into Gutenberg’s galaxy – the world of the printed word. And we accepted this as reality. When communities were classified we took this separation seriously. When life was divided into subjects we became obedient specialists. The social and cultural wisdom required to put this jigsaw puzzle together and see the big picture appears to have run dry in the academia with the decline of arts and humanities under the neo-liberal spell. This appears to be one big reason why we continue to miss connections across erected walls to see the big picture. As a nation we have forgotten that it is the invisible reality that controls the visible manifestations outside.

Secondly, our mammoth state education system appears to defy change by its very size. The addiction to top down centralised control gives little space for doing different at all levels. Those who leave the beaten path can get branded as ‘crazy.’ Schumacher in his work ‘Small is beautiful’ points out that big organisations that are effective have small teams which can meet each other and have meaningful discussions. When our youth complete their university education and go to the private sector they are suddenly required to work as a team. But they come out of a pre-school, school and university culture that is generally selfish and individualistic. We may sit in class together but we have not learnt to share and think together. A narrow culture cannot be changed overnight but we can make a start by experimenting with learning circles and giving marks for collaborative skills and team work from a very small age. Of course, this would need convinced and committed teachers. I started above with the logical proposition and worked my way down to the social and emotional levels to show they are inter-connected. This process of questioning and exploring will not normally happen unless we appreciate the limits of reason.

Hegemonic reason

Admittedly, reason has long been our common ground, since the cognitive revolution 60 000 years referred to by Harari. We need to focus here on the more modern nexus between rationality and coloniality.

Animated by the ethic of separation and clinical thinking introduced by print the Enlightenment of the late 17th and 18th centuries (also referred to as the Age of Reason) became the intellectual bedrock for the Europeans to transform their world.

Great dissenters like William Blake stood against this tide. He pointed out that the assumption of some, that reason represented the only valid form of knowledge was a clear reduction of human experience as it left out or marginalised inspiration, emotion, art and religion as valid sources of understanding.

Even in Europe where the Enlightenment was a thoroughly organic process of change, reason having attained ideological pre-eminence became a new form of tyranny. In the colonies they conquered on the other hand reason, self-legitimated by the laws the Europeans framed would sweep all before them before the natives recovered their wits (considerably influenced by the same set of reasons) – almost a century later.

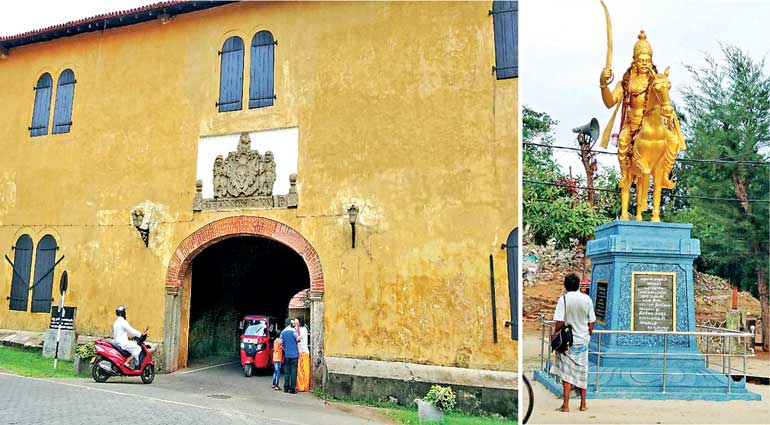

After the fall of Kandy, hegemonic reason decided upon the most fundamental questions that the natives faced while their own identity and traditional social systems were being destroyed.

1.What would be the objective of this new government? The maritime provinces were governed by two private companies (VoC and British East India Company) before the British Crown took over in 1802. By this time the western bourgeoisie were successfully waging its battle for their Governments to accept their objectives, the promotion of private enterprise, as the principal objective. This sea change was extended to colonies.

2.What is the nature of Government? Should it be a monarchy or democracy or something else? The Lankans never deliberated whether their own monarchy should be abolished. The British King was seen as a replacement. Many years later their Western-educated elite would persuade them that we should become a democracy.

3.What would be the form and institutions of Government? The Colebrooke-Cameron Commission would decide this and institutionalise the colony with one master plan. This was a by-pass operation and transplant. We are experiencing different forms of overt and covert rejection by the body politic now.

4.What would be the nature of representation and agency of the people? It was assumed again that the native elite, modelled upon the British elite would seamlessly succeed to the white man’s burden.

Under the middleman

All this produced a stunted and immature society – passive spectators of their own manipulation. They would not really participate in the great questions that concerned them. Instead they would ratify decisions made by others including powerful foreigners. They would be tenants in a house built and owned by others. The native elite did not negotiate freedom in 1948.

What we obtained was an opportunity to decolonise and re-unite as a society. This opportunity we squandered. We retained our fundamental character of coloniality with a set of middlemen in power. They are trustees for freedom and democracy to come. All the imperial lessons we received in democracy, justice and human rights did not become republican roots. They simply bolstered the legitimacy of continued elite rule and their conceptions of power as total, relations as paternal and communication as manipulative of the masses. Public education followed suit. The elite wanted the masses educated – but not too much.

Emotional neglect and poverty continued…

For the Kandyans in particular, the process of colonisation was an emotional disaster. This would be compounded by our collective emotional blindness for the next two centuries and a failure to come to terms with what happened at the human level. Similar patterns would be repeated after the JVP insurgencies and the ethnic war. (Please see Indika Bulankulame’s ‘Frozen Tears’)

The importance of collective healing as a foundation for understanding and learning vital lessons was not prioritised. Our leaders seem disconnected from the cultural capital which made the Truth and Reconciliation Commission possible in South Africa. They continue to pull out impersonal legal solutions for deep-rooted social and emotional problems.

(Read the second part of this article here.)