Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Saturday, 18 November 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

International jurists of the Sri Lanka Monitoring and Accountability Panel (MAP) say the Government has made no credible progress on its transitional justice commitments, and are urging the international community to get tough. This comes as Human Rights Watch also called Wednesday for countries at the UN Human Rights Council to press Sri Lanka on time-bound reforms ensuring justice for serious crimes committed during the civil war that ended in 2009

International jurists of the Sri Lanka Monitoring and Accountability Panel (MAP) say the Government has made no credible progress on its transitional justice commitments, and are urging the international community to get tough. This comes as Human Rights Watch also called Wednesday for countries at the UN Human Rights Council to press Sri Lanka on time-bound reforms ensuring justice for serious crimes committed during the civil war that ended in 2009

By Julia Crawford

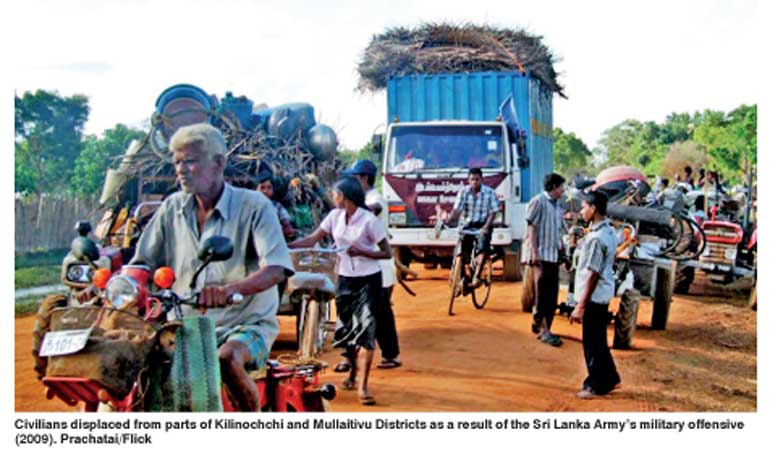

JusticeInfo.Net: The war, which pitted majority Buddhist Sinhalese of the south against minority Hindu Tamils of the north and east, left at least 40,000 people dead, 280,000 displaced and 65,000 disappeared. President Maithripala Sirisena’s Government made key pledges on justice reform at the UN Human Rights Council in October 2015, in accordance with Council Resolution 30/1. It then asked for an additional two years to fulfil them, which was granted in March 2017. But the MAP report says the Government is acting in bad faith. JusticeInfo spoke to US and UK-educated international lawyer Richard Rogers, Secretary and panel member of MAP.

Q: Your report says the Sri Lankan Government has failed to make credible progress on its transitional justice commitments. Why do you say that?

A: The Resolution has four pillars -- an Office of Missing Persons, reparations, a truth commission and a special criminal court. The Sri Lankan Government has only made some progress on one of those pillars, and practically nothing on the others. It has established an Office of Missing Persons, but even that is not functioning as it was envisaged. It lacks independence, and there is clearly a great deal of distrust amongst the Tamil community. So I think there have been no practical steps taken by the Government that can bring redress to the victims of the war that ended in 2009. Not only that, but there have been further human rights abuses committed by Government actors. There have been reports of more people disappearing, of more people being tortured, and there are still many people in detention facing either no justice at all or unfair systems of justice, for example under the Prevention of Terrorism Act. So not only is the situation not being dealt with, but the number of human rights violations is increasing every week.

Q: You say that since justice in Sri Lankan courts looks increasingly unlikely, the international community should act. What are the MAP’s specific recommendations?

A: What we are recommending is that alternative forms of justice should be pursued, as an end in themselves but also as a means of putting extra pressure on the Government to do something back home in Sri Lanka. We are suggesting the pursuit of cases outside Sri Lanka under the principle of universal jurisdiction, to try human rights offenders in third countries. That was a recommendation of the UN Human Rights Commissioner himself, who was clearly exasperated with the lack of progress on the part of the Sri Lankan Government. Another option is “Magnitsky-style” sanctions. This is the possibility in certain countries to sanction individual human rights abusers using the administrative system in Western countries. For example, a human rights abuser would be banned from the United States, denied a visa, if he was there already he would be thrown out, he would have his financial assets frozen and he would be banned from using the US financial system for his benefit. There is similar legislation in the UK and Canada. These options are particularly interesting for victims and civil society because they do not require the same considerable resources as sometimes required for litigation.

Another option is referral of Sri Lanka to the International Criminal Court. Because Sri Lanka is not a party to the ICC Statute this would require a referral by the UN Security Council, and of course the challenge there is that the five permanent members have a veto, so if China or Russia or the United States chose to veto referral to the ICC; that would be the end of the matter. With the current political situation it is very unlikely that the UN Security Council would refer Sri Lanka to the ICC, but that doesn’t mean it should not. In fact the crimes committed in Sri Lanka were certainly some of the worst this century. There were more than 40,000 people killed just in the last two years of the war and hundreds of thousands of people displaced.

Q: I understand that there is at least one case that has been brought under the principle of universal jurisdiction. Can you tell us about that?

Q: I understand that there is at least one case that has been brought under the principle of universal jurisdiction. Can you tell us about that?

A: There’s one case that has been filed against one of the former military leaders called Jagath Jayasuriya. The case was filed in Brazil and Colombia by a civil society organisation, and they filed it in South America because Mr. Jayasuriya was a Sri Lankan ambassador in that region so he was physically present and resident there. So that case was filed with a request to issue an arrest warrant against him and try him in the courts of Brazil or Colombia, on the basis that the crimes he committed were so serious that they satisfy the legal elements for universal jurisdiction. What happened was that he fled back to Sri Lanka just before the case was filed. The belief is that he was tipped off about the case. Of course the Sri Lankan authorities have claimed that he was coming back to Sri Lanka anyway, and they have also denied that he was involved in any of the crimes. In fact they have consistently denied that any of the military were involved in crimes in Sri Lanka, which frankly is ridiculous because there is so much evidence that they were involved, whether it’s witness testimony or video evidence or photographic evidence. There is a mountain of evidence to show that terrible war crimes and crimes against humanity were committed, and there’s a long list of former LTTE (Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam) fighters who surrendered to the Government and have now disappeared.

Q: Following the UN Human Rights Council Resolution and the granting of two more years to the Sri Lankan Government, there will be an interim review early next year. What do you expect to come out of that?

A: I expect nothing to come out of it because what we have seen is the UN Human Rights Council shy away from criticising the Sri Lankan Government or imposing strict deadlines, so I expect it will be more of the same at the next session. What I would like to see is for the Human Rights Council to set a regime whereby they identify steps that must be taken in relation to all four pillars, and they have a monitoring system to ensure that those steps are taken, so that when they revisit the issue after the two years they will be able to say with certainty whether sufficient progress is made.