Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Thursday, 16 May 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Anwar A. Khan

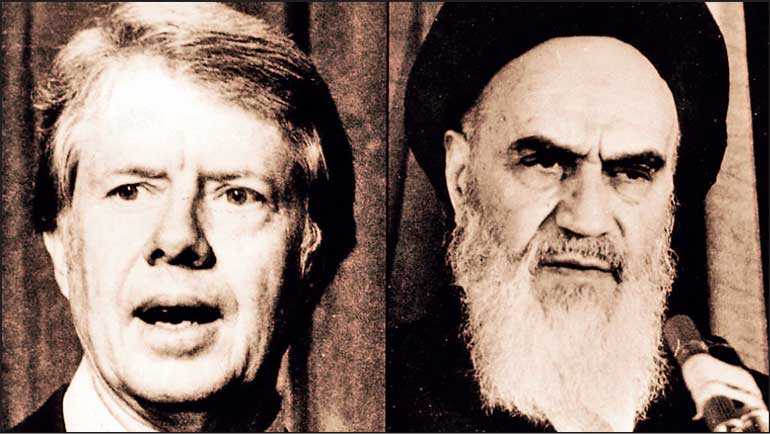

Iranians justified hostage-taking in Tehran 40 years ago on 14 November 1979 ignited a bitter political crisis despite the violation of international law and Islamic principles. The fallout still smites the United States, Iran, and the Middle East. The ultimate loser is now the general people.

What have we learnt about using diplomacy against intense crisis? Not much, if the record with Iraqis, Serbs, Russians… is evidence. Certainly, it is not easy to persuade aggrieved or paranoid opponents to give up assets or activities they deem critical. It takes informed foresight to prepare the ground before a crisis breaks. Sometimes it is necessary to excuse distasteful actions while keeping in mind more distant, larger goals. Sometimes a leader must get tough with an opponent before his public realises a crisis is brewing. Whatever course of action is decided, courage and patience in maintaining it are absolutely critical, but not ignoring the international laws.

10 days after Iranian students seized the US embassy in Tehran and took American diplomats as hostages; US President Jimmy Carter signed an Executive Order freezing Iranian government assets held in the United States. This was the first time a US president used the expansive authorities offered by the 1977 International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), but it was hardly the last example of American economic pressure applied against Iran.

Today, there are eight executive orders active against Iran, each of which begins with a declaration of a national emergency and involves applying sanctions against the country and many of its entities and individuals. These measures, along with sanctions legislation enacted by Congress, are designed to address the full range of US policy issues with Iran, from human rights to missile proliferation to terrorism.

The cumulative effect of the sanctions had a substantial impact on Iran’s economy. Definitive costs are difficult to assess, in no small part because the revolution and resulting chaos had already imposed a heavy toll on the Iranian economy. For example, in 1980, US-Iranian trade plummeted when US exports to Iran dropped from $ 3.7 billion to $ 23 million, while imports from Iran dropped from $ 2.9 billion to $ 458 million – mostly in oil. One case study estimated that the total economic cost on Iran from 1980 to 1981 was roughly $ 3.3 billion.

Suzanne Maloney points out in her book, “Iran’s Political Economy since the Revolution”: “The European reluctance to sanction Tehran over the hostage seizure preserved its traditionally preferential place in the Iranian market and trade remained steady during the early war years, nearly doubling in 1983 with more than $ 6 billion in European exports to Iran.”

The most effective US measure was the asset freeze, which effectively froze $ 12 billion in Iran’s assets, including most of its available foreign exchange reserves,” according to Robert Carswell and Richard J. Davis. Washington took advantage of the fact that, after the turmoil of the revolution, the Iranians were still sorting out how to manage their international financial relations and still maintained substantial reserves banked in the United States. Consequently, Washington was in a position to deliver acute, targeted, and highly disruptive pressure on a key vulnerability at the time.

The exposure to such direct pressure from the United States was a mistake that the revolutionary government sought to correct after sanctions were eventually lifted, with Tehran seeking to hold its reserves much closer to home. But, in the meantime, the cumulative impact of the specific costs imposed by the United States – coupled with the growing financial and diplomatic international pressure to release the hostages – was effective in persuading the Iranians to negotiate.

The hostages were released on 20 January 1981 via the Algiers Accords. The Accords also created an arbitration process, based in The Hague, in which the United States and Iran have negotiated solutions to various commercial disputes arising from the revolution, such as expropriations and cancelled contracts. Most recently, this process awarded a settlement for a pre-revolutionary contract for military equipment – plus interest – that resulted in a $ 1.7 billion transfer to Iran in January 2016.

Three broader results, though, emerged from the crisis that still affects US-Iranian relations and strategy to date. First, the US learnt that Iranian leaders – even in post-revolutionary Iran –remain guided by rational cost-benefit calculations. The revolutionary fervour that Iran’s leaders exploited to consolidate their power over internal rivals in November 1979 helped animate the decision to prolong the crisis.

However, after a year that featured the shah’s death and the invasion of Iran by neighbouring Iraq, Iran’s leaders understood that continuing the crisis posed far more significant risks than benefits. Iran’s leaders did not release the hostages because they changed their view of the United States or lost interest in using the crisis domestically. Rather, Iran’s leaders backed down and sought a negotiated outcome because they decided that it was in their national interest, a fact that encouraged future US policymakers to seek negotiations with Tehran.

In turn, each US president who has sought to use sanctions against Iran has done so with the expectation that Iran’s calculus can be shifted toward more constructive policies. For this reason, US policymakers have viewed sanctions as a useful source of leverage to dissuade Iran’s support for nuclear weapons development. Arguably, this continues to be the case under the Trump administration, which has sought to use sanctions pressure to secure a better deal with Iran than the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) negotiated by President Obama.

Notably, this consensus is challenged by a substantial group of dissenting officials including, prominently, National Security Advisor John Bolton who instead sees Iran as irretrievably hostile to the United States and, consequently less motivated by national interest.

Second, the experience of the hostage crisis demonstrated the advantages and limitations of applying multilateral pressure on Iran. The United States benefited from the cooperation of partners, even if that follow-on pressure was incomplete, sometimes slow, and in some cases more symbolic. Although the main economic pressure came from the United States, the broader sense of growing isolation likely incentivised Iran to cooperate. With important players like the Soviet Union and China defecting, the United States also had to find creative solutions to intensify its own sanctions – a task made harder by the fact that the countries were already less intertwined economically and politically.

This creative application of US sanctions pressure would find full maturity in the secondary sanctions programs of the mid-2000s, in which the United States had little to no economic contact with Iran yet still was able to exert considerable leverage by threatening access to the US economy for those countries still doing business with Iran.

Third, the hostage crisis set the emotional and psychological context among Americans for nearly everything that was to come between the United States and Iran. It made restoring trade and business ties difficult, even if legal, due to the reputational risks (as Conoco discovered in 1995). It also, at times problematically, created a potential analogy for future attempts at transactional diplomacy, as President Obama experienced after the aforementioned $ 1.7 billion debt settlement was conflated with the release of US citizens held in Iran in January 2016. This may be one of the most significant ramifications of the hostage crisis.

The incoming Reagan administration criticised the Algiers Accords as an enormous concession to an act of terrorism. All future US negotiations with Iran would be met with the same accusation, especially wherever sanctions relief was to be applied – this was a critical element of the JCPOA’s reception in Washington.

Such criticism did not stop US administrations from both political parties from contemplating and concluding agreements with Iran involving sanctions relief and debt repayment. In this way, just as the Iran sanctions experience in 1979-81 would teach the United States much about Iranian rationality in foreign affairs, Iran too would come to recognise that it can generate leverage with the United States.

Tehran has characterised its nuclear expansion from 2006-13, for example, as a means of generating leverage for negotiations as well as developing Iran’s nuclear capacity. Iran may likewise see value in regional misbehaviour as a way of not only advancing its security interests, but also creating asymmetric sources of leverage against its adversaries, the United States foremost among them.

In the decades following the 1979 hostage crisis, the United States and Iran have sought to demonstrate a readiness to engage but, also, the limits of engagement. The use of sanctions based on the premise that Tehran remains guided by rational cost-benefit analysis and that even tough unilateral pressure can benefit from multilateral cooperation has been a reliable mechanism for the United States, beginning in 1979 and refined in the years that followed. The question now is whether the limits of sanctions policy have also been incorporated into US strategic thought in order to ensure that they can still be used to guide negotiations.

Trump or American administration still then cannot do whatever they want to the countries across the world at their free-will. Putting these lessons to work might well begin by respectfully talking and listening to Iran. Uncle Sam can’t be the world’s economic police under any settings.

(The writer is a senior citizen of Bangladesh, writes on politics, political and human-centred figures, current and international affairs.)