Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Wednesday, 11 September 2024 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Divya Thotawatte

In Sri Lanka’s male-dominated political landscape, women who dare to enter often face significant challenges. “It is not an easy thing for women to join politics. You hardly see any women taking centre stage,” says Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB) Moratuwa Municipal Council Member Lihini Fernando, who knows first-hand how tough it is for women to gain a toehold on this masculine arena.

Entering politics without prior connections or experience, she faced significant challenges, particularly as a woman competing against a veteran male politician. Lacking access to the tools and knowledge essential to navigate the political system, her journey was demanding. She battled stereotypes that questioned her political role and abilities while juggling the demands of being a mother and wife, challenges her male counterparts seldom faced.

Entering politics without prior connections or experience, she faced significant challenges, particularly as a woman competing against a veteran male politician. Lacking access to the tools and knowledge essential to navigate the political system, her journey was demanding. She battled stereotypes that questioned her political role and abilities while juggling the demands of being a mother and wife, challenges her male counterparts seldom faced.

Fernando’s experiences underscore the grim realities that keep women away from the political arena. The main challenges that kill the political aspirations of women stem from systemic biases that confine them to the domestic space. Societal expectations often pressure women to prioritise domestic responsibilities and the roles of being ‘good mothers’ and ‘dutiful wives’, over political ambitions. Often, economic dependence on male family members, combined with religious and traditional beliefs that view leadership as a male domain also restrict women’s participation in politics.

This leads to their positions, stances and abilities being questioned by voters, donors and political parties alike, resulting in fewer opportunities, resources and funding for them compared to their male counterparts. This lack of funding for their campaigns often ends up in failures, perpetuating a cycle of undermining and failure.

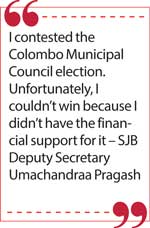

The absence of gender-sensitive policies within political parties further exacerbates this situation. Without structured support or guidelines to address gender disparities, women politicians face additional barriers. The lack of formal gender policies mean there are no clear measures to ensure equitable access to resources and opportunities, reinforcing existing inequalities and making the journeys of women politicians more difficult. The exclusivity of the political space is evident in the consistent underrepresentation of women in Sri Lankan parliamentary elections. According to the Department of Census and Statistics, in 2010, only 6% of the candidates were female (457 out of 7,680 candidates) with just 5.8% getting elected (13 out of 225).

Though the percentage of female candidates increased to 12% (891 out of 7452 candidates) in 2020, their representation in parliament remained stagnant at 5.3% (12 out of 225) members. Meanwhile, men, who comprised 88% of the candidates went on to secure 94.7% of the seats. These numbers highlight how despite the rise in female candidacy, women’s representation in parliament continues to be disappointingly low.

This rise in female candidacy in recent elections is largely due to the 25% quota for women’s political representation in local government, implemented in 2018 through the 2016 Local Authorities Act after 25 years of advocacy. First proposed in the 1993 Women’s Charter, this quota aligns with international commitments like the 1995 Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action. Women’s rights organisations have played a crucial role in this long struggle, highlighting the need for women’s voices in governance and decision-making.

But as Fernando, an attorney-at-law and activist who joined politics in 2018 with the introduction of the 25% quota explains, there was a lot of resistance from men when the system was introduced. “They were asking questions like, ‘Can women actually do politics?’, ‘Why do they need to do this?’, and declaring ‘Women should stay at home, look after children, while we men do politics’,” she recalls.

Despite overcoming the initial resistance to the quota, Fernando observes that entering politics has continued to be particularly challenging for women due to the gender biases they face.

Despite overcoming the initial resistance to the quota, Fernando observes that entering politics has continued to be particularly challenging for women due to the gender biases they face.

She notes that the path to entering politics is shaped by various factors, and for women, it often depends heavily on nepotism. Without strong political connections, most women struggle to gain backing, even from their own parties, as they are frequently written off due to prevailing stereotypes, discrimination, and restrictive gender roles, she says, adding, “There are gender stereotypes and you have to fight them if you are coming forward. Politics is not a level playing field.”

The 2024 report by The International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES) titled ‘An assessment of Women’s Political Representation through the 25% Quota in Sri Lanka: Impact and Lessons Learnt’ highlights these challenges, noting that women remain disadvantaged by misogynistic party structures, and that as political parties operate with immunity—violating democratic principles and lacking financial transparency—there is always a risk that any progressive reform could be undermined.

According to the report, this reality is made more challenging by the party’s ingrained political culture, which ultimately determines how policies are implemented and how resources and support are allocated to female candidates.

The IFES report finds that while male politicians may also face challenges in securing budgetary support for their campaigns, many still receive backing from local leaders through patronage networks, such as family or business connections. These networks are far more accessible to men than women. Additionally, even when women are part of these networks, they often find themselves overlooked in favour of male members.

Financial hurdles for women

The financial barriers exacerbate the challenges women face in politics, making it even harder for them to compete on equal footing with their male counterparts.

Politics is not cheap in Sri Lanka. Fernando explains that running for local government and provincial council may cost around Rs. 1– 2 million—amounts that some can manage. However, running for parliament requires anything from Rs. 15 to 100 million. Given the gender disparities in politics and additional challenges like wage gaps, these financial burdens are often beyond the reach of most women, including Fernando.

A lawyer by profession with strong family support, Fernando spent less than Rs. 1 million on her 2018 campaign for local government, which posed little challenge for her. However, running for parliament would have been a different story.

The substantial amount of funds required are primarily due to the high costs of reaching voters. Candidates must invest in various forms of media to increase their visibility, including television advertisements, billboards and online campaigns.

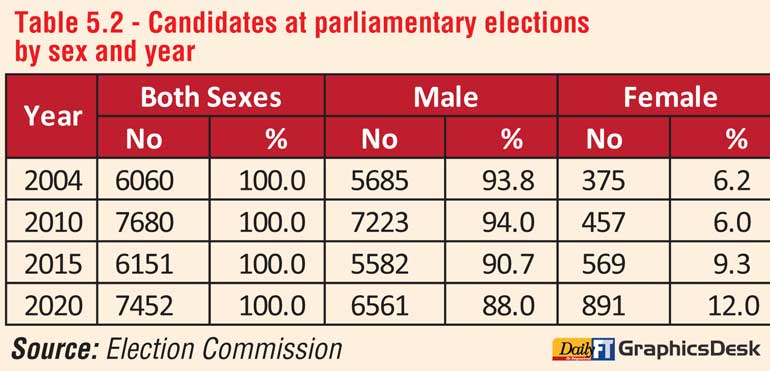

Additionally, funds are required for campaign events, including meetings, providing food and lodging for the campaign team, and sometimes covering significant transport costs. This is especially true for SJB Deputy Secretary Umachandraa Pragash, whose work spans multiple districts.

Pragash, who also entered politics with the introduction of the 25% quota in 2018, found the financial burdens beyond her reach as well. “I contested the Colombo Municipal Council election. Unfortunately, I couldn’t win because I didn’t have the financial support for it,” she says, adding that she had less than Rs. 500,000 to spend on the campaign.

Pragash, who ran as a Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) candidate before joining the SJB in 2020, says she received no funding or sponsorship from the Party, though senior male politicians had received the necessary backing.

“Party funding was unpredictable. We had newly stepped into politics, especially women,” she says, adding, “We actually don’t know about the real situation. Sometimes, senior members and organisers would get funds.”

Working with SJB, she has more backing for her work, yet she still has to personally handle the financial requirements for her campaigns. Her next campaign was in 2020 where she ran with SJB for Parliament in two districts: Jaffna and Kilinochchi. She spent just around Rs. 5 million, largely raised through support from friends and contacts abroad.

Working with SJB, she has more backing for her work, yet she still has to personally handle the financial requirements for her campaigns. Her next campaign was in 2020 where she ran with SJB for Parliament in two districts: Jaffna and Kilinochchi. She spent just around Rs. 5 million, largely raised through support from friends and contacts abroad.

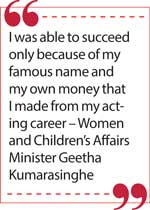

Pragash’s situation mirrors the experience of the Minister of Women and Children’s Affairs, Geetha Kumarasinghe, from the Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP), who has also faced a lack of financial backing throughout her decade-long political career, highlighting a persistent issue with availability or allocation of resources for women politicians. Even if there were any party policies or resources to support women politicians, they were not implemented or spoken about, she notes.

As a former actress without any prior political connection, Kumarasinghe had to fund her campaigns entirely on her own. “It was extremely difficult, and I was able to succeed only because of my famous name and my own money that I made from my acting career,” she says. However, she was unable to offer even a rough estimate of her campaign expenses, as she had not maintained a formal record.

In contrast, some male politicians have access to considerably more resources. According to the Meta Ad Library Report, SJB Leader Sajith Premadasa, SLFP MP for Jaffna and Deputy Chairman of Committees of Sri Lanka, Angajan Ramanathan, and SJB Candidate Kanishka Senanayake spent more than $ 20,000 (Rs. 5.99 million), $ 14,400 (Rs. 4.3 million) and $ 14,100 (Rs. 4.2 million), respectively, on just Facebook advertising during the 2020 parliamentary elections. Such substantial sums, spent solely on social media promotion, highlight the stark differences in campaign funding between male and female candidates.

Lack of supportive party policies

Compared to the other parties, the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP), and the National People’s Power (NPP) the alliance it heads, functions differently, operating a central fund that supports candidates more uniformly. NPP MP Harini Amarasuriya states the campaigns are more party-centred and managed by the central fund so that candidates are not required to raise their own funds.

She elaborates that instead of distributing funds to individual candidates, the party organises and finances their campaigns directly from this fund.

Amarasuriya acknowledges gender-based discrimination exists among male members in every party, but emphasises that NPP attempts to focus on equality for all candidates within the party.

Still, the lack of comprehensive gender policies across the political spectrum remains a significant barrier for women– a common issue prevalent across almost all political parties in Sri Lanka.

This issue is brought out by former Justice Minister and presidential aspirant Wijeyadasa Rajapakshe, who speaking on behalf of SLFP, says that there are no official party policies in place yet to financially support or empower women candidates. However, given the historically low participation of women in politics, Rajapakshe assures that an official party policy to nominate at least 30% women candidates for parliamentary elections is set to be implemented moving forward.

Sri Lanka Muslim Congress (SLMC) Leader and MP Rauff Hakeem, while noting that all candidates need to fund their own campaigns, also admits there are no specific party policies in place to support women candidates or address gender discrimination in Sri Lankan politics. He notes that while the party encourages women to contest with them, their participation remains lower than expected due to the challenging nature of politics in the country. “We try to build up a supporting network around them to see that they are able to conduct the campaign while facing these challenges.”

Though the Ilankai Tamil Arasu Kachchi (ITAK) has no policies that support women members or provide them with resources, ITAK MP for Batticaloa Shanakiyan Rasamanickam, says party nominations have been open to candidates who meet the party’s values and standards, regardless of gender. However, during the last parliamentary election, all eight candidates who contested from the party had been men.

“In a district where there are around 480,000 voters, we couldn’t find a single female candidate,” he says, noting that although two women sought nomination, they did not meet the party’s criteria such as aligning with its policies, ideology and active participation.

Despite their progressive rhetoric, the majority of political parties lack targeted policies that address the challenges faced by women candidates or guarantee them equal opportunities.

“At the local level, there’s enough competent women doing social work, welfare work, and various kinds of public activity. So political parties really can’t say that there aren’t women able to get into politics. The barrier that keeps them away is that they don’t have sufficient social capital and economic capital. They are not networked,” says activist and Women and Media Collective (WMC) Joint Coordinator Kumudini Samuel.

Her words underscore the need for effective support that grants women access to the exclusive political spaces and circles that traditionally offer opportunities and financial backing, typically reserved for male members.

Donors and sponsorships

Rasamanickam says that candidates from ITAK also had difficulties getting donors and raising funds for campaigns as the party did not join the Cabinet. “In our party, even male candidates struggle, unless you have your own source of income,” he says, highlighting how donors preferred to fund candidates who could climb the political ladder.

Six years after their entry into politics, Fernando and Pragash have established their names in the field, but getting sponsorships without exploitation is still impossible. Fernando notes, “You need a massive amount of finances. So women struggle because they have to find donors … (but) they, the donors want something in return. (It) is also one of the factors that stops women from coming into politics.”

Inclusivity and safety within parties

As a woman politician representing a minority/Tamil community, Pragash has faced many difficulties. But both SLFP and SJB created a welcoming environment, she says, explaining that minority women had more opportunities within mainstream political parties because, while gender-based discrimination may exist in all parties, most mainstream parties have policies that provide space for minority women. Both SLFP and SJB confirm this statement.

However, most political parties in Sri Lanka, like ITAK and SLMC, do not have policies that support or are inclusive of other marginalised communities, like the LGBTQ+ community. While the NPP has backed the proposed same-sex decriminalisation law, and Rajapakshe’s manifesto includes measures that are supportive of marginalised communities, there is still a significant gap in ensuring true inclusivity across the political spectrum.

Recommendations

Addressing the imbalance of privileges and disparities of funding granted is essential for a fair electoral campaign.

Hakeem assures SLMC’s support network would assist women candidates facing financial challenges, while Rasamanickam says the ITAK is working towards a more open and non-discriminatory nomination process.

SLFP’s plan to nominate at least 30% candidates for future parliamentary elections, as noted by Rajapakshe, is a promising move towards greater gender parity in politics. Additionally, the SJB MP for Kegalle also states that the party aims to always have more women candidates than is legally required while supporting them with equal opportunities within the party. Drawing from successful international models, Rwanda’s approach to gender parity offers a compelling case. Since implementing a constitutional quota system in 2003, Rwanda has mandated that women hold at least 30% of parliamentary seats. This policy has led to over 60% female representation in the Rwandan Parliament, demonstrating how effective quotas and comprehensive support mechanisms can drive significant change. Rwanda’s success is attributed to its strong legal framework, enforcement of quotas, and dedicated financial and training support for women candidates.

Moreover, in addition to working on official party policies focused on inclusivity and equitable resource distribution, effective financial oversight is crucial. “You need laws for the monitoring of expenses. You need disclosure. There is a whole range of things that the Election Commission hasn’t still been able to put into place effectively,” says Samuel.

She advocates for creating a women’s fund as an effective strategy to help women of all parties. “If there is a ceiling and then you create a fund and all candidates are given an equal amount of money from political parties, then yes. That is something we should be striving for,” she explains.

Despite the challenges, there is hope. Initiatives like the 25% quota at the local authorities’ level and the gradual rise of influential women politicians show that change is possible. To accelerate this progress, political parties must implement policies providing financial and structural support for women candidates, and civil society must more persistently advocate for transparency and equitable funding. Embracing these changes will help create a political environment where women are empowered to lead and make a difference.