Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Friday, 3 January 2025 00:28 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Without employing effective negotiations, the act of passing blame between policymakers and implementers will only exacerbate these games

Policy and bureaucracies

Policy and bureaucracies

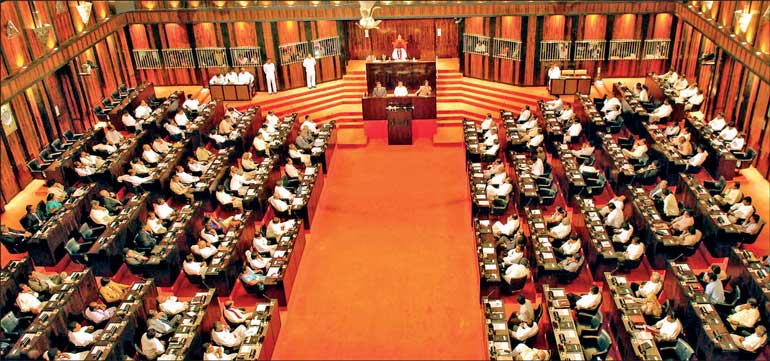

Not surprisingly, civilians place a lot of faith in the government to improve their living conditions. These expectations encompass multiple aspects, ranging from basic needs to more luxurious desires for a better life. Governments have, of course, played a major role in the development journeys of countries that have already achieved advanced economic status, and that role will be critical for economies aiming to follow their path. We often hear grand promises from politicians on stages and various political platforms. These promises are often well-articulated and compelling enough to create visions of a luxurious future in the minds of voters. Unfortunately, the pleasure of most of such dreams is, in most circumstances, limited to the imagination.

Therefore, it is important to understand the process of how those promises can deliver their expectations. Once they are elected, those promises should be converted to policies of the government. And then, they should be implemented as mentioned in the policy documents. Based on the implementation analysis of various countries across the world, policy analysts believe that the implementation stage is more challenging than their formulations (Pressman & Wildavsky, 1984).

Successful implementation should be viewed as a negotiation between politicians and the bureaucracies in the public sector. When policies go to government offices, they could get stuck in their hand due to various unintended causes. According to Eugene Bardach (1977), some such incidents can be understood as games played by bureaucracies that exist in government institutions. We believe that understanding these games is crucial to ensuring that policies achieve their intended outcomes in Sri Lanka.

The Tokenism Game

The Tokenism Game refers to a strategy employed by implementers to give the appearance of compliance or progress while minimising actual dedication towards the initiative. This game often arises when those responsible for implementing a policy aim to please higher authorities and the public without fully committing to the intended goals of the policy.

This can lead to a situation that “looks good but does little.” This game is all about doing the bare minimum to make it look like progress is happening. Officials take small, symbolic actions, like launching a pilot project or publishing a glossy report, a media press, but avoid real work that could implement the policy. When this game is played, bureaucrats introduce programs or make public announcements to show they are working, but these actions do not address the root issues. It is like painting over a cracked wall without fixing the cracks underneath.

In Sri Lanka, some government institutions often appear in the media due to various bribery and corruption practices of their officials. Those incidents also reveal various innovative strategies used by the parties involved in these practices. Anyone can understand the severity of the issues by looking at those stories. In our view, this is a highly possible area to play the tokenism game in practice. For instance, theoretically, ICT-enabled systems should make the lives of the users easy. But in reality, those projects can be implemented without making the lives of the users much different.

The Territory Game

Territory Game refers to the tendency of individuals or groups involved in policy implementation to prioritise protecting their domains. These may include authority, resources, or control over the project activities. This game often involves competition or conflict among government institutions and departments over control, ownership, and resources.

This game is visible when departments focus on their individual priorities instead of working with the holistic picture of the broader policy. This can cause troubles for policy implementation in two ways. First, some public institutions may refuse to share responsibilities because they want to protect their own territory. Second, some institutions responsible for policy implementation may lose the ability to control some areas of the policy simply because it is beyond their territory. Ultimately, these practicalities can have huge impacts on the overall policy objectives.

In Sri Lanka, even though it is small in geographical area, the public administrative mechanism is highly complicated with various institutions at multiple levels. For instance, some schools are under the supervision of provincial councils, while others are overseen by the central government, even though they are located in the same area. This has resulted in a situation where one institution can control only certain schools in the same geographical area. Ultimately, the visibility of the territory game is obvious in these types of institutional setups in the public sector.

The Not Our Problem Game

When it comes to the policy implementation phase, the collaboration of multiple parties is essential, even though it is implemented by one public institution. Some parties tend to play the Not Our Problem Game at this stage of the implementation. It can happen when a department or public institution refuses to take responsibility for an issue, saying, “That is not our job or not our responsibility.” According to policy analysts, problems that need cooperation from multiple agencies often get ignored because no one wants to take charge of certain parts of the task. This leads to a situation where policies get stuck and unsuccessful because no single office feels accountable. These behaviours create a situation similar to a relay race where no one wants to take the baton.

In Sri Lankan history, many such incidents have taken place. For instance, when the Meethotamulla garbage dump collapsed in 2017, it was revealed a series of missteps and failures to act decisively despite long-standing warnings about the dangers posed by unmanaged solid waste.

In Sri Lankan history, many such incidents have taken place. For instance, when the Meethotamulla garbage dump collapsed in 2017, it was revealed a series of missteps and failures to act decisively despite long-standing warnings about the dangers posed by unmanaged solid waste.

Why these issues are unintentional

It is also important to understand the unintentional nature of these games. These games are played due to some unique features of bureaucratic organisations. In other words, these parties often do not intend to undermine the overall policy but act to protect their territory, avoid risks, and ultimately avoid blame from external parties. This highlights the importance of close negotiations between the policy formulators and the implementers to realise the ultimate policy objectives. For example, there may arise the requirement to appoint a central unit with proper authority to solve practical issues arising due to above mentioned games during the implementation. In our view, without employing effective negotiations, the act of passing blame between policymakers and implementers will only exacerbate these games.

(Dhananjaya Madusanka Dissanayaka is a Senior Lecturer, Department of Public Administration, University of Sri Jayewardenepura, and is currently reading for the Ph.D. in Governance and Development, GSPA, NIDA, Thailand. He can be reached via email: [email protected].)

(Charuka S. Walpola is an Assistant Lecturer, Department of Public Administration, University of Sri Jayewardenepura, and she can be reached via email: [email protected].)