Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Saturday, 18 May 2024 00:07 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Who among those associated in an era of violence, values peace, the most; it is those who are immersed in it

The peace of a nation does not lie on the pulpit of the United Nations or any other international body. The long-term stability and sustainability of a country which has paid the price in blood for peace can only come, when like Japan, one revitalises the entire nation, in every sphere, from education to recreation, to sharpen a mind towards a peaceful and holistic mindset. One that is devoid of Mohaya (which can be interpreted as false pride or illusion) or Dweshaya (anger/spite). Such a nation will not have to face the consequences of these base qualities which is Dukkha

(sorrow)

By Frances Bulathsinghala

Within the scriptorium of time that man has written his little legacies, what has been the winning lexicography?

And in the biography of collective human history, where can we find the first embryo of unrest?

How do we quantify the value of wisdom in policy making?

What is the worth of a limb or a life?

How expensive is the memory of what could have been?

Of all those associated in an era of violence, who values peace, the most?

Is it those who glorify battle from the sidelines or those who are riddled in its fire?

Walking into a military establishment in the Northern Province some time back with a Sri Lankan born Tamil professional now domiciled in another country who wanted to meet the military commander to discuss some development projects, I was left contemplating the above questions. Having met the above gentleman in an academic related conference I was told he had obtained an appointment with the military to discuss some entrepreneurship initiatives and asked if I could accompany to help him in any language difficulty that may arise as he did not speak Sinhala.

My previous association as a journalist with the State military I limited to the minimum as I preferred to interact more at community level especially on count of my ethnicity. Although I was entrusted with the coverage of the North from the mid-1990s, especially the 2002 peace process, for the Lankan and South Asian English print media, the socio-spiritual worldview I nurtured did not allow me to divide humans into war heroes or militants.

My quest for understanding the humane condition of ‘dukkha’ and the karmic continuum of life energy beyond death, time and space, prevented me confining myself to either of the above labelling which in a rational sense is what journalistic unbiased comprehending of facts and the subsequent due diligence based objective reporting or analysis is about.

Thus when I walked into the premises of the commanding officer of the former conflict charred territory, accompanying this Tamil philanthropist, I kept an open mind as I did when collecting post-2009 peacebuilding centric research interviews from military personnel as well as former militants and Tamil, Muslim and Sinhala expatriates as a peacebuilding focused scholar/researcher. Much of these case studies, analysis and conclusions have been published in the mainstream English media in Sri Lanka and internationally as well as published in research journals over the years. Thus, as both a journalist and integrated peacebuilding and spirituality researcher, I was convinced that it is men/women who were on the battle ground who valued non-violence the most. A majority of them had honed a keen sense of humanistic perspective as well as discipline of mind and immunity to petty rhetoric. This is contrary to some polarised and populist views, often within the local and international peacebuilding circuit itself, that consign the men of the military or the militants into some generic damnation beyond redemption.

“We have to think what the skill of a man such as Prabhakaran and the others who joined him as fighters could have been utilised for, if the circumstances were different and in a different reality,” opined the commanding officer we met. His individual comment was voiced voluntarily at the end of a three-hour meeting discussing viable entrepreneurship options for the North.

Testing the expanse of his mind, I decide to broach a topic one does not generally raise with the military; i.e. the post-2009 need for strategised de-militarisation from the North and restoration of all land and business opportunities of the region fully to civilians.

His prompt answer was that for long term trust-building this is a dire need, but cited concern for national security. Demilitarisation is a serious topic and has to be understood clearly and pragmatically, looking into previous consultative reports submitted on it. This merits an exhaustive discussion but trust building is a key component of a peacetime potential and if carried out wisely utilising the military skills towards uplifting a nation, the monies that go into sustaining North military establishments could be strategised for truly productive use. This in no sense should mean that national security, which is needed in all parts of a nation, representing the safety of all citizens, should be abandoned. Four years back this writer featured case studies in the mainstream English media of how former Tamil Tiger cadres who had surrendered in 2009 and thereafter been part of State administered rehabilitation program, were instrumental in keeping the peace.

Reconciliation should be a lived-in word

Reconciliation should be a lived-in word. It has to be born and nourished within the hearts of people. Whether reconciliation is in fact the correct word to be used in the Sri Lankan context should also be asked as did one of the current Sri Lankan pillars of northern development Jekhan Aruliah, in an interview published last Saturday in this newspaper.

Indeed, what are the masses asked to be reconciled with? Is it the memory of being trapped for over thirty years in a conflict situation they had no direct hand in initiating? Or is it the fact that the origin of unrest that creates wars are often inflamed by a small percentage of the population but gets presented in a stereotyped fashion tarring one entire community?

In terms of the personal narrative of the above mentioned Sri Lankan origin Tamil gentleman, it is his second visit to an army compound. The first instance was some four decades ago and distinctly unpleasant.

“Actually, I asked you to come with me not just for language based assistance. I was pretty nervous as the first time I was in a place like this it was in a different scenario altogether,” he revealed as we climbed up the stairs of the military building.

It had been in the mid-1980s at the beginning of the Tamil militancy taking up the cause of a separate North-Eastern state. Bombs would shoot out from the earth and there would be no one to own it. The Government military, still unused at the time in how to handle this new phase the nation was plunged in, resorted to rounding up every youth in the vicinity. The pronounced language gap complicates matters more.

In reading recollections of those who have had similar experiences as this gentlemen and sensationally published internationally, at times with particular lobbying agendas that may not really advance the requirement of sustainable healing, one has to ask ‘how would I behaved in a situation like this in the 1980s in Sri Lanka?.” How would I have felt if I was a young Tamil man trapped in this situation? If I was a militant, then what were my reasons for giving up the future I had planned and becoming that? If I was a military person, how would I have felt to not know how many steps I could take before the earth exploded from nowhere and then not know who did it and how to handle the situation?

From the State perspective, especially from one that functions or should function with and within Buddhistic principles, great merit could have been accrued if the skills of judgement and discernment prescribed as part of this doctrine were used. Perhaps the stringent practices such as Ana Pana Sathi, Vipassana and Samatha meditation could have served as major tools for the military to build up their intuition and discernment so direly needed in times of mayhem. This would have helped them make key decisions in deciding who was innocent of carrying out violence and who was not.

For example, the conclusion of many peace and conflict based surveys across the world on the global use of torture in interrogation, show that it serves only one purpose; help in victimising the innocent and not the culprits. Thereby it merely fosters recruitment of organisations carrying out terror based acts worsening conflict situations.

Vellupillai Prabhakaran, like Adolf Hitler arose from the varying circumstances that engulfed two differing geographical locations. Both men had exceptional skill. What they did was based on strong convictions and rigid stereo typing.

Yet, would it be naïve to presume that there could have been an artist of an alternate chiaroscuro in Hitler, had he been enrolled in the art academy he built his hopes on as a youth?

Would it be logical to presume that a man who rose from a fishing community to lead thousands of men into an ingeniously carved out deathly battle taking on an entire government, could have used his leadership mettle differently if post-independence based policies (such as those pertaining to language, for example) were different.

And would we have lived out the history we did if the library of Jaffna were not burnt by politicking rascals and if the 1983 mob violence were prevented at the very onset.

History teaches only those who want to learn

History teaches only those who want to learn. Hence we must never forget that the man who joined the LTTE as its police chief was once a constable in the Sri Lankan police in Narahenpita with a Sinhala wife. A Sri Lankan Tamil policeman who found that even his uniform did not fully protect him from the few strategic lunatics on rampage who plunged the country into chaos from that point and made it seem that the entire Sinhalese population were out to vanquish the Tamils.

What does it mean to write these juxtaposing and rather paradoxical sides of a malady that robbed the nation of its open economy based capacity for prosperity?

What does it mean to read such countering viewpoints? The human mind is a strange device. It gets latched onto labelling opinion quite fast and it is to be understood that an abstract mind who reads only segments of what is defined here may react prematurely, whenever the military and the LTTE is mentioned.

This article was started off by asking some rudimentary questions.

Let us seek to answer them.

The winning lexicography of history can only be with ideology that uses past experience of bloodshed for a national commemoration of peace. Japan is a case in point for preventing the glorification of war, having suffered the horror of the atomic bomb.

The first embryo of unrest in a multi ethnic society is in a single step that makes a particular community/or communities of a nation feel they are lesser than others based on ethnicity, caste, religion or language. Although we can wring our hands that the British imperialists in Sri Lanka started it all with their divide and rule policy, the fact remains that the British transferred decision making in 1948 to the local leaders here. The options for united ruling by valuing and recognising only the Sri Lankan birth identity, ability and diligence, ignoring all other aspects would have prevented majority-minority hangups this island had been shadowed with. A country belongs to its people and the governing structure of any nation should be vested in the people and decided for by the people. For example the GamSabhas of yesteryear was a governing structure that sprang directly from local need. Yet today we get knotted in wordplay.

Devolution and Federalism are bandied about as if they are separatist pawns on a mired chessboard and used at election time to cost a queen or a king. This is because we have not redeemed these words from the mesh of race based politics.

Value of wisdom in policy making is self-evident

We are yet to start a genuine people centric discourse, for example, on how the Sinhalese villages would benefit from an authentic citizen led administrative structure. One that will ease the tension and responsibility of the central government onto civil leadership across the country so that these administrative systems are not clumsy drainers of revenue as it is now but rather the creative force of generating and maximising the regional income; province by province and village by village. This is what should mean when we discuss the linguistics of autonomy. But autonomy is made to look like some phantom creature; its limbs threatened with being torn asunder into two spheres.

Thus the value of wisdom in policy making is self-evident which will require a great deal of cerebral exertion of the magnitude that Sri Lankan politicians and their lackeys are unused to.

The giving into copying how the neighbours handle their matters is another problem; for example in the singing of the national anthem. Whether a nation sings an anthem that spells loyalty to the country in one language or two or three or four or five is up to that country›s leadership taking into account the practical necessity as per the required emotional intelligence. One need not look over the shoulder and say we are doing so because country x or y is doing it.

The national anthem saga is one minor example being used; and in doing so we can see that it was sung in Tamil in the first Independence Day celebration and is a direct translation from Sinhala to Tamil. This writer was once in the North when the anthem was sung in Sinhala after there was some directive to do so and it was a torment standing there amidst aching hearts. As one Tamil woman bold enough to speak out said, “How can we sing with our hearts when we do not know the language – if we sing in Tamil we know what we are saying and we are singing the anthem for Sri Lanka and not one segmented portion of the country.”

The cost of a limb or a life cannot be quantified just in the same way one cannot measure the pain of a wounded heart. The real skill of any leader is to prevent scenarios that begin with wounding the dignity of citizenship of any person of a nation. This is what Singapore did. It managed to avoid policies that hurt any member of its diverse ethnicities and also succeeded in preventing the influence of communism which may have caused bloodshed and chaos. And walking such a tightrope of empathetic governance while keeping to strict discipline and equity, Singapore began its magical ascension and reaped the reward from third world to first. It is today not beholden to any nation or organisation.

It is free of debt. It does not get advice from others because it need not. It has used basic commonsense in developing an economy that was created focusing on maximising strengths and minimising weaknesses. With none of the natural resources Sri Lanka has, it capitalised on the only major asset it had. It is today a global port; a mecca for world trade.

Memory of what could have been different

As to how expensive the memory of what could have been different is, one has to ask a parent what it is to see one’s child only in their dreams.

Sinhalese or Tamil; a parent remains a parent.

This writer recalls covering the peace process time (2002) commemoration ceremony of the first LTTE suicide cadre Miller carried out by the Tamil Tigers to glorify death even in purported peace time. The mother of Miller gave possibly a well-rehearsed and directed speech extolling ‘the cause’ only to break down in tears four hours later in her home where I interviewed her. I noticed the graduation photos of Miller’s expatriate brother hanging on the wall soon as I entered the house. She admitted that she sent him away for safety and took pride that he was a professional.

(The writer is a Sri Lankan and global citizen who seeks to transcend the limitations of ethnic, national and religious identity. She was a key mainstream journalist covering Sri Lanka’s war and peace scenarios from the 1990s. She is associated with the international peacebuilding/capacity building sector and academia. She is currently focusing on different integrated routes towards a higher spirituality, harmony and prosperity within and between human beings using Intangible Cultural Heritage as one of the channels.)

This leaves us very clear on the answer as to who among those associated in an era of violence, values peace, the most; it is those who are immersed in it, because even the most well brainwashed mind, in one pure moment, would consider that death and ending of life can never be an answer.

As to who glorifies battle, it is evident that it is those who never stepped foot amidst the horror and the lament.

As one Tamil citizen worded it succinctly ‘to applaud and send money for violence while enjoying comfort of another land is akin to buying a ticket to watch another’s death; just as one would watch a horror movie munching popcorn.’

In conclusion let this be said. What was posited in this article was a glimpse of ourselves. It was intended to look at how our past would pave our future, depending on the actions we take.

The peace of a nation does not lie on the pulpit of the United Nations or any other international body. The long-term stability and sustainability of a country which has paid the price in blood for peace can only come, when like Japan, one revitalises the entire nation, in every sphere, from education to recreation, to sharpen a mind towards a peaceful and holistic mindset. One that is devoid of Mohaya (which can be interpreted as false pride or illusion) or Dweshaya (anger/spite). Such a nation will not have to face the consequences of these base qualities which is Dukkha (sorrow).

Why peace processes or sustainable endeavours for long-term strategic peacebuilding do not work across the world is because it avoids encompassing those who really need to be pivotal in the vision for a nation’s harmony. Two of the key stakeholders in this objective is a nation’s military and the former militants.

This writer has spent weeks interviewing (former militants who had completed the mandated State rehabilitated program). In one instance I spent weeks going from house to house and at times living in their humble premises, speaking to those that represented different generations. The jadedness of the elders were contrasted with the exuberance of teenagers whose lives were so different to what their parents underwent at their age. They were preoccupied with taking selfies with me and discussing topics such as fashion, trends and opportunities for higher education.

These narratives have appeared in key publications. There were former cadres whose strict disciplinary training were now utilised to very worthy causes and few of them actually detailed out step by step measures that could be undertaken to make Sri Lanka own its peacetime and take responsibility for it.

As they highlighted what is needed was/is a series of interlinked measures that considers psycho-social healing. As we mark 15 years of the end of the strife that turned houses into debris, handicapped or killed civilians and led children into armed combat we have to acknowledge what was done and what should be done.

We should reiterate and repeat in our minds that we must recognise and respect the need to mourn every single life lost in battle as even a life that was turned to terror was a human life. The best we could do is to wish the continuum of that life force in the samsaric sojourn to be non-harmful and to find rest.

In mentioning what should be given credit, it should be noted that Sri Lanka as a leadership policy post-2009 pardoned around 13,000 LTTE cadres who surrendered in the immediate aftermath of hostilities. Unbiased journalistic writing makes it imperative that we acknowledge this no matter how popular or unpopular the political administration which took this decision at the time was or is.

Having said that, we should note that rehabilitation of mindset after an end of a conflict should not be confined to one set of those involved in the saga.

A military mindset used to war time scenarios has to be systematically rehabilitated. Although there is some rationale that the absence of violence over a long period of time may self-adjust the psyche of the key stakeholders aka the military, a nation serious about preparing the ground for long-term stability should do better than this.

We should also comprehend the fact that military members in an entirety are not criminals unless an individual is proved to have committed an atrocity. This holds true for military linked scenarios in Germany or the United States or Sri Lanka. Even some of the Nazi officials who were very much part of Hitler rule and decision making were released after the Nuremberg trials that took place at the end of World War II – on account of it not being proven that they had a direct hand in the heinous acts of terror – such as burning humans in specialised buildings dedicated to the task, making lampshades out of human skin and starvation.

Hence, Sri Lanka should once and for all, end serving peace and stability on the platters of other nations and seek a genuine plan to ensure this nation does not douse itself with hate, despair and petty superiority.

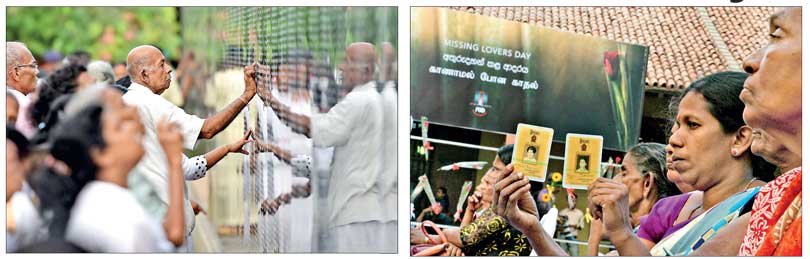

In this 15th year of commemorating 18 May, the day that ended the violence of over 30 years, we as a nation should look at collective mourning. This cannot be emphasised enough. We should mourn the loss of all lives and be done once and for all with the drama and the pomp that goes with separating ourselves into two sides in how we look at an obituary of a past. A past that robbed the nation of its youth and its prime transition as a resplendent nation. Such a nation would have been one where people carried the memory of past Sinhale monarchy who never promoted any kind of ethnic war. This writer has written much about the misconception of the Elara-Dutugemunu war as a ‘Sinhala-Tamil’ war.

The ancient Sinhalese kings knew to recognise human potential and respected the ancient Tamil race that lived side by side upon this land making up the humane tapestry of one of the oldest civilisations in world history.