Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Tuesday, 2 July 2024 00:02 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

GVCs are a reality of modern, globalised production systems

In the late 1970s, during the rising tide of neoliberal globalisation, many countries in the Global South opened up their economies to foreign capital in order to build a so-called export-oriented economy. The ethos that drove such reforms can be divided into two camps:

In the late 1970s, during the rising tide of neoliberal globalisation, many countries in the Global South opened up their economies to foreign capital in order to build a so-called export-oriented economy. The ethos that drove such reforms can be divided into two camps:

In China, pragmatism prevailed, with Chairman Deng Xiaoping stating, “To cross the river, feel for the stones.”

In Sri Lanka, there was an ideological faith in markets and foreign capital, with then President J.R. Jayewardene stating, “Let the robber barons come.”

Today, one of these countries has defaulted on its external debt and is undergoing its 17th IMF program. The other is the world’s factory, contributing to over 35% of global manufacturing value-added and expected to lead the next business cycle. No prizes for guessing which is which.

As Ranil Wickremesinghe continues to administer an IMF reform program for which he has no mandate, he has once again been extolling the virtues of an export-oriented economy. No doubt, Sri Lanka, with its protracted trade deficit, needs to diversify and increase the value-addition of its exports.

However, the question for Wickremesinghe and the civil society hangers-on of the IMF, is whether the current set of reforms have learned from the excesses of Jayewardene’s shock therapy approach to reform. Do these reforms augment Sri Lanka’s productive capabilities and secure her sovereignty in a technologically competitive world?

Productive ecosystems and global value chains

The economist Albert Hirschman famously described development as “the record of how one thing leads to another.” In his theory of general linkages, Hirschman explained how certain economic activities can lead to upstream and downstream spillovers. These linkages can then develop to create a self-expanding local productive ecosystem. But this picture is complicated in an era of global value chains (GVCs).

Since the 1970s, the Fordist ideal of a large, centralised factory bound to a national supply chain has disintegrated. The acceleration of globalisation through improvements in transport and communication technology, and the reduction of tariffs and capital controls, has led to the fragmentation of factories and national economies. Today, capital chases geographies where factor costs are cheapest, establishing resource extraction in one locality, labour-intensive processing in another, and so on. For example, it takes 43 countries across six continents to make an iPhone.

Concomitant with this fragmentation of production is the continued centralisation of capital. According to UNCTAD, 80% of global trade is concentrated within GVCs, particularly through the intra-firm trade of a handful of transnational companies (TNCs). It is estimated that over 50% of the market share in many global industries is dominated by TNCs. In many cases, these TNCs have larger GDPs than some countries in the Global South.

This dialectic of production fragmentation and capital centralisation poses unique challenges for development in the Global South.

Success and failure in global value chains

Only a few countries have managed to leverage GVCs to move from one thing to another. China was for many years considered the example par excellence of a labour-intensive, export-processing economy. Indeed, studies have shown how little value of the final sale of electronic goods accrues to Chinese firms.

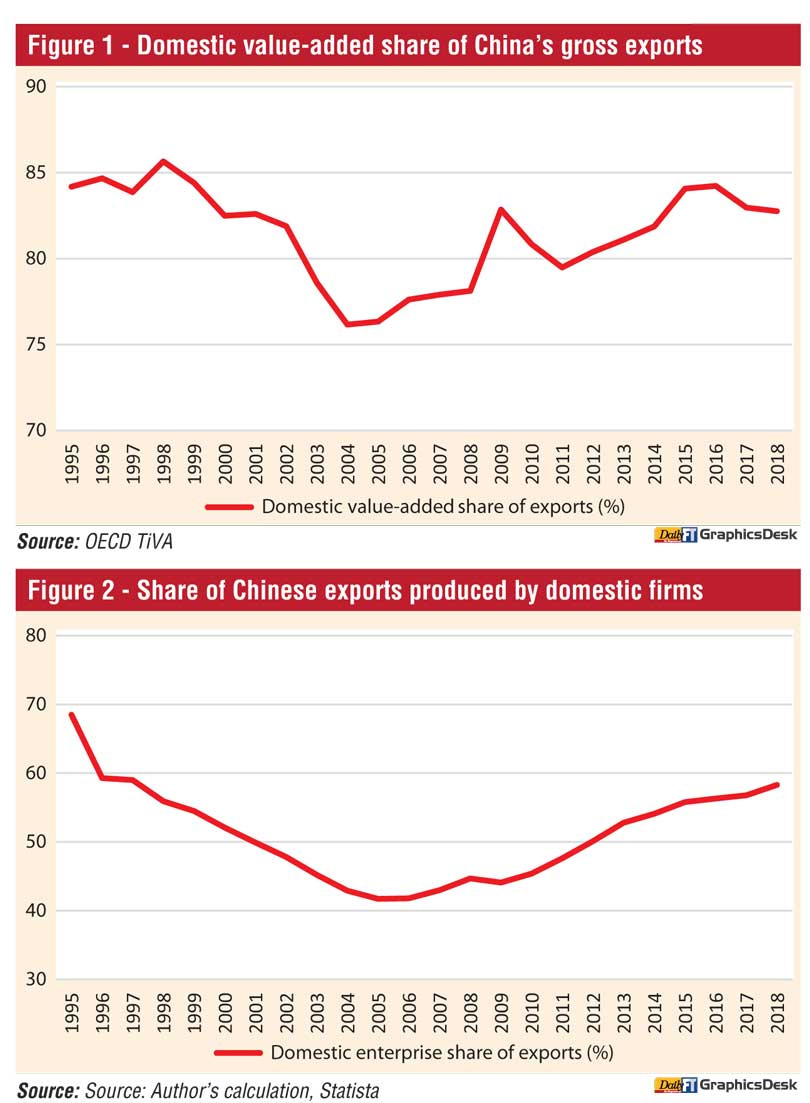

But recent years have seen a gradual expansion in the domestic value-added of Chinese exports (Figure 1). When the iPhone 3G began production in 2008, Chinese firms captured just 3.6% of its final sale value, but by the release of the iPhone X in 2017, Chinese firms were able to capture 25.4% of the product’s value.

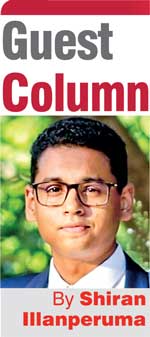

China is an exceptional example of a country that linked up to GVCs, linked back to a local productive ecosystem, and kept pace with global technological change. Today, China is capable of producing technology and brands that outcompete incumbent TNCs, as evidenced by the fact that exports are increasingly driven by domestic firms rather than foreign-invested ones (Figure 2).

Many countries in the Global South have not been able to emulate this success. Sri Lanka opened up to foreign capital at around the same time as China in the late 1970s—Deng Xiaoping even sent a delegation to Sri Lanka to study its Special Economic Zones. Here, trade liberalisation was allowed to kill off infant industries, as policymakers hoped that TNCs would bring with them market access, advanced technology, and better managerial skills.

Export-oriented manufacturing linked to GVCs produced an initial sugar rush of employment and profits, and has since been a mainstay of the economy. However, it has failed to produce a virtuous cycle of reinvestment of profits into expanded productive capacity and new technological frontiers.

In Sri Lanka, 83% of industrial exports are by companies registered with the Board of Investment, most of which are foreign-invested enterprises (FIEs). Domestic value-added remains fairly low, due to the lack of a local supply chain. The export basket is extremely undiversified, with textiles and clothing comprising 35–45% of the total over the last three decades.

For Sri Lanka, one thing has not led to another. On the contrary, the country has become a prime example of premature deindustrialisation.

Surviving global value hierarchies

GVCs may be better understood as global value hierarchies, with each link of the chain representing a certain set of productive capabilities as well as a claim on value. In a closed economy, these links would add up to a local productive ecosystem. But in an open economy, countries risk being locked into a monoculture of productive capabilities at the bottom of the hierarchy.

To avoid this trap, many of the lessons of developmentalist industrial policy can still apply in the era of GVCs. FIEs are unlikely to take the initiative to set up domestic linkages unless compelled to do so. China’s success in GVCs lies in its strategic use of industrial policies to facilitate the transfer of foreign technology and boost its own domestic supply chain. As a result, Tesla’s Gigafactory in Shanghai procures 95% of its components from within China.

Unlike Sri Lanka, China never opted for a shock-therapy approach to reform. China’s home market was well-protected by a state monopoly on foreign currency and imports until the 1990s. Even during the peak of SOE reforms in the 1990s, the slogan was to “grasp the large and let go of the small”. Chinese SOE reform consolidated control over the commanding heights of the economy, enabling it to provision the infrastructure and heavy industries required for export competitiveness. Meanwhile, openness foreign-investment has always been selective and conditional on transfer of technology.

Export orientation and linking up to GVCs can therefore produce two outcomes. The first, in which proactive industrial policies are deployed, can lead to the formation of a local productive ecosystem. The second, in which a “natural path” of development is allowed to proceed, leads to a stagnant monoculture. This, in turn, inhibits the development of productive capabilities and leads to premature deindustrialisation.

Industrial policy, or the art of getting from one thing to another

GVCs are a reality of modern, globalised production systems. Countries like Sri Lanka have little option but to work with or around them. No one today is seriously asking for a “closed economy.” At present, the term is merely a strawman used by market fundamentalist to shut out debate. The task for policymakers today is to push forward domestic actors, not as mere subcontractors in GVCs, but as active, learning agents, and future competitors.

The specific strategies that policymakers can use to capitalise on the opportunities and overcome the challenges of GVCs are context-specific. Larger economies like China and India may be able to leverage access to their home market to force technology transfers. Others, like Vietnam or Mexico, may be able to exploit the relocation of production caused by trade wars. Resource-rich countries, like Indonesia, Angola, or Bolivia, may be able to leverage their market share of critical minerals to induce investment in downstream processing activities.

Finding what works for a country like Sri Lanka is a matter of “feeling for the stones.” What doesn’t work, is to “let the robber barons come” and expect them to develop your productive capabilities for you. It is up to local actors to prioritise the adoption of new technologies, and to develop a local productive ecosystem that can generate its own technologies and national champions.

Sri Lanka’s policy trajectory under the ongoing IMF reform program suggests the country is making the same mistake it made in 1977 and shows scant regard for nurturing the country’s productive capabilities. Despite Ranil Wickremesinghe’s constant lip service over the need for a plan to revive the economy, what we are seeing so far is merely the second coming of the robber barons.

The mindless pursuit of privatisation and free trade agreements as ends in and of themselves speak volumes about Wickremesinghe’s lack of an industrial vision for the country. While Sri Lanka is busy opening casinos, converting post offices into hotels, and relying on the age-old developmental cul-de-sac of “export agriculture,” others across Asia are formulating industrial policies for the 21st century.