Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Monday, 30 September 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Dilani Hirimuthugodage

The Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) is marked by leaps in the digital and technological spheres that enhance human abilities as never before. It includes the internet of things (IoT), block chains, big data, and artificial intelligence (AI), among others.

Unlike the three previous revolutions, during the 4IR, technology and innovations are at an increased risk of falling victim to Intellectual Property (IP) right violations, due to their important role in wealth creation and socio-political stability. As such, the development of comprehensive regulatory systems, inclusive of intellectual property (IP) protection, is crucial in this era.

Currently, Sri Lanka is at a midway point in the 4IR. While the country is familiar with some of the 4IR technologies such as on-line purchasing, e-governance, smart agriculture, smart classrooms, and smart banking, other developments such as IoTs, robotics, and blockchain are still relatively new. This article focuses on how Sri Lanka’s Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) regime could accommodate the changes brought on by the 4IR.

IPRs in the 4IR: The challenge

‘Trade Related Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs) Agreement’ provides the regulatory framework to promote innovation, transfer, and dissemination of technology through IPRs. Mechanisms such as patents, copyrights, trademarks, and trade secrets can be used to protect the ownership of innovations platforming this era.

Patents, in particular, play a pivotal role, as they provide exclusive rights to inventors. However, the patenting of computer-related inventions remains a challenge in the 4IR. Presently, many innovations are based on software and data. Providing protection for intangible assets like software is complicated. It is made more difficult because different elements of software are likely to be developed by different entities in different parts of the world. As such, identifying ownership is more challenging under existing IP systems.

Copyrights are also important to protect creative, artistic work. In the present digital era, a substantial number of software are released on copyright licenses. Moreover, the TRIPS Agreement’s clause on ‘Computer Programmes and Compilations of Data’ specifies that computer programmes could be protected as literacy work under copyrights. However, they only protect the idea and creative aspects and not the software programming language (source code) or the functional behaviour (algorithm) of the software.

In addition, trademarks and trade secrets can also help to protect innovations related to marketing.

In the 4IR, most inventions relate to the IoT, which consists of smart objects and operate autonomously with AI and big data. There is a growing number of inventions that use software to combine information processing and networking, which can be used across diverse platforms. Moreover, big data, which includes ‘data-analysis techniques’ and ‘business models’, plays a major role. However, there is no proper mechanism to gain ownership of data.

Presently, the IPR provides protection for physical objects, devices, structures, physical outputs, physical systems, and physical connections. With the implementation of the 4IR, the focus of protection needs to expand into intangible items such as methodologies, data ownership, configuration of virtual systems, processing algorithms, and brand recognition. Thus, it is challenging for the existing IPR regimes to provide protection for technologies and innovations in the 4IR.

Where does Sri Lanka stand?

In this era, machines can make decisions with very little human intervention. The relationship between humans and machines are also changing. Thus, innovation and creativity drivers, based on traditional engineering technologies, are now reliant on automated, computerised methods.

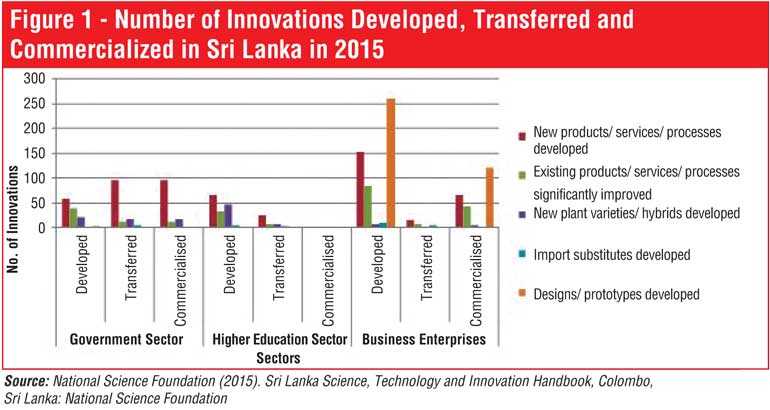

Figure 1 explains the pattern of innovations in Sri Lanka. The number of innovations developed by business enterprises is greater than those engineered by the government sector and the higher education sector. The highest number of innovations emerge through designs and prototypes, new products, services and, process developments. This highlights that Sri Lanka too is moving towards advanced technological innovations. However, the higher education sector has not engaged in any commercialisation activities, while the innovation drive is dry in the government sector. This shows that the country is not only lagging behind in the number of innovations, but also in the transferring and commercialisation of innovations.

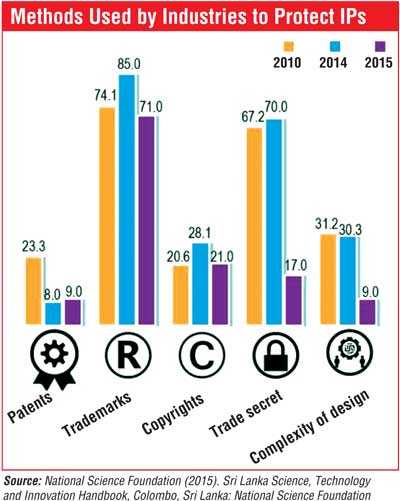

With the implementation of the TRIPs Agreement in 2003, Sri Lanka provides IPR protection to safeguard innovations; the method of protection depends on the type of invention. The graph below indicates that trademarks, copyrights, and trade secrets are the most popular IP protection methods in Sri Lanka.

Modifying Sri Lanka’s IPR regime

Worldwide, steps are taken to strengthen IPR regimes in the digital age. For instance, the European Patent Office (EPO) has issued new guidelines for the patentability of AI and machine learning (ML) inventions. The European Union (EU) has also adopted a ‘sui generis’ system to protect databases. The EPO has invested heavily in recruiting appropriate patent examiners to address the multidisciplinary nature of the 4IR. Moreover, the EU recently implemented the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), especially to protect the processing and transferring of personal data. In Japan, there are guidelines to deal with the authorisation of data utilisation. It has also identified ways to ensure the protection of data during transfer and exchange. In India, the establishment of IP facilitation centres is helping to bridge the gap between practitioners and AI developers, and provides training to IP granting authorities.

To encourage innovation in the 4IR, Sri Lanka must have a robust IP system in place. To effectively use IPRs to stimulate innovations, alternatives such as integrating with regional patenting organisations, sharing information, and fostering conducive relationships with other national patenting offices can be explored. Simultaneously, it is important to create public awareness of IPR services. Especially when it comes to patenting, how patents can support and encourage inventors by providing recognition and rewards, and methods to transfer inventors’ knowledge into tradable assets are valuable.

Furthermore, international best practices suggest that merely being a signatory to TRIPs Agreement is insufficient; the most important step is national enforcement. The implementation of the existing IPR policy and the effective management of IP is crucial. It is also important to provide IPR policy management for research institutes, universities, and other higher education facilities, especially in the areas of commercialisation, research collaboration, and ownership of innovation. Updating the existing IPR regime to address issues arising from new technology applications from the IoT, AIs, and big data is needed. These include means to patent software, protect new plant varieties, and strategies or guidelines to protect big data. Such efforts should be supplemented by capacity building in the form of technically sound IP examiners (especially in patents and trademarks) to explore IP applications based on IoT and AI.

(*This blog is based on a chapter written for the forthcoming ‘Sri-Lanka: State of the Economy 2019’ report on Transforming Sri Lanka’s Economy in the Fourth Industrial Revolution.)

(Dilani Hirimuthugodage is a Research Officer at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS). To talk to the author, email [email protected]. To view this article online and to share your comments, visit the IPS Blog ‘Talking Economics’ – http://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/)