Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Saturday, 14 October 2023 02:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Zheng was also careful about honouring local cultures. In the National Museum in Colombo, visitors can find a tablet he carried all the way from China to the country to pay homage to local religious beliefs. Written in Chinese, Tamil and Arabic, Zheng gave praise to Buddha, Tenavarai-Nayanar, and Allah. He offered

similar lavish tributes to the Gods

By Yi Fan

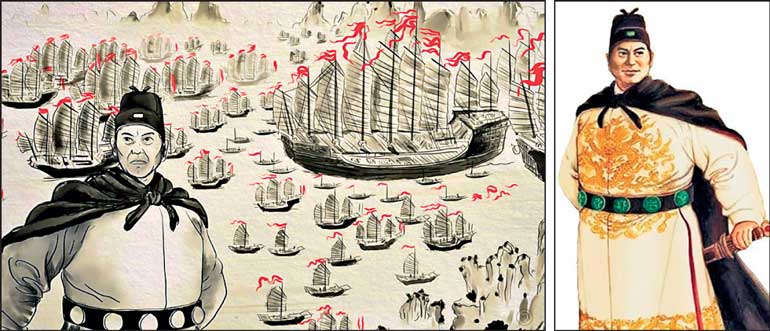

Over 600 years ago, a large fleet containing hundreds of ships from China’s Ming Dynasty traversed the Indian Ocean. The man at the helm was Zheng He, Asia’s famous navigator and explorer whose adventures preceded that of Christopher Columbus by over 80 years. But Zheng’s story is much less recounted in the Eurocentric narrative of history.

Where did Zheng visit?

Historical accounts of Zheng He’s travels record seven voyages to the “Western Oceans,” which at that time referred to Namoli Ocean, later called the Indian Ocean. Setting out from what is modern China’s Fujian Province, Zheng He and his crew made port calls at today’s Java, Palembang, Thailand, Malacca, Sumatra, Sri Lanka, India, Iran and as far as Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. Some historians count more than 30 countries and places in Asia and Africa that Zheng visited between 1405 and 1433.

What was his fleet like?

While scholars are still trying to agree on the exact measurements of Zheng’s ships, historical records suggest that the capital ship could be 61.2 metres long, 13.8 metres wide and of 1,000 tons of displacement. One particular trip was described in more detail. In July 1405, Zheng led a fleet of more than 240 ships with a 27,000-strong crew, among who were marine surveyors, sailors, soldiers, doctors, cooks, translators, astrologists and barbers.

What did he do during those voyages?

Unlike explorers from the European sea powers in the late 15th century who seized territories or tyrannised locals, Zheng He’s mission was mainly one of trade. His ships usually carried goods favoured by the coastal communities, such as, silk, porcelain, herbs, ironware and coins. During port calls, Zheng would first announce his friendly intentions by reading a message from the Ming Emperor and then engage in robust trade with the local people. Things sought by the Ming court included spices, fabrics, gems, rhino horns and animals that were considered exotic by the Chinese.

In addition to trade, Zheng carried out one of the world’s earliest counter-piracy operations. In the early 1400s, Palembang was under the control of a powerful “pirate king” named Chen Zuyi, whose nearly 100 battleships and 10,000 pirates terrorised merchants travelling through the Indian Ocean. Zheng and his “treasure ships” were a prime target. But Zheng had heard all about Chen before entering the waters under his control. Zheng ordered his fleet to be ready for combat. In their exchange of fire, the Chinese navigator managed to destroy Chen’s fleet, kill 5,000 pirates and capture Chen alive. Chen was taken to the Ming capital and executed in the presence of foreign envoys and the public to deter others with similar ambitions. The operation was widely hailed by the coastal communities in southeast Asia.

Zheng was also careful about honouring local cultures. In the National Museum in Colombo, visitors can find a tablet he carried all the way from China to the country to pay homage to local religious beliefs. Written in Chinese, Tamil and Arabic, Zheng gave praise to Buddha, Tenavarai-Nayanar, and Allah. He offered similar lavish tributes to the Gods.

Peace begets peace

As a result of Zheng’s goodwill visits, the coastal kingdoms in southeast Asia developed knowledge of and interest in Ming China. In 1423, over 1,200 envoys from 16 kingdoms in Calicut, Kochi, Cail and Lamuri gathered in Beijing to seek closer ties.

In the “might is right” age when international law or norms were scarce, Zheng’s peaceful trade and cultural missions were a rarity. This was deeply rooted in Ming China’s foreign policy as well as Chinese culture.

The Huang-Ming Zuxun, or Instructions of the Ancestor of the August Ming, the founding emperor of Ming had this warning for his sons and grandsons, “My offspring shall not abuse China’s strength to wage unprovoked wars and take innocent lives.” To ensure lasting peace in China’s neighbourhood, he specifically named 15 neighbouring countries as “states against which Ming shall never use force,” such as those in ancient Korea, Japan, Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, Indonesia, India, Malaysia and Brunei.

The Ming Dynasty’s desire for peace was not out of a lack of strength. For perspective, China in those days had a population of over 100 million and highly advanced industries such as shipbuilding. It was a supersize kingdom. Overpowering the smaller kingdoms across the seas would not have been an impossible or costly task. But Ming chose not to do so and committed itself to peace for generations to come. Domination of other people is not an urge that Chinese culture has to resist, but a foreign concept that has never made its way into the consciousness of the nation.

(The writer is a Beijing-based international affairs commentator.)