Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Thursday, 20 March 2025 00:28 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Criticisms of the IMF’s policy recommendations have largely centred on the damage they inflict on the populations of countries forced to adopt them, particularly on poorer sections of society

|

Introduction

As Sri Lanka’s debt crisis intensified in late 2021, increasingly urgent calls were made for the Government to seek assistance from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Even among the protesters who had taken to the streets to express their opposition to Government policies, some could be seen holding pro-IMF placards. The prevailing sentiment was that only the IMF could prevent the country from descending into total economic and political chaos and, perhaps more importantly, restore it to a sustainable external debt path.

This article questions the objective basis for this widespread trust in the IMF. It is structured in two parts.

Part 1 examines the IMF’s diagnosis of external imbalances in developing countries and its corresponding policy recommendations. It argues that these diagnoses and recommendations have long been recognised as lacking theoretical rigour and empirical support. Indeed, the demand for the IMF’s involvement in resolving debt crises in developing countries is not based on a rational assessment of its analyses and policy prescriptions. Instead, it is typically driven by foreign and domestic business elites who expect the IMF to do what it has consistently done in other developing countries: provide ‘rescue packages’ that ensure the continued servicing of foreign (and domestic) debts while shifting the burden of economic adjustment onto ordinary citizens.

Part 2 focuses on the role the IMF has played in Sri Lanka’s recent debt crisis within this broader context. It argues that the IMF’s diagnosis of the root causes of the crisis, as well as the policy recommendations it put forward to address it, clearly illustrate a fundamental misdiagnosis of such crises. Moreover, it highlights the damaging consequences of IMF policies, which, rather than addressing the structural weaknesses that led to the crisis, often exacerbate economic hardship—particularly for the most vulnerable sections of society and notwithstanding the social safety nets which are a feature of current IMF packages. The likely outcome in Sri Lanka, as in many other developing countries, is yet another foreign exchange crisis. However, in Sri Lanka’s case, this may be further compounded by a domestic debt crisis, deepening the country’s financial instability.

What is the IMF and what does it do?

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) was established alongside the World Bank and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) after World War II by the United States and its key allies, principally the United Kingdom. Its primary purpose at the time was to assist in the reconstruction of war-ravaged Europe and Japan. To achieve this, it initially adopted a ‘Keynesian’ approach to explaining external imbalances and formulating policy advice. According to this perspective, responsibility for external imbalances was attributed to both deficit and surplus countries. Countries running external deficits were criticised for excessive expansions in aggregate demand, while those running surpluses were blamed for failing to expand aggregate demand sufficiently.

By the early 1970s, following the completion of post-war reconstruction in Europe and Japan and in light of the ongoing decolonisation process, a shift began in the IMF’s economic thinking. From this point onwards, responsibility for external imbalances by the institution was placed squarely on deficit countries, with deficits primarily attributed to fiscal policy-induced excesses in aggregate demand. As economic ideology increasingly shifted towards ‘Monetarism’, external imbalances in developing countries came to be blamed on excessive increases in the money supply. These, in turn, were attributed to fiscal deficits financed by central bank money printing, as well as the failure of monetary authorities to allow currency depreciation to offset these imbalances (Stiglitz, 2002).

This shift in economic thinking was accompanied by a corresponding change in the IMF’s policy recommendations for deficit countries. Broadly speaking, these policies were contractionary in nature. They included reductions in budget deficits and restrictions on monetary expansion through money printing, increases in real interest rates, and currency depreciation. Perhaps most significantly, the IMF also advocated foreign commercial borrowing to bridge foreign exchange shortfalls. Over time, these policies became conditions for receiving IMF (and World Bank) loans, embedding them as standard components of structural adjustment programmes (Stiglitz, 2002).

Problems with IMF diagnoses and policy recommendations

The major problems with the IMF’s post-1970 diagnoses of external imbalances in developing countries, and its corresponding policy recommendations, stem from two key issues. Firstly, they rely on the widely criticised quantity theory of money, which has long been discredited in many economic circles. Secondly, even in its modified form, the IMF’s application of the quantity theory is internally inconsistent and illogical.

The fundamental flaws in the quantity theory that underpin the IMF’s approach to external imbalances and policy prescriptions are now being increasingly recognised—not only by central bankers in advanced economies but also by a growing number of academics and even some IMF staff members (Gross and Siebenbrunner, 2019). These criticisms highlight several key points.

First, once it is accepted that central banks implement monetary policy by setting interest rates rather than targeting the cash base of the system to control the money supply (i.e. commercial bank deposits), it becomes clear that changes in the latter cannot be considered exogenous—that is, they are not simply the result of prior adjustments in the cash base. Instead, this critique suggests that changes in the money supply are endogenous to the system, meaning they follow shifts in the quantity and price levels of goods and services in circulation.

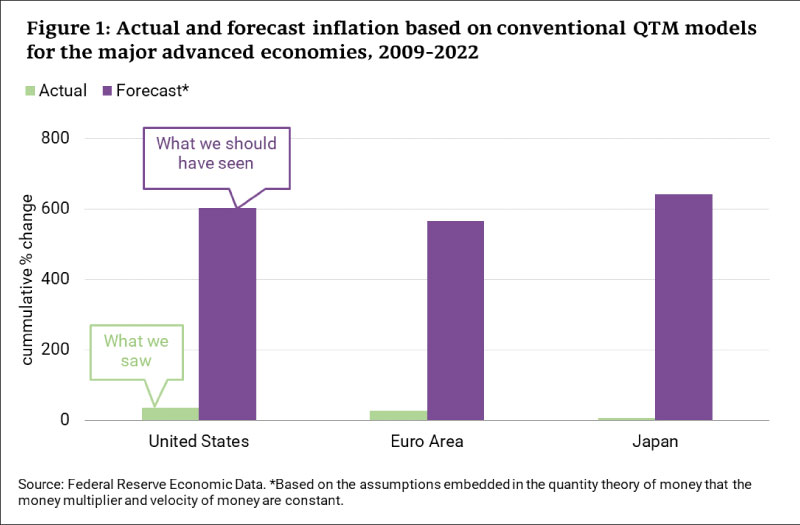

Second, and perhaps most significantly, the extensive quantitative easing (QE) programs implemented by central banks in major advanced economies following the 2008–09 financial crisis failed to produce the inflationary outcomes predicted by quantity theorists. Contrary to expectations, these large-scale monetary expansions did not result in a significant increase in inflation rates. In fact, as Figure 1 shows inflationary pressure in the major economies (US, Europe and Japan) resulting from the QE programmes was only a small fraction of what was predicted by the quantity theory models. Inflationary pressures only emerged later, driven by a sharp rise in energy prices and supply chain disruptions following the COVID-19 lockdowns (from 2022 onwards). This real-world evidence stands in stark contrast to the assumptions of the quantity theory.

The logical inconsistencies in the IMF’s modified version of the quantity theory are equally problematic. The IMF attributes external imbalances to excessive money printing, but it specifically blames the expansion of the money supply resulting from the financing of government budget deficits. What remains unclear—and is rarely, if ever, explained—is why money printing for deficit financing is assumed to be more inflationary than other forms of monetary expansion, such as central bank lending to commercial banks through the repo market.

It is worth noting that recent IMF models have increasingly downplayed—or in some cases, entirely discarded—the direct attribution of external imbalances to the monetary financing of government budget deficits. The precise timing of this shift is difficult to pinpoint, but it becomes evident in IMF external imbalance models from 2013 onwards. For instance, a 2013 IMF staff paper indicates a clear shift in emphasis, with explanations of current account imbalances focusing on changes in aggregate demand—often referred to simply as ‘demand’. While fiscal imbalances continue to play a role in these models, their impact is now framed in terms of their influence on relative aggregate demand rather than as a direct monetary phenomenon (see Philips et al., 2013).

The IMF as a guardian of the global division of labour that benefits the advanced (industrialised) countries

Criticisms of the IMF’s policy recommendations have largely centred on the damage they inflict on the populations of countries forced to adopt them, particularly on poorer sections of society. However, what has received considerably less attention is the fact that these recommendations rarely, if ever, lead to sustainable solutions to the external imbalances and foreign debt problems of developing countries. This explains why so many of these countries repeatedly return to the IMF for further rounds of its destructive economic prescriptions.

That the remedies imposed on developing countries fail to bring about lasting improvements in their external balance and foreign debt problems should come as little surprise once the true role of the IMF and other Bretton Woods institutions is understood. At its core, the IMF exists to maintain a global division of labour (GDL) that serves the interests of advanced economies—namely, the countries that control the IMF.

The GDL refers to the organisation of production on a global scale, where certain countries—what we today call developing countries—are assigned the role of raw material suppliers and low-value-added manufacturers, providing inputs for industries in advanced economies. This structure was firmly established in the later stages of colonisation, when colonial powers forced their territories to produce goods and services, as well as supply slave labour, to meet their own economic needs. Industrialisation in these colonised and militarily weaker nations was actively suppressed through restrictive legislation and the imposition of exploitative treaties (Chang, 2006).

It has long been understood that countries explicitly prevented from pursuing industrialisation eventually hit a foreign exchange crisis. This is because they typically run persistent trade and current account deficits, leaving them reliant on borrowing to secure the foreign exchange reserves needed for solvency. In the post-World War II period, as these countries accumulated unsustainable levels of foreign currency debt, they were inevitably forced to seek assistance from the IMF. While the IMF has generally been willing to provide this support, it does so on the condition that recipient countries implement a series of policies supposedly aimed at restoring economic stability. Many of these policies, however, are deliberately designed to obstruct industrialisation efforts, reinforcing these nations’ assigned roles within the global division of labour as suppliers of raw materials and low-value-added goods.

These IMF-imposed policies typically include trade and financial market liberalisation, the privatisation of public utilities, and an increasing reliance on commercial sources of both domestic and foreign debt. The latter, in particular, places upward pressure on domestic real interest rates and exacerbates currency crises when they occur. The cumulative effect of these measures is to keep developing countries trapped in a cycle of economic dependence, ensuring that their external imbalances remain unresolved.

As argued in Nicholas and Nicholas (forthcoming), it is telling that within the IMF, the term ‘industrial policy’ is met with outright hostility. This attitude towards industrial policy within the organisation is highlighted in an article by two IMF researchers, Cherif and Hasanov (2019), titled “The Return of the Policy That Shall Not Be Named: Principles of Industrial Policy”. Their work underscores the reluctance of the IMF to acknowledge the role of industrial policy in fostering sustainable economic development.

References:

Chang, H-J. (2006) ‘Policy Space in Historical Perspective with Special Reference to Trade and Industrial Policies’, Economic and Political Weekly , Vol. 41, No. 7, pp. 627-633.

Cherif, R., & Hasanov, F. (2019). The return of the policy that shall not be named: Principles of industrial policy. IMF working paper, No. WP/19/74. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Gross, M. & Siebenbrunner, C. (2019) ‘Money Creation in Fiat and Digital Currency Systems’, IMF Working Papers, Washington: IMF, WP/19/285.

Nicholas, H., and Nicholas B. (forthcoming). ‘The bankruptcy of IMF policy recommendations; the recent experience of Sri Lanka’. Sri Lanka Economic Journal.

Nicholas, B. (forthcoming). Rethinking industrialization: Conception, history, strategies and policies. PhD, University of Colombo.

Phillips, S., Catão, L., Ricci, L., Bems, R., Das, M., Di Giovanni, J., Unsal, D. F., Castillo, M., Lee, J., Rodriguez, J., & Vargas, M. (2013). “The External Balance Assessment (EBA) Methodology.” IMF Working Paper No. 13/272.

Stiglitz, J. E. (2002). Globalization and Its Discontents. W.W. Norton & Company.