Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Thursday, 3 April 2025 01:58 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

President Anura Kumara Disanayake

Former President Ranil Wickremesinghe

IMF Sri Lanka Senior Mission Chief Peter Breuer

Introduction

Introduction

In Part 1 we assessed the IMF’s diagnosis of external imbalances in developing countries and its corresponding policy recommendations. We argued that these diagnoses and recommendations lacked theoretical rigour and empirical support. Furthermore, we suggested that the primary reason developing countries accept IMF policy recommendations for resolving balance of payments problems is that they have no viable alternative—particularly given the influence of foreign and domestic elites who lobby for IMF engagement. These elites anticipate that IMF rescue packages will safeguard the servicing of foreign (and domestic) debts while shifting the burden of economic adjustment onto the ordinary people.

In this part, we examine the role the IMF has played in Sri Lanka’s recent debt crisis, building on the arguments developed in Part 1 regarding the lack of theoretical and empirical support for IMF policy prescriptions and the long-term damage they inflict on developing economies. Specifically, we argue that the IMF’s diagnosis, or rather misdiagnosis, of the causes of Sri Lanka’s debt crisis along with its proposed policy solutions exemplifies the flaws in its approach to such crises. Moreover, we contend that its policy recommendations, based on this misdiagnosis, fail to address the underlying structural problems that have led to the crisis and instead exacerbate the vulnerabilities of the economy.

As in many other developing countries, the likely outcome for Sri Lanka if it strictly adheres to IMF policy recommendations is yet another foreign exchange crisis. However, in Sri Lanka’s case, this may well be compounded by a domestic debt crisis.

IMF’s diagnosis of Sri Lanka’s debt crisis and policy recommendations to deal with it

Although the IMF formally acknowledged the damage inflicted on the Sri Lankan economy by the COVID-19 economic lockdown, supply rigidities in its aftermath, and the energy price shocks resulting from the outbreak of the Ukraine war and Western sanctions on Russia, it nevertheless placed the primary blame for the crisis on domestic factors. Specifically, it attributed the crisis mainly to an excessive increase in the narrow money supply (M1), driven by government fiscal excesses financed through money printing by the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL).

Based on this diagnosis of Sri Lanka’s debt crisis, the IMF recommended reducing the budget deficit, ending CBSL money printing to finance it, increasing exchange rate flexibility, and raising both nominal and real interest rates. As part of its insistence on halting money printing, and at the behest of the US government, the IMF also demanded the introduction of a new Central Bank Act (CBA) to replace the existing Monetary Law Act. A key provision of the CBA is the prohibition of the CBSL from directly or indirectly purchasing government debt.

That is to say, it prevents the CBSL from purchasing government debt in primary debt markets as is the practice in many other countries, but also from purchasing, or enabling the purchase of, this debt in secondary debt markets, something which is rarely the practice in other countries. The importance of allowing central banks to have the possibility of purchasing debt in at least secondary markets is that it allows the monetary authorities to have greater control over interest rates.

Problems with the IMF’s diagnosis of Sri Lanka’s debt crisis and corresponding policy recommendations

The first issue with the IMF’s diagnosis of Sri Lanka’s debt crisis that warrants attention is that it is based on the discredited quantity theory of money, albeit in a modified form.

A second, related problem is the illogical nature of this modified quantity theory, which has been—and continues to be—used to explain Sri Lanka’s debt crisis. Specifically, for the IMF, only increases in the money supply arising from printing to fund the budget deficit, whether directly or indirectly, are considered responsible for inflation and external imbalances—not increases in the money supply due to money printing per se.

Third, despite repeatedly claiming that Sri Lanka’s debt crisis—and, more specifically, the surge in inflation that accompanied it—was caused by excessive money printing to fund the Government’s budget deficit, the IMF has provided no empirical evidence to support this contention. In fact, the available evidence on inflation in the 2021–22 period points to the role of supply-side factors, most notably surging energy prices. This is highlighted in the CBSL’s 2023 annual report, which attributes the surge in inflation largely to supply-side factors and even warns that aggressive demand management policies aimed at curbing inflation could exacerbate the supply-side shock (see CBSL, 2024).

Fourth, the IMF’s explanation of Sri Lanka’s debt crisis overlooks the massive and unwarranted accumulation of international sovereign bond (ISB) debt by the Sri Lankan Government between 2015 and 2019 while it was engaged in an Extended Fund Facility (EFF) arrangement with the IMF. By the end of 2019, it had become increasingly evident that Sri Lanka’s foreign debt exposure—particularly its ISB exposure—was so extensive that debt repayment would become problematic. Indeed, it was this accumulation of debt and the perceived inability of the Government to service it that was an important factor in the rapid downgrading of Sri Lanka’s credit worthiness between 2017 and 2019.

Lastly, and perhaps most significantly, the IMF’s diagnosis of Sri Lanka’s debt crisis, like its diagnoses of debt crises in most other developing countries, ignores the underlying structural weaknesses of the economy that led to the crisis. Sri Lanka, like all developing countries, has been assigned a specific role in the global division of labour that renders its trade and current account balances weak and highly vulnerable to major downturns in the global economy. This structural weakness is the root cause of Sri Lanka’s recurrent external payments problems and its repeated reliance on IMF rescue programs.

Consequences of following IMF policy recommendations

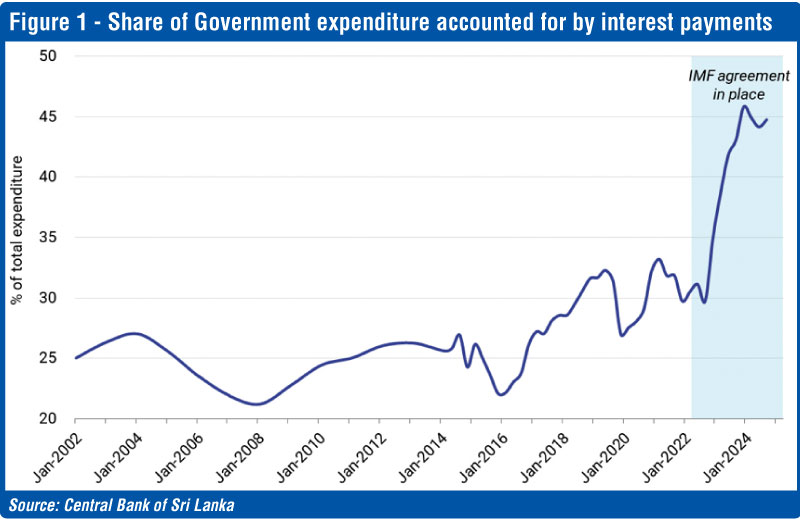

One economic consequence of Sri Lanka’s adoption of the IMF’s policy recommendations is the unsustainably high interest burden it now faces (see Figure 1). The IMF’s emphasis on achieving a primary fiscal surplus (i.e., the fiscal balance excluding interest payments on debt) diverts attention away from the country’s interest burden and towards other aspects of the budget, such as the country’s admittedly narrow tax base. It diverts attention away from the fact that Sri Lanka’s overall debt burden is among the highest of any developing country, and has been rising since the late 1980s despite the budget deficit as a percentage of GDP more than halving. It ignores the fact that the cost of debt servicing places immense pressure on other elements of government expenditure, limiting its ability to invest in essential public services, infrastructure, and social welfare programmes. As a result, fiscal consolidation efforts come at the expense of long-term economic growth and development.

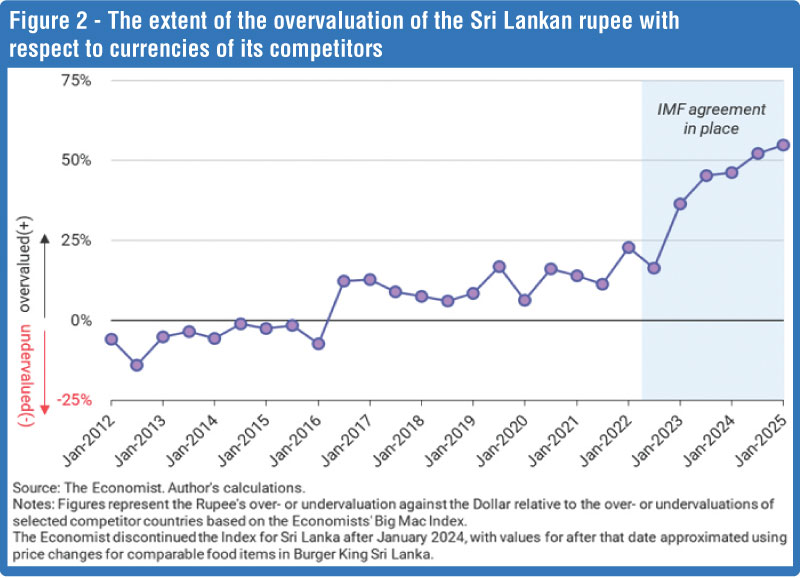

A second major economic consequence of implementing IMF policy recommendations is the continued erosion of Sri Lanka’s international competitiveness. This decline is most evident in the overvaluation of the Sri Lankan rupee (see Figure 2). The increasing overvaluation of the currency is reflective of the weak state of Sri Lanka’s production base, especially its export-oriented and import-substituting industrial sectors (see Nicholas and Nicholas, 2024). This in turn has contributed to the contraction of the country’s industrial production base, further exacerbating trade imbalances and external vulnerabilities. Without meaningful structural reforms to support productive capacity and export diversification, Sri Lanka risks becoming increasingly dependent on external financing, perpetuating a cycle of economic instability and reliance on IMF-led interventions.

It warrants noting that in the aftermath of the debt crisis the IMF repeatedly emphasised that the overvaluation of the Sri Lankan rupee was one of the most important contributory factors in its foreign debt crisis (IMF, 2023). Yet, in its recent reports on the state of the Sri Lankan economy there is barely any mention of this problem, notwithstanding the fact that as Figure 2 shows this problem has only worsened.

Concluding remarks

Parts 1 and 2 of this article have argued that the IMF’s policy recommendations for addressing Sri Lanka’s foreign exchange crisis—as well as similar crises in other developing countries—are, at best, built on tenuous theoretical and empirical foundations. By highlighting these weaknesses, we support the broader argument that the policies the IMF imposes on developing countries seeking its assistance are unlikely to provide sustainable solutions to their foreign exchange challenges. Instead, these measures often lead to a short-term stabilisation of their external reserve positions without addressing the root causes of economic instability, leaving these countries vulnerable to recurring crises.

The case of Sri Lanka’s recent Extended Fund Facility (EFF) agreement with the IMF reinforces this argument. Beyond the usual conditions of deficit reduction and debt-to-GDP targets—common features of IMF agreements with developing economies—the IMF, under pressure from the United States, made parliamentary approval of the Central Bank Act (CBA) a precondition for the EFF’s approval. A key provision of this new legislation is the prohibition on the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) from purchasing government debt, either directly or indirectly. Notably, the IMF provided no substantive evidence to justify the necessity of this policy requirement. To the best of our knowledge, this represents one of the first instances where such a legislative measure has been imposed on a developing country as part of an EFF agreement.

What makes this situation even more striking is that CBSL’s borrowing to finance the budget deficit—both before and during the 2021–22 lockdown period that ultimately led to the foreign debt default—was not exceptionally high by developing country standards (see World Bank, 2024). Despite this, Sri Lanka was subjected to a policy requirement, the CBA, that appears arbitrary and lacking in empirical justification.

Ultimately, this article contends that there is little reason to believe the implementation of Sri Lanka’s current EFF agreement with the IMF will achieve a more sustainable external balance than the 16 previous agreements the country has entered into. Without substantial accompanying policies aimed at restoring the ability of the CBSL to purchase Government debt, promoting export-oriented industrialisation and addressing structural weaknesses in the economy, there is every reason to doubt the program’s long-term effectiveness. The real question is not whether Sri Lanka will experience another foreign exchange crisis, but when it will occur and what its economic and political consequences will be.

References:

CBSL (2024) The Central Bank of Sri Lanka Annual Report 2023. Colombo: Central Bank of Sri Lanka.

Nicholas, H and Nicholas, B. (2024). Daily FT, 14th March, https://www.ft.lk/columns/The-silent-killer-economic-consequences-of-an-overvalued-exchange-rate/4-759445.

Nicholas, H and Nicholas, B. (2025). Why following IMF policy recommendations will lead to yet another debt crisis: Part 1. Daily FT, 20th March, https://www.ft.lk/opinion/Why-following-IMF-policy-recommendations-will-lead-to-yet-another-debt-crisis-Part-1/14-774479.

Part 1 of this article can be seen at https://www.ft.lk/opinion/Why-following-IMF-policy-recommendations-will-lead-to-yet-another-debt-crisis-Part-1/14-774479