Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Saturday, 19 January 2019 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

“Incessant monsoonal rains during the last week of May 2017 triggered floods and landslides across Sri Lanka, affecting over half a million people and according to national authorities, killing over 200 people. “I was five months pregnant when the floods came. I had to go to my friend’s house up the mountain for safety with my 2.5-year-old daughter,” said Priyanka, 32. Standing outside her house later, a stone’s throw from the river banks, you can imagine how terrifying it would have been to watch the flood waters rise to your house. Priyanka and her family were unharmed, but her husband’s business was destroyed, affecting their livelihoods”

– International Planned Parenthood Federation

Owing to climate change, natural disasters have become an almost commonplace occurrence in the world. Developing countries, especially island nations like Sri Lanka, are particularly prone to such disasters, due to two reasons; their geographical location, which is vulnerable to the rising sea levels, and their limited capacity to adapt, due to the lack of access to financial resources and technologies.

Owing to climate change, natural disasters have become an almost commonplace occurrence in the world. Developing countries, especially island nations like Sri Lanka, are particularly prone to such disasters, due to two reasons; their geographical location, which is vulnerable to the rising sea levels, and their limited capacity to adapt, due to the lack of access to financial resources and technologies.

Unfortunately, natural disasters have a gender aspect, where women are often affected more severely than men. A woman’s pre-disaster familial responsibilities are magnified and expanded by a disaster, often with significantly less support and resources. This does not mean that men are not affected at all; but, given that women are often in a disadvantaged position in many contexts, the promotion of gender equality implies that attention need to be paid to female empowerment in disaster management (DM).

Gender and disaster management

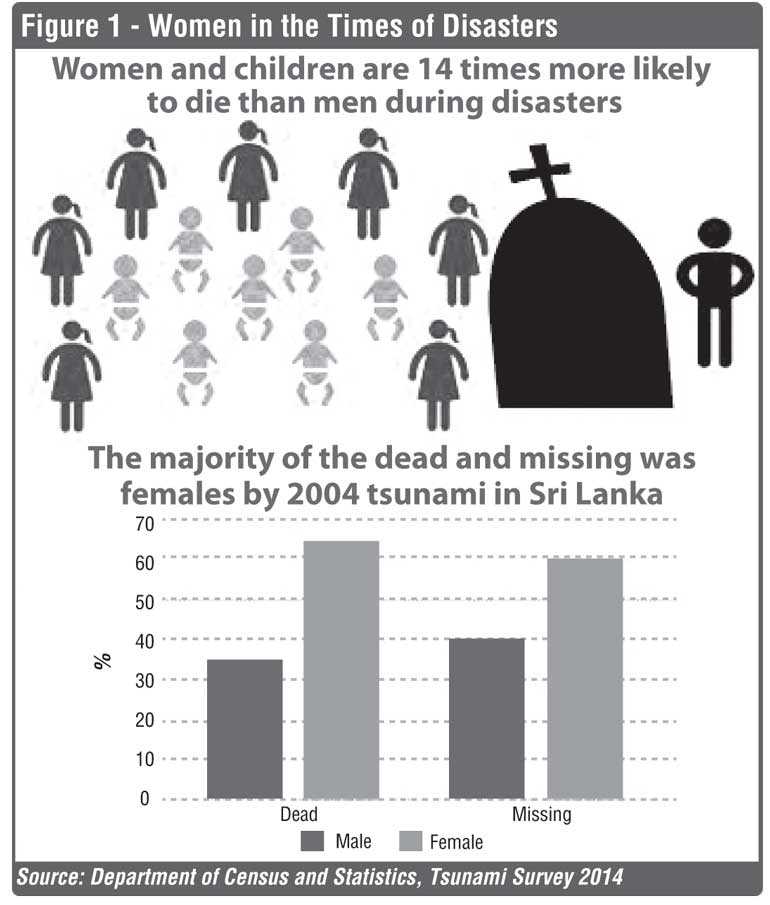

Experiences from different parts of the world show that women are more vulnerable to the impacts of natural disasters. In fact, women and children are 14 times more likely to die than men during disasters. For instance, when the devastating tsunami hit Sri Lanka in 2004, the majority of the dead and missing was females (Figure 1). It was easier for men to survive during the tsunami because swimming and climbing trees are skills mainly taught to boys.

Gender makes differences in all aspects of a disaster; vulnerability, resilience, and recovery. Additionally, the four basic components of DM, mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery, are directly linked with gender. Hence, the needs and vulnerabilities of men and women and their capacities and priorities should be considered separately in DM.

Disaster management and gender mainstreaming in Sri Lanka

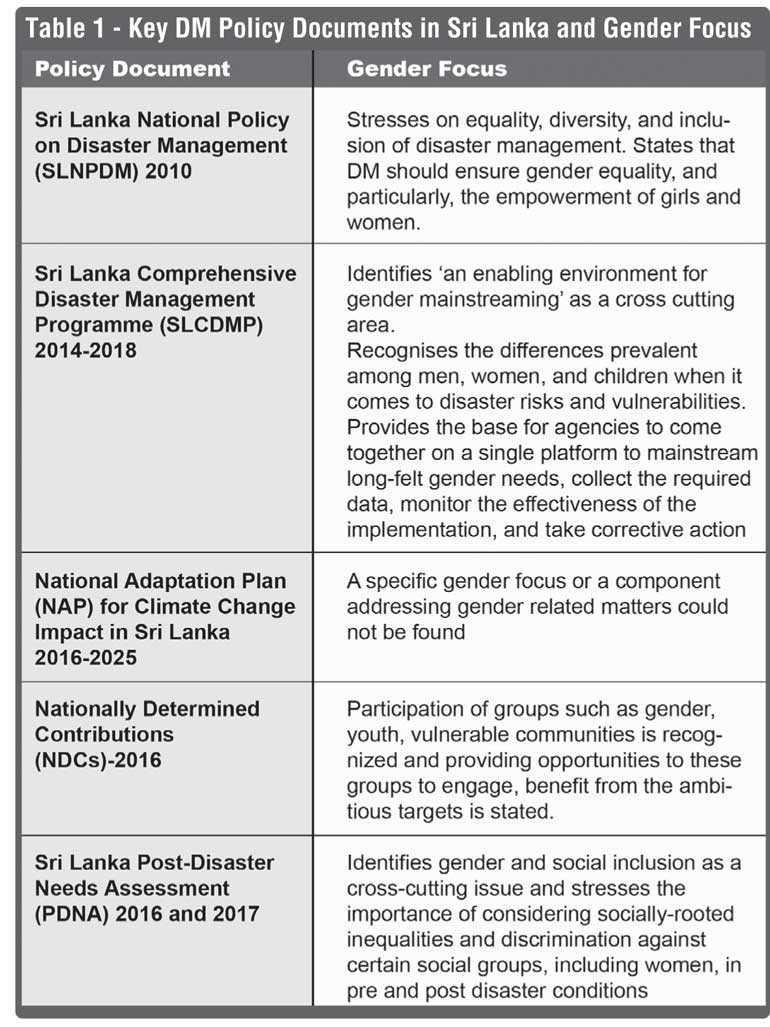

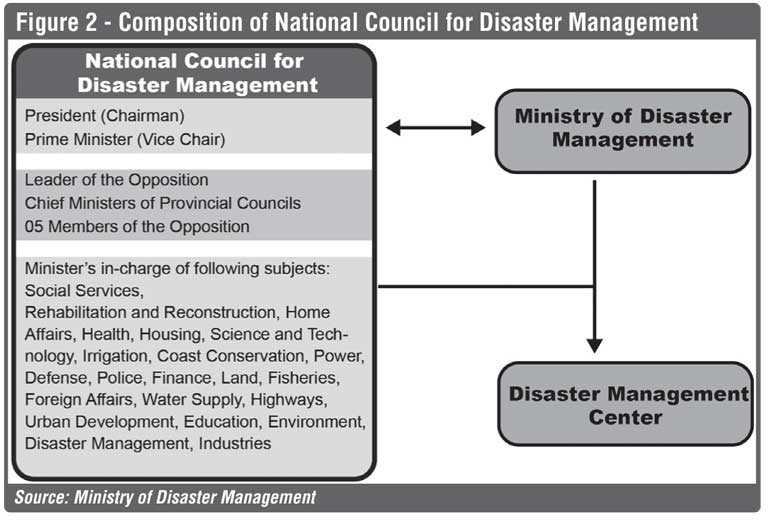

According to the Sri Lanka Disaster Management Act No. 13 of 2005, the National Council for Disaster Management (NCDM) is the supreme body for disaster management in Sri Lanka. In the recent years, there have been some promising initiatives in mainstreaming gender issues into the DM policies of Sri Lanka. However, the level of gender consideration varies among those documents (Table 1).

Policies in practice: Issues and way forward

Despite some progress in the recent past, there are gaps in addressing gender issues especially at the implementation level in Sri Lanka.

A major issue in this regard is the low participation of women in the pre and post disaster decision-making process at all the levels. This leads to gender blindness in DM projects. For an example, NCDM, the supreme body for DM in Sri Lanka, consists of the President, the Prime Minister, Chief Ministers, five members from the opposition, and several Ministers. But there is no representation from the Ministry if Women’s Affairs (Figure 2). Further, there is an overall poor engagement of women when it comes to the delivery of early warnings and the preparedness for response, both at the community and local official levels.

Therefore, it is important to enhance women’s participation in the decision-making process at all levels. It has been observed that women’s representation at the national level as well as at the community level is weak and there is a limited space for their voice. A compulsory number or a quota for female representation can be introduced for committees at all levels as an  initial step in addressing this issue and measures have to be taken to ensure female representation. A participatory approach is proposed to ensure equal and gender-sensitive participation of women and men, leading to better DM policy and programme designs.

initial step in addressing this issue and measures have to be taken to ensure female representation. A participatory approach is proposed to ensure equal and gender-sensitive participation of women and men, leading to better DM policy and programme designs.

The lack of sex-disaggregated data in Sri Lanka is another challenge. Generating disaster related sex-disaggregated data is important to properly understand and analyse the gendered aspects of disasters. The unavailability of such data hampers informed planning, decision-making, and the provision of appropriate support in pre and post disaster situations.

Establishing a strong and reliable national level mechanism to generate sex-disaggregated data should be considered a top priority, as such data would facilitate more effective and sustainable humanitarian responses and indicate the direction for future policy needs. At the same time, it is also important that policy makers, implementers, researchers and other stakeholders use sex-disaggregated data as much as possible in order to understand the gendered aspect of disasters.

Finally, there should be gender sensitive spacing arrangements in temporary shelters. Privacy for women and girls in living spaces, segregated sanitation facilities, including menstrual hygiene management, are major concerns in temporary welfare centres. Similarly, expecting and lactating mothers face hardships in meeting their specific requirements in these centres. In this regard, it is important to take measures to ensure that women and girls meet their needs in temporary shelters. When setting up temporary shelters, attention should be paid to designing them in a manner which facilitate specific needs of women.

[This blog is based on a chapter written for the ‘Sri Lanka: State of the Economy 2018’ report, IPS’ annual flagship publication. Sunimalee Madurawala is a Research Economist at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS). To talk to the author, email [email protected]. To view this article online and to share your comments, visit the IPS Blog ‘Talking Economics’ – http://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/.]