Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday, 16 October 2015 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The five largest SOEs – CEB, CPC, Sri Lanka Ports Authority, Bank of Ceylon and People’s Bank – exceeded the turnover of all 245 companies listed in the Colombo Stock Exchange

The history of State-Owned-Enterprises (SOEs) goes back to British colonial rule. Even after the Independence, ownership and management of commercial enterprises by the state were, justified by the parties identified with socialist ideology.

State involvement in businesses increased due to regimes which gained power on a populist agenda. This trend was reinforced by a wave of thinking which advocated insulating developing countries from the vagaries of an international economic system which was dominated by advanced countries and their MNCs.

These statist economic policies steadily grew and gathered further momentum in the 1970s when government policy, in the name of socialist or progressive reforms, sought to gain control of the “commanding heights of the economy”. However, Sri Lanka’s production/distribution of goods and provision of certain services, including mass transportation, was rolled back after the election of the J.R. Jayawardena Government in 1977.

Successive governments, up until 2005, privatised a considerable number of SOEs. Since then, however, the process has come to a halt. As a result, SOEs still account for a significant share of the economy and their losses and inefficiencies substantially contribute to the retardation of growth and development of the country.

Role and burden of SOEs on the Sri Lankan economy

There are 81 SOEs and the Government is also a partial owner of several entities established under the Companies Act of no.07 of 2007. Let us look at the plight of these SOEs in 2010. Data provide insights to the extent of the losses and inefficiencies incurred by these institutions and the burden it has put on the country’s economy Total turnover of SOEs amounted to Rs. 954 billion.

The five largest SOEs [CEB, CPC, Sri Lanka Ports Authority (SLPA), Bank of Ceylon (BoC), People’s Bank (PB)], exceeded the turnover of all 245 companies listed in the Colombo Stock Exchange. In addition, SOEs accounted for 17.2% of GDP and employed 160,000 people (2010).

The size of the SOE sector, as well as the breadth of its activities across the economy, makes it a crucial determinant of the overall productivity of the economy and therefore, the level of wages that can be sustained without fuelling inflation. The difficulties experienced in accommodating international prices of key imports, like fuel, without unduly burdening the people through its impact on the cost of living, may be attributed to the low productivity/low wage syndrome in the economy. The underperformance of SOEs is a major part of this narrative.

All SOEs are expected to contribute 30% of their profits or 15% of their equity, whichever is higher, to the Consolidated Fund. Such levies and dividends from SOEs amounted to Rs. 31 billion in 2010. However, the CPC, CEB, SLPA and National Water Supply and Drainage Board (NWS&DB) alone made combined losses of Rs. 48 billion in that year. Furthermore, the CPC and CEB on their own made a loss of Rs. 130 billion in 2011 (this amount is sufficient to build 130 high class schools or 65 300-bed hospitals), while SriLankan Airlines/Mihin Air recorded losses of Rs. 13 b. These figures do not include the accumulated losses of SOEs or the government guarantees issued to them.

As Sri Lanka becomes more exposed to capital markets and rating agencies, the financial health of the SOE sector and its direct and indirect impact on the Government budget will become more important as a determinant of the country’s creditworthiness.

It should be pointed out that there has being some improvement in the performance of SOEs since 2010. However, they continue to be a burden on the budget and undermine the balance sheets of state banks with their accumulated losses. As a result, SOEs continue to be a major drag on the economic prospects of the country through both their financial losses and the low returns they generate on the resources (capital and labour) they absorb.

Political leaders, professionals, and officials complain: Why then no action?

Time and time again senior politicians have deplored the status of SOEs and complained about the burden these institutions place on the people of Sri Lanka but have failed to implement concrete actions to privatise them or at least to introduce Public/Private Partnerships (PPPs).

Some time back a respected senior minister spoke of a number of ‘monsters’ that undermine Sri Lanka’s development prospects. These monsters are the SOEs which incur large losses that eventually have to be borne by the people of this country through higher direct or indirect taxes.

The losses of SOEs, such as the Sri Lanka Transport Board (SLTB), CPC, CEB and SriLankan Airlines/Mihin Air are due to many reasons including mismanagement, corruption, political interference, non-cost-reflective pricing policies and also the utter disregard for pubic assets and money. In this respect, the past Performance Reports of the Department of Public Enterprises, Ministry of Finance, identifies a number of factors that contribute to the large losses incurred by the SOE sector.

“Loss making SOEs continue to incur losses due to lack of good governance, low productive use of employees, weak financial management, lack of internal controls and structural deficiencies. It is noted that Boards of Management of some key SOEs, which have often made decisions that were neither socially nor economically viable, violating government policies nor regulations, contributed significantly to the losses incurred by SOEs.”

The problems have being diagnosed. However, remedial action has been stymied by political expedience driven by ill-advised populism and/or misplaced ideology. It is also reported that leaders of this country including those who become ministers consider the public enterprises as their private property to be utilised by Kith and kin.

Why doing business by government cannot deliver the most efficient and profitable outcomes

Unfortunately, government reports and even certain independent analysts ignore what is fundamentally wrong with having the state entering into business in general and especially in the Sri Lankan context. They only highlight the impact on the annual government budget and the general inefficiencies arising out of poor management practices and political interference in public enterprises rather than focusing on the underlying factors which compromised the performance of SOEs.

Instead of re-inventing the wheel let us focus on a recently published commentary by John Steel Gordon in The Wall Street Journal. There he provides a number of reasons why governments should not and can’t run enterprises.

1. Governments are run by politicians, not businessmen

They are, after all, first and foremost in the re-election business. Because of the need to be re-elected, politicians are always likely to have a short-term bias. What looks good right now is more important to politicians than long-term consequences even when those consequences can be easily foreseen. And politicians tend to favour parochial interests over sound economic sense.

2. Politicians need headlines

This means they have a deep need to do something, even when doing nothing (in Sri Lankan context saying nothing) would be the better option. Markets will always deal efficiently with gluts and shortages, but letting the market work doesn't produce favourable headlines.

3. Governments use other people's money.

Corporations (private enterprises) play with their own money. This disciplines their commercial behaviour. SOEs have access to public funds/guarantees which encourages a lack of attention to the need for competitiveness/profitability. At the same time, the people are not sufficiently aware to exercise their rights to ensure accountability regarding the way in which their money is being wasted. That is why governments in Sri Lanka have always been over generous in providing employment in the state sector and excessive salary increases with no corresponding relations to performance.

4. Government enterprises are almost always monopolies or at least do not allow competitors to operate on a level playing field

Therefore, if efficiency and performance is to be improved in providing goods or services, SOEs are the worst possible option for a country aiming to be competitive internationally.

Who is against privatisation?

The political leaders, while publicly stating the need for corrective action in public enterprise management, simply back out from urgently needed reforms bowing down to pressures from trade unions, and other rent-seeking beneficiaries and corrupt ‘stakeholders. Most notably, the Ministers in charge of or who consider these SOEs as being under their purview are determined to prevent any attempt at broad basing the ownership or strengthening management.

This is simply due to their desire and intent for continuing with miss management and corrupt practices so that SOEs can continue to be sources of political patronage rather than providers of goods and services at competitive costs and of high quality. The Ministers in general have considered the public enterprises under their control as institutions for providing lucrative employment for friends and family.

The other organised group, which resists any form of restructuring of public enterprises, are the workers, including professionals and white-collar workers. Of course reform or change always creates uncertainty and a sense of insecurity in the minds of SOEs that are generally over-staffed. In dealing with trade unions, therefore, the government needs to understand this reality and introduce a social safety-net to take care of any possible negative outcome of privatisation and post-privatisation impacts.

New Government, change of policy and hopefully, implementation as priority

Given the above scenario, any regime or sensible leadership has very little or no choice other than gradually withdrawing government from state ownership/management of commercial enterprises. In realising this objective the present government has emphasised the need for a ‘Temasek Model’ to manage the SOEs. The Temasek model has been successfully implemented by the Singaporean government.

Temasek is a holding company which owns assets and shares of previously government owned commercial enterprises. When the Singaporean government became independent it inherited a number of SOEs which were in a sense gradually floated in the share market of Singapore through the Temasek model.

The present administration, which intends to follow the same format, is likely to transfer currently government-held shares of SOEs to an entity modelled in line with Temasek. The current creation of one ministry to be in charge of a number of commercial public enterprises seems a sound approach towards creating such a holding company.

However, this ministry does not have under its purview several other key SOEs, including CEB, CPC, NWS&DB, Ceylon Railways and a few others. For these, the first step should be to move to cost-reflective-pricing. Social protection objectives should be met by targeted income transfers (and cross-subsidisation) rather than unaffordable universal subsidies.

Options should also to be considered to greater competition to provide people with cheaper and better quality services. The successful privatisation of the telecommunication sector is an excellent example of what is possible in this regard. Sri Lanka has some of the lowest tariffs in the region.

Broad-basing SOEs: Increasing efficiency, reducing debt and generating revenue

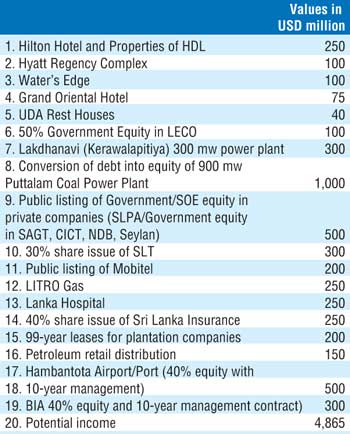

The Pathfinder Foundation came across a recent estimate of potential gains in terms of revenue simply through listing of shares of a section of SOEs. The estimated values are based on numerous reports, loans obtained for constructions, etc.

Listing of SOEs will increase the market capitalisation of CSE, promote foreign investments and widen the Government tax base (see table).

Based on these transactions undertaken through CSE and possibly through double listing in Hong Kong and London, the Government could also raise a 20 year international bond of approximately $ 2,000 million, which will ease overall debt management.

Much more opportunities for increasing revenue, enhancing efficiency

In addition to CSE-based broadening of ownership, the Government could encourage foreign and local investors to enter into much longer term management contracts with plantation companies. Funding of infrastructure development under Western Region Megapolis, the existing and new facilities of arts, culture, entertainment, film locations, etc., could be developed on BOO and BOT basis.

Leasing of railway facilities for tourism operators, contract out management of Export Processing Zones as well as management of sewerage systems and garbage disposal in metropolitan areas will not only generate revenue for the Government but create space for increased spending on health, education, and provisions for disadvantaged people.

Time for action

Sri Lanka’s economic prospects are severely constrained by the underperformance of SOEs. There are well-known reasons why governments mismanage commercial enterprises. The country’s budget deficit (including the quasi fiscal deficit setting on the balance sheets of the State banks) and debt dynamics make SOE reforms an urgent priority. This will stem the losses which ultimately cast a burden on the people through increased taxes and/or inflation. It will also mobilise much-needed revenue for the Government. Most importantly, as the telecommunication sector has shown, it will bring better services for the people. The options available for the policy makers include listing on the share market, strategic investors, outright sale or private management.

(This is the 69th Economic Flash of Pathfinder Foundation. Readers’ comments are welcome at www.pathfinderfoundation.org.)