Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Tuesday, 2 June 2015 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Reuters: A slide in the Philippines’ economic growth to its weakest in three years wraps up a slew of dismal data from Southeast Asia and adds pressure on governments to unleash some of their fiscal spending firepower given the limitation of monetary policy now.

After years of low interest rates and cheap money, consumers and companies across much of the region are burdened by weighty debts, making monetary stimulus less effective. An expected uptick in inflation also suggests limited room for further rate cuts.

“Monetary policy has lost its punch...but we’re not really seeing the fiscal authorities step up,” said economist Fred Neumann at HSBC bank.

Southeast Asian economies are losing momentum and recent data offers little hope of a rebound in the second quarter, especially as demand from regional powerhouse China sputters.

Yet governments seem unable to spend, even after falling oil prices delivered big budget windfalls, as political stalemates and corruption probes create bottlenecks for investment.

Philippine January-March annual growth slipped to its slowest in more than three years due to weak exports and public spending, data showed on Thursday. Meanwhile, annual growth in Indonesia, the region’s largest economy, dropped to a six-year low. Growth moderated in Malaysia, too.

When world oil prices plunged in mid-2014, making the region’s near-universal energy subsidies less costly, many economists predicted a big boost from government spending which hasn’t materialised.

“Now, nearly a year later, it has become obvious that fiscal policy stimulus has simply failed to gain traction in a number of key economies,” ANZ bank said in a research report.

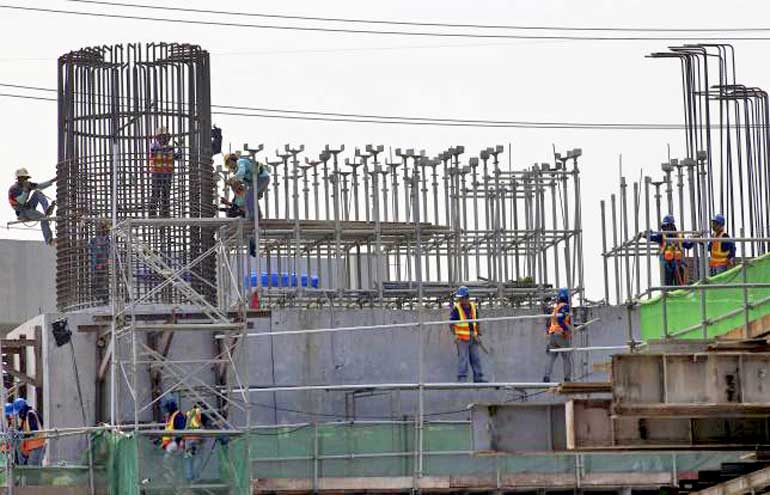

In Indonesia, President Joko Widodo took advantage of cheap oil to scrap petrol subsidies and channel the savings into infrastructure improvements. But by mid-May, less than 4 percent of the government’s $22 billion capital budget for this year had been spent, as many projects remain tied up in red tape.

Thailand’s military government wants to spend $98 billion on infrastructure by 2022, but many economists doubt it will manage. Almost eight months into the fiscal year that began in October, two-thirds of the $10 billion budget for capital projects is unspent as the junta seeks to combat corruption.

“We think government infrastructure investment will continue to face high risk of delays,” Credit Suisse’s Santitarn Sathirathai said in a report, as he cut his Thai growth forecast for this year to 3.1% from 3.7%.

President Benigno Aquino’s government in the Philippines has also spent less than planned, and slow budget disbursal dragged down first-quarter growth.

“Public spending is simply not recovering from the lingering effects of a corruption scandal,” said ANZ.

Monetary stimulus

Governments have been leaning on central banks to deploy stimulus, but with inflation looking set to pick up, it is becoming harder for policymakers to add to recent rate cuts.

Central banks are worried about high household debt and capital outflows when US interest rates rise. The rupiah is Southeast Asia’s worst-performing currency this year, down by about 6% against the dollar.

After data showed government spending stalled in the first quarter, contributing to weak growth, Bank Indonesia Governor Agus Martowardojo said Widodo’s budget would not boost growth unless the money was spent.

“It came with a huge responsibility to execute the budget in a timely manner,” he said.

Only in Malaysia, which as a net oil exporter has been hit hard by sliding crude prices, does a big budget deficit and relatively high public debt make pump-priming risky.

Cheap oil allowed Prime Minister Najib Razak to get rid of fuel subsidies, but his government is reeling from a collapse in petrodollar receipts, which account for 30% of its revenue.

HSBC’s Neumann said fiscal conservatism was preventing other governments from using tax cuts or similar handouts that might boost growth sooner. “They could afford it, but they’re still not doing it.”