Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday, 1 August 2017 00:05 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

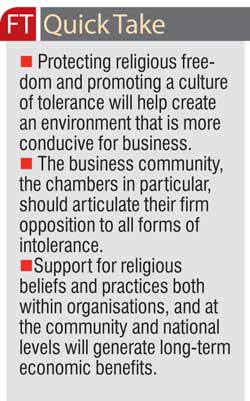

Promoting peace and co-existence in contexts where religious groups show great gusto in emphasising their distinctiveness, as opposed to their commonalities, can be tremendously challenging. Yet it is a fallacy to think that religious diversity is at odds with social cohesion

–Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

By Ayesha Zuhair

A few years ago, during the course of a conversation with an overseas-based Sri Lankan academic who was then in Colombo on a short vacation, I was struck by a remark he made on the growing religiosity of Sri Lankan society. He discerned that Sri Lankans, broadly speaking, were becoming increasingly assertive of their religious identities, and reckoned that this development did not bode well for our future. The growing influence of religion, he opined, was going to be one of the next major challenges.

My immediate reaction was, “If people are becoming more conscious of their religious identities, is this something we should be afraid of?” His response was that it could become a matter of concern if the assertion of a particular religious identity has an impact on others. The basic underlying assumption here was fairly clear; the more ‘religious’ a society was, the greater the propensity for dissonance and even violence.

The link between religion and conflict has been the subject of much debate over a long period of time, attracting much attention post 9/11. It is not a debate that will end any time soon. For many secular thinkers, religious beliefs and their various manifestations represents an impediment to the creation of harmonious, cohesive societies – because of disagreements over what constitutes ‘the truth’. They seem convinced that a policy of ignoring or marginalising religious believers/groups is a necessary requisite for unity.

Granted, promoting peace and co-existence in contexts where religious groups show great gusto in emphasising their distinctiveness, as opposed to their commonalities, can be tremendously challenging. Yet it is a fallacy to think that religious diversity is at odds with social cohesion. Religion is not a gremlin to be contained; it can actually be a powerful counterweight to narcissist, supremacist thinking and a force that unites, not necessarily divides. It should be seen as such and its potential recognised.

As Karen Armstrong, one of the world’s leading thinkers on comparative religion, has correctly noted, every single one of the world’s major religions accords pride of place to the concept of compassion – the ability to feel with the other. The Golden Rule in all religions is ‘Do unto others as you would have them do unto you’. This, if applied with true religiosity, helps adherents to view matters in a broader – not narrower – perspective.

The real problem in my view, is not increased spirituality, which by itself would most certainly be a welcome advancement. Rather, it is the shrinking space for religious freedom, expression and most importantly, tolerance. Sri Lanka’s recent history, unfortunately, is littered with incidents that point not to the country’s supposed religiosity but to growing intolerance of differences. This is borne out in the recent spate of attacks on minority-owned business and places of worship in the country, and also in the manner in which advocates for minority rights have been targeted.

Religious sensitivity vs. intolerance

On 19 July, an Indian tourist was arrested and detained by the Sri Lankan Police for wearing a dress with an image depicting the Buddha. In April 2014, a British tourist was deported from Sri Lanka because of a tattoo of the Buddha on her arm. Previously in March 2013, another British tourist was also deported for displaying a Buddha tattoo on his arm. These incidents, to me, do not constitute religious intolerance. Religious sensitivity is important even as we open our arms to foreign visitors.

Threats, intimidation and hate speech as well as direct attacks on religiously and culturally distinct communities, however, are manifestations of intolerance that have no place in a civilised, democratic society. It is necessary to bridge the gap that exists in terms of legal action taken against perpetrators of such acts, but this alone will not suffice to promote sensitivity and confront intolerance.

As evidenced in Aluthgama, where tolerance has a weak societal foundation, it is easy for political entrepreneurs to mobilise mobs to wreak havoc on innocents. This is an area where intervention is required. Businesses can step in as agents of peacebuilding and devise long-term strategies to promote mutual respect and cross-cultural understanding at the community level as part of their CSR initiatives. They could identify places that are particularly susceptible to outbreaks of religious hostilities, and draw up / support programmes joining hands with religious leaders to encourage inter-faith dialogue, social harmony and justice with a view to repairing deeply damaged social relationships.

Religious freedom has economic benefits

Religious freedom is one of the factors significantly linked to economic growth. According to a 2014 study by researchers in Georgetown University and Brigham Young University, freedom of belief is one of vital factors that contribute to economic success. The study looked at the GDP (Gross Domestic Product) of 143 countries while controlling for other theoretical, economic, political, social, and demographic factors. It also found that innovative strength was more than twice as likely in countries among low religious restrictions and hostilities.

It noted: “…religious hostilities and restrictions create climates that can drive away local and foreign investment, undermine sustainable development, and disrupt huge sectors of economies. Such has occurred in the ongoing cycle of religious regulation and hostilities in Egypt, which has adversely affected the tourism industry, among other sectors. Perhaps most significant for future economic growth… young entrepreneurs are pushed to take their talents elsewhere due to the instability associated with high and rising religious restrictions and hostilities.”

Sri Lanka is at a juncture where it needs to reverse the rising tide of intolerance, in all its forms. Beyond their immediate impact in tangible terms, religious tensions will decrease Sri Lanka’s attractiveness as a business destination. The business community, the chambers in particular, can play a vital role in addressing this issue. Ensuring freedom of religion and promoting a culture where differences are tolerated is crucial to create a climate conducive for business. Foreign investment is especially needed to create opportunities for growth in the country’s poorest districts.

The country’s national debt is a huge concern as Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe has acknowledged. At the foundation-stone laying ceremony for the Viyathpura Green Professional City in Pannipitiya on 17 July, the Prime Minister stated that the total debt which the country has to repay within the next three years is Rs. 4.2 trillion. He stressed the need to build up a competitive market economy if the country was to be debt free.

Deputy Minister of Policy Planning and Economic Development Dr. Harsha De Silva at a recent panel discussion on the benefits of the GSP Plus trade concessions called for a culture of innovation and entrepreneurship, and the need to move away from a culture of entitlement to overcome the challenges facing the country. Businesses can help create an environment for this. One of the ways they can do this is by articulating their opposition to intolerance and being proactive in discouraging religious confrontations.

Space to flourish

Religious influence on society is not an entirely new concern as noted previously nor is it one that is unique to Sri Lanka. But the role of religion in society is not one that is always fully understood by secularists as a result of which they can at time be anti-religious in outlook. All religions should have the space to flourish; across the board they all incorporate principles of peace, justice and equality and these are the values that have to be tapped into in order to build a culture of tolerance.

Those who feel strongly connected to their religious and cultural beliefs as well as their social systems often feel threatened when outsiders try to ‘reform’ or ‘interfere with’ their way of life. As Karen Armstrong has argued quite convincingly, secularisation when applied forcibly has provoked a fundamentalist reaction and history shows that movements which come under attack invariably grow more extreme as the experience of the Middle East exemplifies.

If Sri Lanka is to gain a reputation as an attractive destination for international business, religious intolerance needs to be a part of our history, not future. Furthermore, religion need not be viewed suspiciously or contemptuously. In a world where religion has been hijacked, an unhealthy fear of religion is exactly what zealots want. We must not play into their hands.