Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Monday, 4 April 2016 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Niyanthini Kadirgamar

By Niyanthini Kadirgamar

In the post-war North and East housing is a dire need. The provision of permanent housing, as well as livelihood creation, is pivotal for the resettlement of communities. As such, a Cabinet decision to build 65,000 houses for war-affected communities seemed to be a move in the right direction for a Government that came into power on promises of reconciliation and economic prosperity.

However, with a foreign contractor about to be handed the task of handling the housing project, many have now labelled the initiative a disaster deal and hope is fast fading. The deal will offer Arcelor Mittal, a company headquartered in Luxemburg, a contract to build 65,000 prefabricated steel houses, which are to be imported and assembled within a short period of time.

That the drop in steel prices in the world market and losses for the world’s leading steel producer led to the decision to seek out a post-war destination to export ready-made steel is understandable. However, as to why the Sri Lankan Government agreed to make Sri Lanka a dumping ground for a multinational is more baffling. Does this point to a continuing failure to initiate reconstruction and curb increasing economic costs such as that seen during the rule of the previous Government?

Foreign loan and economic impact

It is in the wake of an announcement that the excessive foreign borrowing of the previous regime has contributed to the present economic crisis that the deal is being negotiated.

Each steel house that Arcelor will build costs Rs. 2.1 million. Thus, the Government will incur a foreign debt of about $ 1 billion for the 65,000 houses, to be paid back over a 10-year period.

A financing arrangement through HSBC offers two options – a six month EU currency-based facility at EURIBOR +1.34% and a six-month US dollar-based facility at LIBOR +1.74%.

These concessionary rates apply to 85% of the loan. The remaining 15% will be based on commercial rates of LIBOR +5.61%. For example, based on the current rates for LIBOR, the applicable interest rate for the loan is 3.23%.

Perhaps the Government is attracted by the opportunity to take this loan and show macroeconomic growth. Certainly, such large-scale construction activities will account as economic activities of the country and contribute to its GDP figures.

However, taking another massive loan will only add to the crisis by continuing to increase our foreign debt. It will deplete our foreign reserves and add to our future balance of payment problems. Although the financing comes with a one-year grace period, the Government will eventually have to pay back the dollar loan. A few years down the line it may contribute to another similar crisis like the one we are presently experiencing.

Alternatively, obtaining financing for the housing project through local financing will have less impact on the country’s external finances. The required financing can be raised through a combination of Government fund allocation, local bank borrowings and an arrangement with a donor agency like the ADB. This is how many of our highways and roads have been built. Housing should be a more important priority than highways.

Costs of building

Costs of building

Previous housing schemes, like the one constructed with an Indian housing grant, were built for a much lower cost of Rs. 550,000. Local analysts point out that this amount was insufficient to build a good quality house and many recipients were compelled to obtain loans in order to complete it.

According to current estimates, a good quality traditional concrete house of 550 square feet can be built for anywhere from Rs. 800,000-Rs. 1 million. Thus, the cost of building 65,000 houses can be limited to $ 500 million.

Furthermore, based on these cost measures, if the Government is to allocate the current budget of $ 1 billion, the entire housing need for the North and East, estimated as 137,000 houses, can be fulfilled.

The Rs. 2.1 million proposed by Arcelor Mittal for a steel house is too expensive. While the economic costs of pursuing this deal is great, the social costs of going ahead with prefabricated steel houses is greater.

Steel houses are unsuitable for our local climate and lifestyle. Furthermore, concerns about the durability for long-term dwelling and toxic nature of the material used have been voiced. If the communities were consulted, it is certain that no displaced person would choose steel over brick and mortar in the construction of their house.

Underlying the belief that such projects can be forced through without proper consultation with local communities, is the blatant disregard shown by the state in fulfilling the needs of marginalised sections of society. However, permanent reminders of such disregard, in the form of one’s own dwellings, may have greater political costs for the Government.

Economic stimulus and benefits for the people

There is a major opportunity cost for a reconstruction project of such prefabricated houses; it is not just about GDP growth. A massive loan on the scale of $ 1 billion can produce a multiplier effect if utilised as investment in the local economy.

Opting for imported prefabricated houses, however, will only benefit the foreign contractor with a sizeable profit and leave the country dry. Had the Government chosen to fund a locally-driven model for building the houses even at a cost of $ 500 million, it could have been a significant economic stimulus. For that the Government must ensure local labour and local materials are utilised for building.

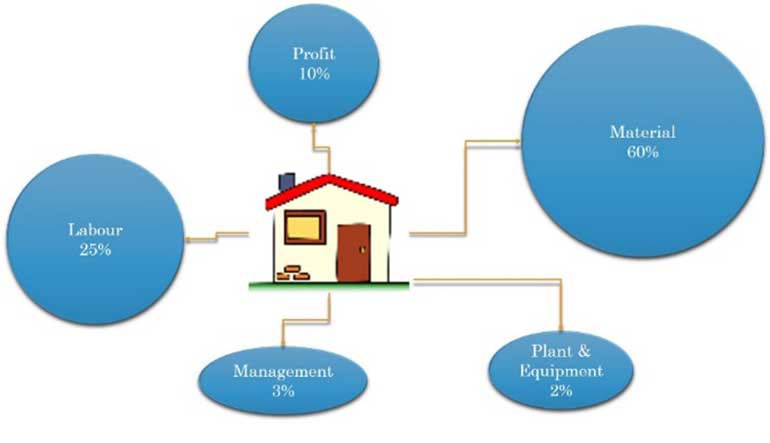

25% of the share of the cost of building a house is spent on skilled and unskilled labour. The remaining is spent on material (60%), management (3%), plant and equipment (2%) and profits (10%).

The share for labour of a house costing Rs. 1 million is Rs. 250,000. It is equivalent to a construction worker’s yearly income in the North. Thus, 65,000 houses can provide income for 13,000 workers over a period of five years. It could mean steady income for 13,000 households or 52,000 people.

There are around 17,500 skilled labourers (masons, carpenters, welders, plumbers, electricians, etc.) available in the Jaffna District alone (District Secretariat, 2014 statistics). The available labour pool for construction works in the North, however, is much larger when including unskilled day labourers in Jaffna and skilled and unskilled labourers in all five districts.

Income can be generated for local industries by utilising local material for building (cement, sand, concrete blocks, bricks, steel, timber, plumbing, sanitary items, electrical items, tiles, ceiling, chemicals, paint). Thus, more indirect employment through linked local industries and the provision of support services can be created.

Over the past several years, resettled communities that have returned to war-ravaged villages faced with complete erasure have acquired valuable knowledge and skills, including expertise on construction and homebuilding. Community-led construction of houses can not only ensure an equitable process but can also help strengthen the resilience of local organisations such as cooperatives, rural development societies and women’s rural development societies.

Why do they fail?

Reconstruction of the North and East has been slow. Investments for new industries that can generate steady employment or revive traditional livelihoods have failed to come through.

The Government will promise to raise funds for long-term development at a donor conference later this year. However, given the declining income from traditional livelihoods and the slow progress in creating new jobs for people, there is a desperate need in the North and East for immediate employment.

It is through infrastructure and housing projects that large sections of people in the North and East managed to earn a living in the post-war years. A construction project like the one which will create 65,000 houses could meet that immediate need for employment if those from the North and East are included in the construction work.

It is baffling as to why the Government will spend $ 1 billion and let go of an opportunity to invest in stimulating the local economy. Why does the Government continuously ignore the genuine economic upliftment of the people for jobless economic growth on debt?

As with many other development initiatives, we are repeatedly faced with the same dilemma of disconnect between the Government’s economic policy decisions and the socioeconomic needs of the people.

While large foreign loans are obtained for the sake of development, what is passed down to the people often fails to improve their lives in meaningful ways. Granting the project to erect 65,000 houses to Arcelor Mittal to dump prefabricated steel houses might become one of the disastrous examples of development failing the Sri Lankan people.

(Niyanthini Kadirgamar is a researcher based in Jaffna and a member of the Collective for Economic Democratisation)