Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Wednesday, 5 October 2016 00:01 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Frances Bulathsinghala

The life of 25-year-old Rathika Pathmanathan is a testimony of a post-war nation at the crossroads. She has lived the hideous gore of war, bloodied trenches and is now living the possibilities of peace. She has dared to trust and she has dared to forgive.

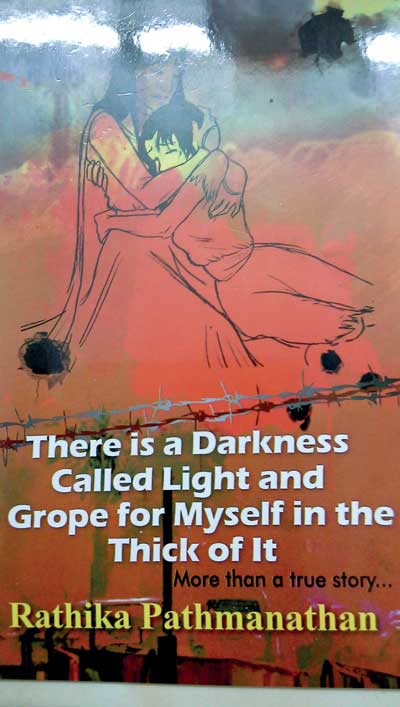

In her book ‘There is a Darkness Called Light and I Grope for Myself in the Thick of It,’ published in English, Sinhala and Tamil,  recounts her days as a teenaged fighter in the LTTE frontlines of the last phase of the war; the nights and days of starvation in the trenches, the excruciating combat training, the loss of family and the new world of Colombo where she arrived for medical treatment for the leg she almost lost.

recounts her days as a teenaged fighter in the LTTE frontlines of the last phase of the war; the nights and days of starvation in the trenches, the excruciating combat training, the loss of family and the new world of Colombo where she arrived for medical treatment for the leg she almost lost.

Seated in the small, sparsely-furnished room she occupies on rent in a remote Sinhala majority suburb in the outer periphery of Colombo, Rathika speaks of wanting to rebuild her life, to study and most of all to actively work towards reconciliation in Sri Lanka, a task she is engaged in at present through her book and as an activist.

At the moment though the challenges of basic existence continues, she is hardly able to bear the rent, medical expenses for her leg looms ahead and the higher education she wants to get remains a dream. The job she held as a telephone operator at the budget taxi centre in Colombo, she had discontinued in order to focus on writing her book and her work bringing communities of north and south together.

She dispassionately examines the bomb scarred right leg which gives her pain and hampers her walk. “According to the doctors I should be doing yet another operation shortly. But I do not think I will get it done. There is nothing much left to cut in this leg. All its nerves are dead,” she states.

She recalls the Thai Pongal day of January 2009 when a mortar fell on it. “I was combing the hair of another female cadre when the bombs fell. I remember looking at the river of blood from my leg and hitting the male LTTE cadre who was taking me to safety, pleading with him to let me die,” she says.

Fate has decreed that she live and that her resilience be turned not to bitterness of racial hate but towards love, wisdom and the appreciation of a universal encompassing of cultures.

She speaks to me in near perfect Sinhalese learnt in her years in Colombo, inquires exuberantly after the health of her landlady of Sinhala ethnicity who comes to the door to offer greetings, and wears a cross, the symbol of Christianity as a pendant. She remains a Hindu but has taken to wearing the cross as a religiously neutral talisman she has taken a liking to.

“I look at my fate as a unique one that led me to be broadminded in my approach to different cultures and people and embrace a change of domicile that I would have never imagined in my wildest dreams ten years ago,” she says with a smile and apologises that she has no cooking facilities in her room to offer me a cup of tea.

She speaks of days of poverty she had known, along with her six siblings, three of them boys, all growing up in different locations in the north after losing her parents.

The possibility of that smile for this still baby-faced girl symbolises hope for post conflict Sri Lanka’s belated steps towards a comprehensive ethnic reconciliation. She has been forced to discontinue her education at 17 years to be a militant against her will. She has known what it was like to shoot to kill. She has known what it was like to resign to the fact that that reciprocal bullet or bomb could be death. She has seen babies float in the murky waves of gunfire carnage.

She has been branded a terrorist in hospital corridors in the Colombo National Hospital and ordered by hospital attendants to fetch her own food despite a crippled state. But Rathika Pathmanathan has proven the Buddhist wisdom that hate does not conquer hate.

“At the last stage of the war, we had so many young Sinhala soldiers who kept on approaching our frontlines and we were mostly all much younger than them. They were just around 200 metres away. We could hardly bring ourselves to shoot at them. Many times we took blind aim and shot knowing it would miss,” says Rathika, sharing her recollections with me and explaining the background to the events that made her write her book.

Her wisdom and her bravery, in both war and peace is astounding.

“We should not be slaves to the heritage of racism given by our elders,” she tells me earnestly and narrates how her relatives, neighbours and friends were shocked at her decision to make a new life in the south.

“They were reacting only from the perspective they knew. I was told not to trust the Sinhalese. I was told that they will destroy me. I did not believe that. Adults told me I was a child and I should listen to them. I refused to listen to them and I have now lived for five years with the Sinhalese and I know I was right in giving trust a chance and I would tell the Sinhalese the same thing,” she says and once again her intelligence and the wonder of her Sinhala language skill impresses me and I am mortified that I cannot respond to her in Tamil.

“I learnt that I could feel sorry for myself and engulf myself in this sorrow or get out of it. After having come to the Colombo National Hospital and making friends with the young girl in the same ward and her family I was very happy. After some time I learnt that children don’t like when their parents share affection with others and that it had nothing to do with ethnicity,” she says, narrating the events that led to the forming of the non-governmental organisation, the Community Reconciliation Centre with Upali Chandrasiri, the father of her hospital ward friend.

The organisation has to date, with minimum funds, and functioning as a community organisation working with different ethnic communities, facilitated many exchange visits between youth of the north and south working with the goal of community-based reconciliation.

The book

The slim volume penned by Rathika Pathmanathan traces her young life, first as an orphan at the age of six having lost her parents to the war and then to a determined teenager to make her life alone through education, and then after recruitment to the LTTE soon after finishing her Ordinary Level examination, to the stage of her being wounded in battle and ensuing surrender to the Government Military at the last phase of the war and subsequent transfer to the National Hospital in Colombo for the injury of her leg.

The book is the evidence of courage of a youth who has insisted on not being corrupted by the stupidity of politicians and warmongers. What is unique about the book is the vicissitude of talent that she displays, to include poetic reflections, showing competency in metaphoric description.

The book begins with 15 poems beginning with ‘We as Children,’ writing from the Tamil perspective, as seen by a child corned to one side of the war.

“Our eyes that gleamed,

Like those of young birds,

Shed tears of blood;

We joined hands to play,

Forming circles in joy.

Then fell scattered, lifeless.”

Her poem ‘Country’ speaks of the misery of civilians of a nation who have to pay for political blindness.

“Behold our country

In flames.

No thought of running,

To escape the fury

Of the bombing…”

The factual reflections of the book begins with the section titled ‘War,’ which begins tracing the last phase of the war from the beginning of 2009 from the time she was in Vattakkachchi preparing for her GCE O/L examination which was the timeframe in which the LTTE was calling for every household to offer at least one member for the movement.

What is unique about the book is that the writer pens frankness that is not caught in the utopian black or whiteness of one absolute truth.

“Mothers kept their children concealed inside the house and warned them direly against venturing out. They did not allow them even to attend school. They were afraid that they would be waylaid and spirited away,” she states in the book. Although recruited by the LTTE against her will and shattering her dreams of higher studies, Rathika acknowledges that she began to feel love and respect for fellow cadres who were sacrificing their lives for a cause as per their belief.

“Though we were forcibly taken, I observed that we were not reminded of our homes when we were with them,” the book states and continues, “Though we did not like it, we had to bear arms and engage in fighting.”

In the section titled ‘The Product of the Training Camp,’ Rathika shares the fear she had of being captured by the Government military forces alive and her resolve to shoot herself. Her recollection of fear based stories she had heard from adults in the north made her want to do this, she states and explains in her book the fact that she and others were victims of their circumstances.

That the Tamil people did not always agree with the LTTE, such as in the decision of conscription and inability of the Tamil people to resist these decisions are cited. She also cites the sympathy that re-flowed to the LTTE movement and helped accelerate recruitment once again, after the graves and monuments of the cadres were destroyed by approaching Government troops.

In reading this book, it is the human factor, the human cost, the human psychology and the abhorrence we should have of killing that is important to be kept in mind, along with the reflection that the role of wise governance should be to govern in order to avoid war.

The battlefield

The battlefield

“Since I joined the Liberation Tigers Movement in the year 2008, I cannot brag that I am a veteran. We stood watch in the jungle day and night. At the initial stages we were assailed with fear. However, when we continued like this, we gradually overcame this fear and we were able to garner courage and a determination to go on.”

In the section ‘The Battlefield,’ Rathika describes the final onslaught of battle and how she, along with the other injured cadres, were permitted to go back home by the LTTE.

She describes Mulliwaikkal, the last location at which the war ended with a realistic description of a war where the intention of both sides is to destroy and in desperation, the intention of the LTTE, to prevent civilians crossing to the military side at any cost.

An excerpt: “Was it by gun shots, artillery shells and aerial bombings that claimed the lives of thousands of civilians? People left their houses and vegetable plots in a hurry and ran with some clothes to save their lives. We arrived in Mulliwaikkal. Now we had only the sea in front of us.”

Rathika describes in the book how she reconnected with her brother, the surrender to the Government military, the overcrowded detention camp, her stay in the Vavuniya Hospital in order to treat her leg and her transfer to the Colombo Hospital and the manifestations of insulting prejudice as well as overwhelming kindness by diverse sections of the Sinhala staff members of the hospital. The book ends with the beginning of the new life that she carved for herself after the discovery of her new South based family members.

Excerpt: “Sometimes I feel elated when I think of my life now and I am proud of myself. Aunty Dr. Vimala, Aunty Dr. Raji, Mr. Upali Chandrasiri, Dr. Sujatha Gamage, Mr. Gamini Ajith and Mr. Ranjith Dissanayake were the people who made it all possible to reach this stage in my life. They helped me beyond any prejudices of ethnicity and religion and loved me like a daughter and guided me all along.”

The last two chapters describes her persistent aim of recovering from memories of war induced orphan-hood and her post war days with Sinhala society and the sum up of the human need for reconciliation.

Excerpt: “After I came to Colombo and started to work among the communities, I acquired an understanding of Sinhalese people and of the world. I developed respect, love for humanity. I came to understand that the Sinhala people were, like us, also suffering. I realised that they shared love and concern for Tamil people. I realised that the war had not been between the Sinhala and Tamil people.”

What this Sri Lankan youth who has emerged a victor of war teaches us through her book is the art of reading the malaise of a country from a human standpoint. And to garner enough strength, after this reading, to try and rectify this malaise with whatever little steps we can take. Rathika Pathmanathan has taken this first step and it is up to us to follow.