Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Tuesday, 30 May 2017 00:05 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

New York: The world’s six largest pension systems will have a joint shortfall of $224 trillion by 2050, imperiling the incomes of future generations and setting the industrialised world up for the biggest pension crisis in history. To alleviate the looming crisis, governments must address the gaps in access to the pensions system and ageing populations as they are the key sources of the widening pension gap.

These are the main findings of the new World Economic Forum report, ‘We’ll Live to 100 – How Can We Afford It?’ released last week, which provides country-specific insights into the challenges being faced at a global level and potential solutions.

“The anticipated increase in longevity and resulting ageing populations is the financial equivalent of climate change,” said Michael Drexler, Head of Financial and Infrastructure Systems at the World Economic Forum. “We must address it now or accept that its adverse consequences will haunt future generations, putting an impossible strain on our children and grandchildren.”

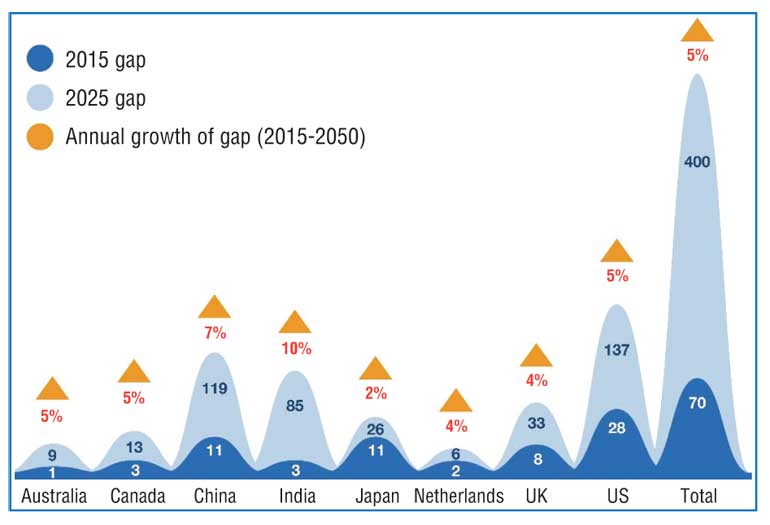

The report is the latest study to calculate the impact of ageing populations on the pension gap in the world’s largest pension markets, which include the United States, United Kingdom, Japan, Netherlands, Canada and Australia. The gap in those markets is the largest in the US, where a current shortfall of $28 trillion is projected to rise to $137 trillion in 2050. The average gap in the six markets combined is calculated to reach $300,000 per person. The total gap for all eight markets in the study (which further includes China and India, which have the world’s largest populations) will reach a total of $400 trillion by 2050. All numbers are summarised in the graph.

The savings gap resembles the amount of money required in each country (including contributions from governments, individuals and employers) to provide each person with a retirement income equal to 70% of their pre-retirement income. Outgoings such as personal savings and tax are often reduced in retirement and targeting 70% of pre-retirement income, in line with OECD guidelines, is a crude guide to provide people with a similar standard of living in retirement as they had before retirement.

For low-income earners the 70% target will not be sufficient and could result in poverty unless savings are increased. The funding gap will continue to grow at a rate higher than the expected economic growth rate, often 4%-5% a year, driven in part by ageing population effects: a growing retiree population who are expected to live longer in retirement.

“The retirement savings challenge is at crisis point and the time to act is now,” said Jacques Goulet, President, Health & Wealth at Mercer, the lead collaborator for this initiative. “There is no one ‘silver bullet’ solution to solve the retirement gap. Individuals need to increase their personal savings and financial literacy, while the private sector and governments should provide programs to support them.”

The report suggests five high priority actions that governments and policy-makers should take to adapt pension systems to address the challenges:

Review normal retirement age to increase in line with life expectancies. For countries where future generations have a life expectancy of over 100, such as the US, UK, Canada and Japan, a real retirement age of at least 70 should become the norm by 2050.

Make saving easy for everyone. A good example is the recent reforms in the UK where 8% of earnings will be automatically contributed to pension savings accounts for each individual from 2019. This initiative to automate the act of saving so far has boosted savings for 22- to 29-year-olds and low-income workers, and is estimated to create $2.5 billion in additional pension savings each year.

Support financial literacy efforts – starting in schools and targeting vulnerable groups. Financial literacy education should be offered throughout people’s careers to raise awareness of the importance of saving. A good case study is the media campaign executed in Singapore for the launch of CPF LIFE, the national annuity scheme that focused on translating a simple message easily understood by the average person.

Provide clear communication on the objective of each pillar of national pension systems and the benefits that will be provided. This would give individuals an understanding of the level of income they can expect from government and mandatory occupational systems and whether they need to accumulate their own individual savings to “top-up” income provided from national systems.

Aggregate and standardise pension data to give citizens a full picture of their financial position. A good example is Denmark, where an online dashboard collates pension information to provide individuals with a holistic view of their different pension savings accounts.

The report emphasises that governments and policy-makers have a central role to play in reforming pension systems to ensure we can adapt to societies where living to 100 is commonplace.

“Because retirement outcomes unfold slowly over decades, emerging problems are very hard to see and are virtually unchangeable once they occur,” said Robert Prince, Co-Chief Investment Officer, Bridgewater Associates and part of the World Economic Forum’s Retirement Investment Systems Reform Project Steering Committee.

“Good outcomes require effective approaches and good decisions applied consistently over decades. Ineffective actions taken over decades will put a weight on society and economies that will be virtually impossible to lift once it occurs. Given ageing populations and increasing lifespans, effective reforms are required now.”

The report was prepared by the World Economic Forum in collaboration with Mercer, a global consulting leader across health, wealth and careers. The Retirement Handbook, detailing 12 case studies, supplements the report and can be downloaded via http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Retirement_Handbook_2017.pdf.

To give the best possible global view, the analysis includes eight countries; the largest six countries in the OECD by pension fund total investment and the two countries with the largest populations. France, Germany and Italy do not fall into the six largest pension systems when based on size of pension assets alone. In France and Germany Defined Benefit liabilities are typically unfunded. In Germany, for example, many employers use book reserves to fund pension obligations (a method whereby internal company assets are delineated for the pension plan and placed on the balance sheet). Norway’s Government Pension Fund Global was not considered a conventional pension plan given its non-contributory nature.

The methodology underlying the size of the pension gap calculation and data sources are detailed in the report.

The analysis assumes that the majority of individuals’ retirement needs will be met by a combination of income from three sources: government-provided pension, employer (public or private sector) pension and individual savings.

The analysis uses publicly available data on the level of funding of government-provided, first-pillar systems and public employee systems, the funding of employer-based systems, and the levels of individual pension savings. The aggregate level of savings across these is compared to expectations of average annual retirement income needs and life expectancies.

The overall level of household debt is not incorporated into the analysis.

The study assumes that current global conventions of retiring between 60 and 70 years of age are maintained and that individuals do not remain in the workplace longer.

For individual savings, it is assumed that retirees will receive income from the mandatory public system and that their income will then need to be “topped up” to provide 70% of pre-retirement income to adequately support them level with individual savings. This 70% income replacement rate target is in line with OECD guidelines.

When considering individual pension assets, the study accounts for the fact that the majority of savings are held by the wealthy. The analysis excludes assets held by the wealthiest 10% based on wealth inequality data provided by the OECD.

Where the mandatory pension system provides an income greater than 70% of a typical final salary, the individual savings gap is assumed to be zero.

The analysis incorporates projections for wage inflation and population growth.