Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday, 18 May 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Kithmina Hewage and

Semini Satarasinghe

Sri Lankan exports, which have been flagging in recent times, gained some much needed relief with the European Union’s (EU) Foreign Affairs Council deciding to grant additional trade preferences to Sri Lanka under its GSP Plus initiative.

By granting this concession, Sri Lanka will now benefit from the full removal of tariffs on Sri Lankan imports into the EU on 66% of tariff lines (approximately 1,200 Sri Lankan products), covering a wide array of products including textiles, small machinery, and fisheries. While gaining GSP Plus is undoubtedly a positive development for Sri Lanka’s economic progress, its impact will provide only temporary relief and policymakers and the private sector should urgently ensure broader economic reforms in order to fully utilise this opportunity.

Sri Lanka’s history with GSP Plus

GSP Plus concessions were initially granted to Sri Lanka in 2005, after the Tsunami. However, in 2010, the EU withdrew Sri Lanka’s preferential access under GSP Plus to the European market due to the Government’s failures in adhering to human rights standards set under the provisions of the scheme.

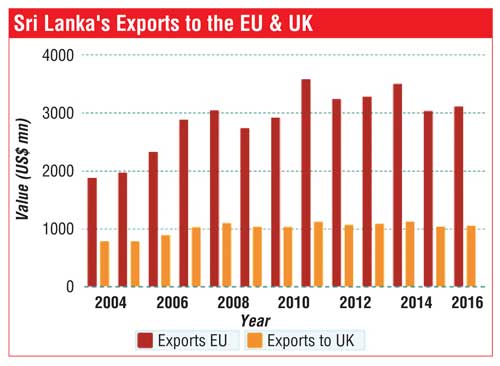

Between 2005 and 2010, under GSP Plus access, Sri Lankan exports to the EU grew on average by 7.96%, notably amidst a decline in consumer demand in Europe due to the financial crisis during 2009 and 2010. Contrastingly, during the 2010-15 period, Sri Lankan exports to the EU grew by a mere 1.02%. The most direct impact was tariffs being reinstated on Sri Lankan imports to the EU, making them uncompetitive compared to similar imports from other developing economies, such as Bangladesh, India, and Vietnam.

The impact was particularly severe on medium sized apparel producers, as they did not possess the technical and financial resources to adequately diversify their export portfolio compared to the larger firms. As a result, with regional competitors such as Bangladesh and Vietnam producing similar products, a significant volume of both domestic and foreign investment relocated to these countries seeking preferential access to the EU market.

Scope for growth

Whilst regaining GSP Plus is a significant achievement for Sri Lanka, both policymakers and the private sector should consider it as simply temporary relief. Gaining tariff-free access to a European market that has seemingly recovered from the 2009 financial crisis and regional economic pressures such as the Greek debt crisis bodes well for improved demand for Sri Lankan goods.

This will especially be a boon to the apparel and fisheries sectors that suffered significantly in recent years and face growing pressures from regional competitors. Other export sectors such as small manufacturing and especially those that have emerged in a post-conflict Sri Lankan economy will also get an opportunity to penetrate the European market.

Temporary relief, not permanent solution

The abovementioned benefits, however, will be restricted to the short term and Sri Lanka should prepare its export sector and the economy overall for the eventuality when these benefits expire. Critically, Sri Lanka will lose GSP Plus concessions once it graduates to upper-middle income level (Gross National Income per capita between $4,306 and $12,475). Currently Sri Lanka’s GNI per capita is $3,800 and will likely achieve upper middle-income status in the near future, estimated to be around 2021.

More concerning, however, are the structural limitations of the Sri Lankan economy that will hinder the ability to fully leverage the benefits of GSP Plus. Crucially, the apparel sector is currently facing significant labour shortages that undermine the ability for the sector to expand sufficiently in a manner that can cater to expected increases in demand.

Similar structural issues such as high para-tariffs and policy instability also reduce the competitiveness of the Sri Lankan economy. Whereas Sri Lanka’s competitors such as Bangladesh and Vietnam are embarking on large-scale economic reform agendas, Sri Lanka’s relative reticence restricts its potential for growth.

In addition to these structural challenges, Sri Lanka should also be cognisant of the impact of Brexit on leveraging GSP Plus. Since the referendum and the subsequent triggering of Article 50, the United Kingdom is scheduled to leave the European Union on 29 March 2019. Worryingly for Sri Lanka, approximately 30% of Sri Lanka’s exports to the EU are to the UK.

Sri Lankan exports will no longer qualify for preferential access to the UK once it leaves the EU, unless a similar arrangement is negotiated directly between Sri Lanka and the UK. Therefore, Sri Lanka should prepare to face an economic shock, at least temporarily, to its export sector once the UK officially leaves the EU.

Managing the future

A combination of structural failures, protectionist economic policies, and external factors has led to Sri Lanka’s export sector performance diminish in recent years and fail to fully realise its potential. The withdrawal of GSP Plus in 2010 was especially damaging since the country was not adequately prepared to compensate for its loss in relative competitiveness in the European market. Therefore, regaining GSP Plus is a much welcome development for the economy.

These benefits, however, are short-lived and the country will fail to fully leverage the opportunity afforded by GSP Plus for improved trade in the future unless significant reforms are undertaken to address structural weaknesses in the economy.

Such reforms need to focus on promoting growth, tackling demographic issues, fostering an efficient public taxation system and improving the labour market. Liberalising product and service markets would further encourage private enterprises to participate in economic activities. In the meantime, the private sector should consider this as temporary relief and use the opportunity to diversify its product basket while also looking towards diversifying its export destinations.

Preferential access granted through GSP Plus provides Sri Lankan exporters an advantage in sectors that the country may not traditionally trade. Therefore, the risk of diversification is lower and the reward of exploring new opportunities for exports will be much higher.

Moreover, the most dynamic economic growth is expected to occur in countries like India, China, and other East Asian countries in the ASEAN region. Therefore, Sri Lanka can no longer depend solely on the European and US markets and would be better placed by reorienting towards emerging economies in Asia and the Middle East.

(Kithmina Hewage is a Research Officer and Semini Satarasinghe is a Project Intern at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS). To view this article online and to share your comments, visit the IPS Blog ‘Talking Economics’ - http://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/)