Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Tuesday, 21 March 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The attire of the Muslim woman has perhaps never been under greater scrutiny than it is today. This obsession with the dress code of Muslim women is unhealthy; it does bodes well neither for the advancement of freedom nor women’s empowerment

The attire of the Muslim woman has perhaps never been under greater scrutiny than it is today. This obsession with the dress code of Muslim women is unhealthy; it does bodes well neither for the advancement of freedom nor women’s empowerment

By Ayesha Zuhair

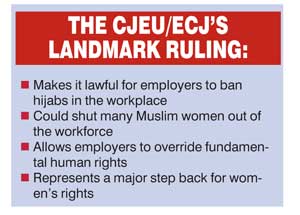

A mere day prior to the Ides of March, on Tuesday 14 March, Europe’s highest court – the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU/ECJ) – delivered a shock judgement giving employers the right to prohibit Islamic headscarves in the workplace.

In its ruling, the Luxembourg-based court held that employers who adopt a policy of ‘neutrality’ and bar the display of all religious and political insignia are not in violation of the EU’s anti-discriminatory laws.

The ECJ decreed that: “An internal rule of an undertaking which prohibits the visible wearing of any political, philosophical or religious sign does not constitute direct discrimination.” This, in essence, conferred upon employers the right to ban women from wearing headscarves at work. It was the ECJ’s first decision of its kind on the issue of religious attire, and came within a week of International Women’s Day on 8 March.

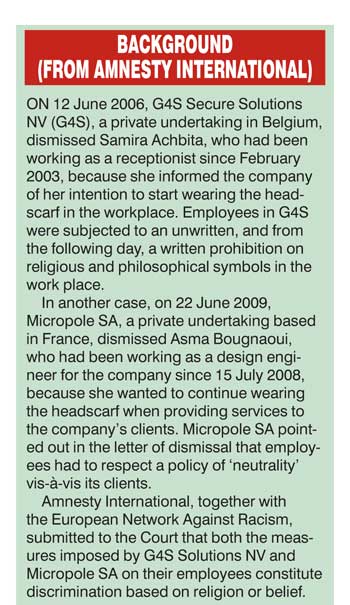

The top court’s judgement – which sets an EU-wide precedent – was delivered in the cases of two Muslim women in Belgium and France who had been dismissed from their respective workplaces for refusing to remove their hijabs.

EU judges held that a prohibition must be in line with an organisation’s established and consistent policy of projecting a ‘neutral’ image. The joint verdict is therefore not a blanket ban on Islamic headscarves; it is equally applicable to manifestations of all religious beliefs such as Sikh turbans, Christian crucifixes/crosses, and Jewish skullcaps.

The ECJ decision to bar religious symbols in the workplace disfavours all religious communities but worsens discrimination against Muslim women in particular, who will be disproportionately affected by the ruling. So it is a direct attack on the Islamic dress code adhered to by many Muslim women. And with it, ‘Et tu Brute?’ has become ‘Et tu ECJ?’

In the first case, the ECJ ruled that a Belgian firm was entitled to dismiss an employee who had begun wearing the Islamic headscarf to work on the grounds that it was contrary to company rules on appearance which required employees to ‘dress neutrally’.

In the second case, where a French woman was fired for refusing to remove her headscarf following a customer’s complaint, the court re-affirmed the position it took in the first case. The judges held that the employee’s dismissal would be lawful if it was not in compliance with an internal company rule prohibiting the visible wearing of political, philosophical or religious beliefs.

In other words, the only condition for the dismissals to be valid is for the firm to have followed a written or unwritten policy of so-called ‘neutrality’. As a result, it is very likely that at least some European companies will now introduce rules that explicitly prohibit the display of religious insignia.

Under the pretext of recognising a firm’s right to ‘image neutrality’, the court’s ruling curtails religious freedom, and feeds into (and was probably also fed by) Islamophobia which is growing in many parts of the world. It places a barrier stymieing the entry of Muslim women who consider the hijab as a core part of their belief system into the workforce.

Aren’t Muslim women being indirectly told to abandon their way of life? Is it not unfair for them to be asked to choose between their faith and gainful employment? Freedom of religion includes the freedom to manifest that belief in public, as acknowledged in the official ECJ statement on the ruling. So it is indeed strange to suggest that a person’s religious identity should be altogether cast aside upon taking up employment. For the Muslim woman who chooses to cover because of a deeply-felt religious conviction, this is particularly difficult and problematic.

It is also problematic because the restrictions placed on religious expression is at serious odds with the principles of freedom, justice and equality. It is worrying that a court which purports to champion justice and freedom has placed clear limits to an individual’s right to exercise her or his religious freedom. The ruling puts an employer’s desire to project ‘neutrality’ over and above the right to religious freedom. The court has thus made it lawful for employers to violate the fundamental human right to freedom of religion. Is this is not a retreat to the dark ages?

John Dalhuisen, Director of Amnesty International’s Europe and Central Asia programme, points out that the ruling will give “greater leeway to employers to discriminate against women – and men – on the grounds of religious belief. At a time when identity and appearance has become a political battleground, people need more protection against prejudice, not less”.

The joint judgement though is framed in a ‘neutral’ language directly targets Muslim women in hijab; this is exactly why the European far right is delighted with the decision. It will do nothing to promote social cohesion and multiculturalism in Europe. On the contrary, it will further marginalise and alienate Muslims in Europe by possibly preventing scores of Muslim women from entering the workforce. This will naturally result in greater resentment among all those who wish to practice their faith without fear.

The attire of the Muslim woman has perhaps never been under greater scrutiny than it is today. This obsession with the dress code of Muslim women is unhealthy; it does bodes well neither for the advancement of freedom nor women’s empowerment.

European civilisation has for long prided itself on individual freedom, proclaiming that individual liberty is sacrosanct. But the apparent discomfort in accommodating expressions of faith only signals its growing intolerance and hypocrisy. So long as fear and hostility towards the ‘other’ is dominant in its psyche, European society cannot claim to be truly enlightened or liberal. That can only come with a genuine willingness to accommodate and indeed celebrate differences; certainly not by taking discreet steps towards cultural assimilation. It is now left to the respective governments in Europe and their national courts to reverse the regression by stepping in to protect the fundamental rights of its citizenry.