Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Wednesday, 26 April 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By C.R. de Silva

By C.R. de Silva

On 6 and 7 April, Sri Lanka’s ‘First National Symposium to Develop a National Export Strategy’ (NES) was held under the auspices of the responsible Ministry and the Export Development Board. The declared, very laudable objective of the Government at this event was to kick off the preparation of such a national Plan for the next export growth cycle of Sri Lanka.

This first symposium will unveil the design process for the NES and provide a platform for public and private stakeholders to discuss their strategic vision for Sri Lanka’s export growth; confirm the export performance diagnostics as well as the main strategic orientations for the NES, including identifying the priority sectors and selected trade functions. Thereafter, discussions will take place countrywide to define specific sector level action plans leading to formulation of the National Export Strategy. The gestation period for the NES is likely to be four years.

The Government is, therefore, at the very initial design process stage of formulating the path to progress of a National Export Strategy at this time, while being also committed to a policy of free trade, and also meanwhile, simultaneously negotiating Free Trade Agreements (according to high-level official announcements) with at least three countries, namely China, Singapore and India, with many more FTAs with other countries in the prospective, but confirmed, pipeline.

In the concurrent absence of also a national plan or industrialisation strategy for Sri Lanka, the obvious issue arises whether, given the current lack of a guiding vision based on a national industrialisation as well as an export development strategy, is it premature as well as inadvisable, to enter into Free Trade Agreements in the next several months?

It is well known to all successful practitioners of national development strategy, that between the initiation of discussions leading to the formulation of national plans and overall strategies on the one hand, and the timing of their maturity at a final implementation stage, and the realisation of objectives of such plans on the ground, long, multi-year lead times are a pre-requisite for ultimate success – in this instance, estimated to be four years. Where interaction with stakeholders at political, business, provincial and district levels are also important, and contemplated as in this case, realistic lead times become inevitably more prolonged to achieve any sort of operational consensus and NES finality.

There is also no recorded evidence in recent economic history, that development processes, whether of national program or investment project dimensions, can be telescoped (or dovetailed) timewise into each other to expedite instant maturity or reach quick success for their declared objectives or designated national ends.

As the responsible Minister for Development Strategies has written on the occasion of the above Symposium, “The Government has taken the challenge on board and is working on a multi-faceted economic policy framework which will integrate to create an enabling environment for long-term growth and the benefits will trickle down to all levels of society, building long-term sustainability and economic prosperity for all.”

While the choice of “trickle down” as a development strategy is indeed unfortunate, the overriding issue being addressed in this essay, nevertheless, remains: Is Sri Lanka ready for Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) at this time?

“The average annual growth of exports in developing Asia has also declined sharply from 11+% to under 5% in 2000-2015, reflecting a fragile post-global financial crisis environment of weak import demand in advanced economies, moderating growth, re-balancing the economy in China and the rise of protectionism. Meanwhile, Sri Lanka’s average annual growth rate of exports is at half the average growth for other developing Asian countries” – a direct reflection of the poorly developed domestic industrial base, to manufacture exportable products.

“Several measures are needed in Sri Lanka to promote the Small and Medium Enterprises (SME) to exploit their potential role in the current migration of Chinese labour-intensive global value chain (GVC) stages to other countries, as China automates its technology, e.g. prioritising the financing of SMEs by improving financial literacy; removing language barriers to ensure SME access to GVCs; and forming SME ‘clusters’ stimulated by the necessary incentives and infrastructure facilities.”

Before further liberalising trade through FTAs, “Sri Lanka should improve job productivity through labour market reforms; prioritise the upgrading of tertiary-level engineering skills; invest in digital as well as physical infrastructure; enhance surveillance of non-tariff imports; and improve the investment climate for domestic investment and FDI…Also, ratify the WTO’s Trade Facilitation Agreement, which promotes investment in trade infrastructure, to reduce trading costs and improve competitiveness; engage with mega regional FTAs like the proposed RCEP (a multi-country trading agreement, referred to earlier, and led by China) to explore new markets; and promote good regulatory practices” (excerpts extracted from a speech by Dr G. Wignaraja, Advisor, Chief Economist’s Office, ADB, Manila, at L. Kadirgamar Institute, February 2017).

The writer’s understanding of the bottom line the ADB expert is conveying successfully is that it is premature for Sri Lanka to so proactively and speedily enter into various bilateral FTAs with more industrialised countries, without developing a viable industrial base enabling competitive export product manufactures, enabled by first eliminating structural problems detailed above, as far as possible.

An important issue that arises is whether Sri Lanka has prioritised sector investments, and already put in place adequate international trade infrastructure, e.g. smoothly functioning customs clearance, port facilities consistent with peak demand and similar export/import logistics support, well before entering into numerous FTAs to help boost export trade?

Has Sri Lanka benefited from the World Bank’s Trade Facilitation Support Program and the WTO’s Trade Facilitation Agreement, to help lower trading costs and improve export competitiveness? Studies have proved that investment in such trade infrastructure has a strong and positive impact on trade flows, which are clearly an engine of economic growth and also revenue enhancement, when international trade balances are positive, which has proven not to be the case with Sri Lanka at this time or in the recent past.

Admittedly, infrastructure constraints in Sri Lanka are not only experienced at the border, but in the capital city at most hours now, since many thousands of vehicles compete for road space designed mostly, possibly one hundred or so years ago, when there were hardly any vehicles on the road, compared to the present days’ huge numbers resulting in constant congestion, which may soon resemble a slow-motion parking lot, like in Bangkok at one time.

Adequate energy generation especially at times of drought are no better; together indicating that domestic infrastructure is clearly lagging behind international trade infrastructure – a mismatch described by experts as hurting a country’s development prospects, undermining its potential to enhance domestic commerce and also export/import trade. The above circumstances in Sri Lanka additionally results in a reallocation of FDI away from such countries as ours with relatively poor domestic infrastructure, since investors explore locations where it is cheaper to effectively manufacture goods as well as provide services.

Obviously, these issues involve a range of possible trade-offs on what investments to prioritise – these include quality versus quantity, enhanced maintenance or new investments, financing infrastructure with user fees versus public subsidies or universality of services compared to cost efficiency. Another open issue which may not have been addressed in Sri Lanka is the impact of imminent trade reforms through FTAs on domestic labour markets, mostly in the SME sector, especially since employment of the largest number is always a hot economic issue with foreseeable public disturbances and social unrest. (Marcelo Olarreaga, Professor of Economics at University of Geneva, ‘Why poor countries should invest first in national trade infrastructure’).

Researchers have identified a “laborious process, which takes nearly five years to complete, in facilitating trademark registration in Sri Lanka, and has resulted in fewer local brands; these bureaucratic delays are reported to have cost billions of rupees to the export community. This combined with the current, long delay in the local ‘road-block’ (despite Cabinet approval and an authorised Rs. 100 million budget), towards Sri Lanka joining an international club of 114 countries known as The Madrid Protocol – a centralised global mechanism established in 1989 for registering domestic trademarks internationally - was the main reason why Sri Lanka had few famous international brands, like Ceylon Cinnamon, Damro and some garment brands”.

Research investigations have discovered that the National International Property Office (NIPO) takes three to five years to register trademark applications, significantly limiting Sri Lanka’s ability to benefit from The Madrid Protocol, which our country has still to join, and therefore, faring poorly at 14% (of applications registered), compared to other middle-income countries like Vietnam, Philippines and Turkey at 50% of such registered applications. Consequently, local exporters have to register trademarks individually in every single destination of export at considerable cost and in ’nightmare circumstances’, persuading the Export Development Board (EDB) to now bear the exporters’ high cost of legal fees and other expenditures attendant on the foreign registration process.

Quantifiable export losses are in the billions of rupees, but unquantifiable losses from other countries competing with their own brands are much greater. (Extracted directly from Verite Research conclusions at a Colombo seminar on 2 February). Needless to repeat, none of these constraints have mitigated the political rush to conclude FTAs with several such trade-competing countries as quickly as possible, with more unquantifiable and widespread adverse consequences.

Major reasons why Sri Lanka has experienced an export slowdown in recent years compared to its Asian peers is due to the latter, now fast growing economies, diligently developing new lines of business and thereby diversifying their export base; becoming technologically more advanced and graduating, for example, from production of garments, brand name apparel, rubber and leather goods to first electronics, and then machinery production. While low-end tourism is domestically a success, It is essential, therefore, that Sri Lanka advance in its technology and compete first even with lower GDP economies in primary manufactured products for export. (See the writer’s ‘New Technology Revolution and why Sri Lanka has fallen behind,’ Daily FT, 3 April).

Speaking at the recent National Symposium to develop a National Export Strategy, funded by the European Union, its delegate stated that “since the 1990s, Sri Lanka’s export basket has not changed much, while her global market share has fallen…diversification is a key to export success; as much as one-half of export revenues was from tea, rubber, the textile and garment sector now for many years…and only about 5% of local companies engage in the export trade”. Only 10-15 businesses dominated the textile and garment export sector, accounting for close to $ 5 billion in traditional exports. Now, labour availability constraints are starting to affect this industry adversely – though garments are a mainstay of current export income.

The technological complexity of many modern, capital-intensive, sophisticated end-products (like automobiles, machinery and airliners) requires the production and procurement of parts and components across national borders through global value chains, open to participation by developing countries which have achieved a higher quantum of technical know-how and a greater production complexity, like India and Singapore, potential FTA partners of Sri Lanka. Professor Ricardo Hausman of Harvard University’s Kennedy School, from whose speech at BMICH in late-January, 2017 these arguments are summarised, went to the extent of making the point that “a country is in fact a collection of technologies, which determine the extent to which economic development takes place”.

The Asian examples of Vietnam and Thailand (another future FTA partner of Sri Lanka), are noteworthy. While Sri Lanka still exports apparel, manpower, tea and rubber, Vietnam has considerably diversified its export range, while Thailand manufactures electronics and vehicles for export. Like in Korea earlier, overseas Chinese returned home, bringing skills and know how that jump-started the now liberalised Chinese economy. There is no recent historical evidence yet to suggest that a similar reverse brain-drain can play out in this country any time soon, for many reasons outside the purview of this essay. While FDI is critical for technology absorption, at barely one half of one percent of Sri Lanka’s GDP in 2016, it contrasts with Singapore at a ‘staggering’ 15% of GDP – another FTA partner of our country – signifying a strong correlation between the level of available technology and FDI, eventually a chicken and egg conundrum!

Sri Lanka’s desirable shift to export and investment-led growth, also requires the establishment of a robust R&D mechanism, led by a national policy, including specific strategies for targeting and assisting promising start-ups, an early initiative in Korea’s development program. Today, universities, public research agencies and businesses have disconnected R&D initiatives, not driven to achieve economically viable goals nor targeting an economically measured output, in the absence of a national R&D vision. Sri Lanka’s expenditure on R&D is also the lowest in this Region at a meagre 0.16% of GDP in 2010, with no appreciable rise until now, mostly targeted at academic goals.

Universities in Sri Lanka are not empowered to earn patents from publicly funded R&D, are inhibited by absence of required lab facilities and a lack of private sector coordination resulting in low collaboration with industry. Also, industry leaders believe lack of entrepreneurial spirit among academics and low commercialisation potential of University research are key deterrents to private sector R&D investment in academia. This view holds that our Universities ‘have calcified’ into teaching shops, which only either do consultancy work for industry or offer promising students for employment.

A World Bank study also found that unlike industrialised countries like Korea or even India, Sri Lankan companies “lack the critical mass to invest in research”, with less than 100 local businesses having the required capability. The same World Bank report has estimated that less than 50% of local university academics have doctorates, with only one-third of them in management sciences. Therefore, a Government policy establishing a national platform is essential for industrial start-ups to become viable business enterprises, and “will be at the core of Sri Lanka’s growth prospects” (Rooting for R&D, recent FT Editorial).

Industry entrepreneurs have complained that following the alleged first bond scam in February 2015, when the Central Bank accepted a bid for a 30-year bond at an exorbitant 12% interest rate, commercial banks also steadily raised their average lending rates for investment from about 6.5% then, reaching around 12% per annum by end-2016, subject to an additional profit margin of another 1-2%. This development effectively meant a 93% increase in the interest rate component of any loan for investment, operating as a clear disincentive to entrepreneurs in manufacturing, already burdened with high electricity charges, higher indirect taxes and increased employee remuneration.

Local commercial bank loan rates compare unfavourably with India at 10% and Bangladesh with an incentive 7% rate for export industrial investment, demonstrating the Government’s commitment. The prognosis is that a free trade policy with cheap imports flooding the country will lead to the closure of many local industries, leaving a trail of loan defaults (Daily FT, 20 April, page 11).

The foregoing conveys the message that “the strategic aspects for developing a national export system, which supports innovation and entrepreneurship”, (which go hand in hand with a vibrant industrial base and technology development), to “commercialise high-value products for export” at a competitive level, should be put in place well before the further liberalisation of trade. The stimulation of innovation and entrepreneurship (long neglected by successive governments), takes long lead times to mature and succeed, and should be originated many years earlier, well ahead of trade policy liberalisation.

During that transformational process, with the aim of becoming a member of ‘global value chains’, the creation of a modern digital economy is a key aspect. In Korea, at this early development stage, promising industrial innovation and entrepreneurship was actively encouraged by the government by establishing early dedicated financing agencies with repeated World Bank loans, in the drive for a viable industrial export economy.

Unfortunately, “the nascent digital industry with great export potential” in Sri Lanka, has been seriously hampered by IMF recommended, recently increased VAT applicable to telecom services (including Broad Band), which will effectively slowdown that industry’s quest as a business process outsourcing (BPO) destination, hurting the growth of rising ICT export revenues. These regressive indirect taxes have also caused cell phone charges to almost double recently, acting to erode just declared Presidential exhortation “empowering youth to get connected with the agriculture export trade, using mobile phones and the internet, instead of continuing with traditional agriculture – and to give it a facelift by using cutting-edge technology” (Colombo page, 11 April 2017). Political rhetoric unaccompanied by policy support leads nowhere good!

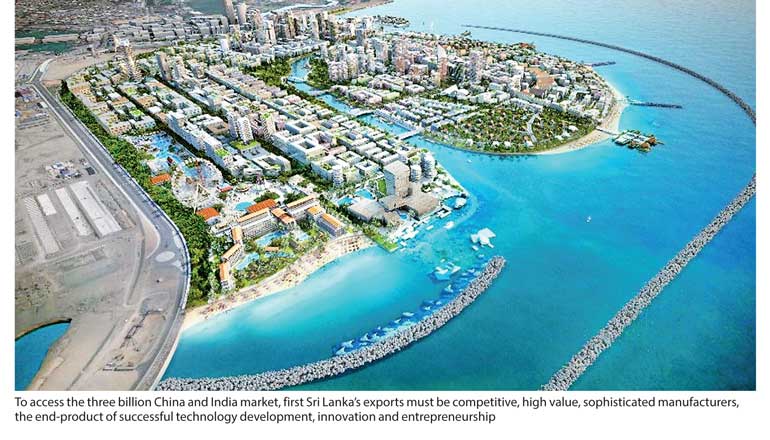

In summary, to access the three billion China and India market, first Sri Lanka’s exports must be competitive, high value, sophisticated manufacturers, the end-product of successful technology development, innovation and entrepreneurship – these transformative changes cannot happen overnight, and simultaneously with trade liberalisation, both efforts starting in the same year. (‘Strategic Brainstorming on Innovation & Entrepreneurship,’ Daily FT news report, 3 March).