Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Thursday, 25 June 2015 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Mansi Kumarasiri and Vijay Nagaraj for the Centre for Poverty Analysis (CEPA)

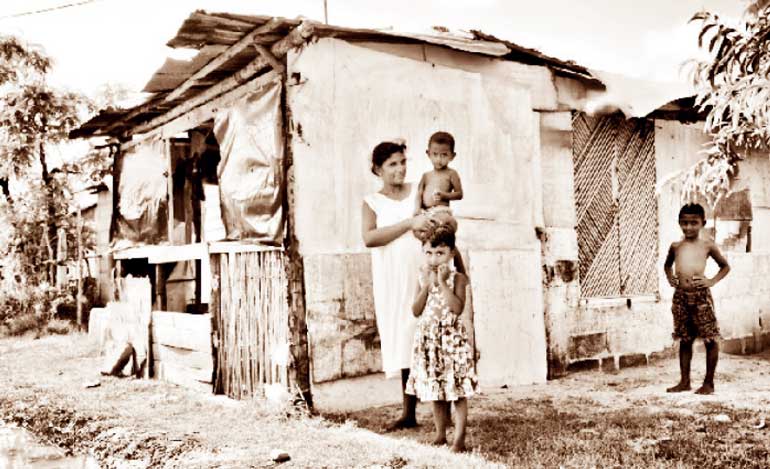

Sri Lanka has a significant policy history in the area of social housing. Since 1948, significant continuities and changes are evident in housing policy in urban areas, which also include environmental and habitat improvement measures as well as community-based participatory approaches.

Policy measures have spanned ‘aided self-help’ to ‘self-help’ to ‘sites and services’ and ‘in-situ upgradation’ approaches to relocation and real estate market-oriented densification strategies. Apart from the commitment and orientation of the political leadership, donors and development agencies and globally dominant ideological orientations have also influenced housing policy.

In addition there have been multiple public institutions engaged with the issue, which has also created significant challenges. The recent post-war moves by the Urban Development Authority in Colombo to relocate under-served settlements into high-rises has raised many questions regarding the basis of policy choices, citizens’ rights and entitlements, and State responsibility in relation to both the outcomes and the process by which the right to housing of the working class poor can be safeguarded.

At the 35th sessions of the United Nations General Assembly in 1980, at the initiative of then Prime Minister R. Premadasa, Sri Lanka mobilised support from several other countries and successfully moved a resolution that reaffirmed “adequate shelter and services as a basic human right.” The same resolution also called for an international year of shelter, which was duly observed in 1987.

In the ebb and flow of Sri Lankan housing policy it is the erosion and loss of a rights-based approach that is most keenly felt by the urban poor today. Once a global champion of housing as a right, policy in Sri Lanka has steadily tended towards adopting an approach that has viewed housing increasingly in terms of an economic asset. This has also meant that housing programs have de-emphasised social mobilisation of communities and reduce them to beneficiaries.

In urban areas, especially in the Western Province that has a large concentration of communities in poverty, upgrading housing with a strong emphasis on people’s participation has made way for one-size fits all high-rise solutions. A focus on freeing up ‘prime land’ land for financial returns i.e., creating real estate, has led to mass forced relocations of poor communities into high-maintenance structures. Apart from serious social and economic consequences for those affected, it has also left State agencies like the Urban Development Authority (UDA) with responsibilities and costs that they are not geared to meet.

A return to a rights-based approach to housing for the urban poor implies, firstly, placing people and not land as a financial commodity at the centre of policy and avoid splitting the social and economic value of land. Secondly, it entails enabling and empowering local authorities and grassroots structures—like in the case of the Million Housing Programme—to play a central role in driving policy.

Thirdly, a rights-based approach also means recognising the agency and capacity of the urban poor—research world over has shown that they invest considerably in incrementally improving their housing—and not reducing them to ‘slum dwellers’ with ‘dangerous cultures’. A fourth crucial aspect of a rights-based approach is to ensure protection from forced evictions, minimise relocation and ensure full respect for all rights if relocation is essential.

But a return to a rights-based approach is not possible without addressing other critical institutional bottlenecks. The multiplicity of institutions, overlapping mandates and duplication has serious adverse implications in terms of planning, resource allocation, and also final outcomes. Strengthening institutional autonomy while enabling more transparent and accountable functioning and building a stronger culture of learning from experience is also critical.

Over the years, in the context of the housing for the poor, rights has been reduced to an empty slogan or narrowly understood in terms of the market. Sri Lanka’s own political history underlines that the right to housing is about the State’s fundamental obligation to its citizens to ensure a decent quality of life.

This National Housing Week is a good time to re-affirm a rights-based approach to housing and underline that the State does not always know best, after all people have built so many more houses than the State.