Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Saturday, 19 November 2016 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Amantha Perera

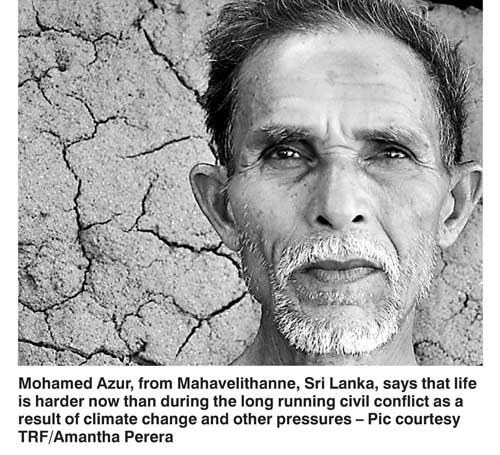

Mahavelithanne (Thomson Reuters Foundation): In the last quarter century, Mohamed  Azur fled his home three times as civil war raged around him, returning when the fighting subsided for a time.

Azur fled his home three times as civil war raged around him, returning when the fighting subsided for a time.

“Life was not hard, if you knew how to avoid the guns and the bullets. There was enough land, water and everything else for everyone here,” said the 62-year-old, standing on the doorstep of his small mud hut covered with tin-sheet roofing.

But since Sri Lanka’s long civil war ended in 2009, this remote hamlet in north-central Polonnaruwa District finds itself facing vexing new worries: more extreme weather linked to climate change, and shortages of both land and water.

Like many isolated villages in Sri Lanka, Mahavelithanne, about 300 km from the capital Colombo, relies on agriculture and little else.

From the mid-1960s, successive governments brought in poor families from outside areas, gave them free land to farm, and provided irrigated water through a system of reservoirs and canals, under a national development programme.

The plan worked until the mid-1990s, when the raging civil war in the region put a halt to development. Many people like Azur spent years displaced.

Since 2009, however, after the end of the war, families forced to flee by the conflict have been returning and in turn raising children of their own. That is putting pressure on local resources, Azur said.

“Because families are becoming larger, there is more demand for land, (and) because people are staying on and cultivating the land, there is more demand for water,” he said.

Floods and drought

Equally troubling, returned farmers have discovered that, in the three decades they were away, rainfall patterns have changed.

“There will be floods and then there will be long bouts of dry weather. Right now we have gone without any substantial rain for over six months,” Harsha Bandara, the top Government official for Welikanda Division, under which Mahavelithanne falls, told the Thomson Reuters Foundation in October.

The region’s water distribution network and agriculture management were not keeping step with the shifting climate patterns, he said.

“For example, we need people to be much more careful in ground water extraction - even consider what time of the day is optimal to use the pumps,” he said. “That knowledge is lacking. Instead what we have is people using industrial-level pumps to dig deeper and deeper, even down to the bedrock.”

Though rain late last month broke the long dry spell, over 35,000 people in Welikanda struggled with the drought, many surviving on water trucked in from outside.

Bandara also said that since the end of the war, large numbers of cattle have also been brought into the region by dairy companies, increasing the demands on resources.

And “there are large herds of elephants in the jungles in this region and now they keep coming into villages more often, looking for water and food,” he said. “On top of that, when the soil is dry, the electric fence set up to prevent such incursions malfunctions.”

The Government’s Disaster Management Centre said that more than 870,000 people had been hit by the drought island-wide.

Crowded town

The struggle for water and land is far more chronic in Kattankudi, a small town about 100 km east of Mahavelithanne but more urbanised because it straddles the main road.

M.M. Shafi, Secretary of the Kattankudi Urban Council, said that at least 500 families had returned to the town since 2009. Today, over 53,000 residents live packed into an area of under 4 square kilometres, at a population density 20 times the national average.

“We have big problems when it comes to water, flood protection and even garbage disposal,” Shafi said. During the conflict, concerns were manageable since the population did not grow and demands were minimal, he said.

“Now we have businesses coming up all the time, farmers looking for more land and water, and there is no way we can provide that,” he said.

Paddy rice farmer Wickrama Rajapaksa, who chairs the Sinhapura village farmers’ association village in Welikanda, said the new challenges are a disappointment for those who had hoped to return after the war and build a good life.

“During the war, most of us who were here just wanted survive. Now, we want to prosper, be rich. But to do that, first we need to deal with all these natural changes in rain, temperature and river water,” he said. “That is harder than running away from bullets.”