Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Thursday, 10 September 2015 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

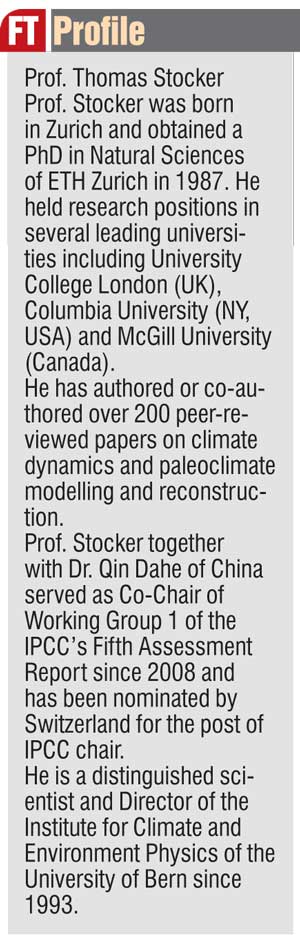

Ahead of the 42nd session of the United Nation’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), nominee for the post of IPCC Chair Prof. Thomas Stocker visited Sri Lanka to discuss matters pertaining to climate change with the relevant authorities and climate change representatives.

Switzerland nominated Prof. Stocker for the post of chair of the IPCC which will elect its new bureau during its 42nd session to be held in Dubrovnik, Croatia from 5 to 9 October.

During his visit to Colombo last week, Prof. Stocker together with Professor of Chemical and Process Engineering at the University of Moratuwa and the Project Director of COSTI (Coordinating Secretariat for Science, Technology and Innovation) Prof. Ajith De Alwis sat down with the Daily FT to discuss climate change while highlighting key areas in which progress had already been made.

Following are excerpts:

By Malik Gunatilleke

Q: What is the mandate of the IPCC?

A: The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was founded in 1988 in preparation for the first Rio Summit. Governments wished to receive information on what we knew about climate change and the uncertainties, impacts, future impacts of various climate change scenarios as well as the socio-economic points and issues associated with climate change. Two years later the IPCC released its first assessment report and in 1992 was the first Rio Summit which produced the framework convention on climate change.

The IPCC was then requested by the governments to provide objective and transparent scientific assessments on what we know about climate change on a periodic basis. It has delivered five successive assessment reports and a series of special reports on focussed topics. We are carrying out this work with a high level of policy awareness and we have to be, as per our procedures, policy relevant but at the same time not policy prescriptive. The IPCC never advocates one scenario over another. Once the policy makers have decided on a target, we can say which of the scenarios are compatible with that target.

Q: What will your objectives be if you are elected the Chair of the IPCC?

A: I have three main objectives that I believe are determinant to the future relevance and success of the IPCC. The first priority is communication. This is why the parties to the convention have declared that climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our time. We need to communicate the scientific assessments in a clear and understandable language to reach not only the policy makers but the public too. I have contributed in the last cycle to bring this communication to a new level of understanding by proposing ‘headline statements’.

Working Group 1 was the only group that supplemented its summary for policy makers with headline statements which are simple, non-technical assertions; sentences that the media can actually quote without modification because they do not contain numbers or technical jargon. Now the statement “human influence on the climate system is clear” is a consensus statement agreed upon by all governments participating in the IPCC. If you read the 19 headline statements of our summary for policy makers in sequence, you get the entire narrative of our 1532-page report; so it’s a super distillation of the scientific content of this report.

Communication should also be a permanent activity of the IPCC. Traditionally, the IPCC has only communicated towards the end of an assessment period. I think after five assessment reports we have enough information to be able to make this a continuous activity. My third point on communication relates to who really carries out the communication. Even though I acknowledge that the Chair holds a special position in representing the activity of the IPCC, I am personally convinced that the best ambassadors of climate change are the scientists themselves. We need to recruit and empower scientists from all countries to become ambassadors of their findings.

The second priority is motivated by my observation that the discussion on climate change has become more political. Finding solutions to the problem is political as we have to find the best methods of implementation within a country. However, I am convinced that the scientific assessment informing these processes must remain scientific. This does not mean that I am building a wall between the policy makers and the scientists. I believe in the power of a dialogue between the policy makers, who are the primary receivers of our information, and the scientists, but we need to be aware of the mutual responsibilities both parties have.

The final priority is the most important one and that is the regionalisation of climate assessment information. We need to provide policy makers with information that really drills down to the region. What does climate change really mean for those specific regions?

Q: What is your mission here in Sri Lanka?

A: As you might already know, I’m running for the position of Chair for the IPCC. It’s important to visit countries in person to discuss with ministries the priorities of the IPCC that would guarantee its future success in the next five to seven years. The two most important factors of visiting any country is the exposure and vulnerability of the country to climate change and the challenges that derive from that exposure as well as the potential to involve the scientific community of that country in the next assessment cycle. I’m happy to be in Sri Lanka to discuss with both the Ministry of Environment and the Foreign Ministry my plans and priorities to make sure the Government entrusts me with this position. This is my last of six tours in which I visited all six regions. I did Asia in two legs, Southeast Asia and now Central Asia.

Q: How important is Central Asia in the discussion on climate change and what are the challenges we face as a region?

A: Extremely important. Asia and Southeast Asia have three major challenges in terms of climate change. One is the challenge of sea level rise. We have more than two dozen countries that have coastal settlements and millions of people are directly affected by sea level rise.

The second challenge relates to the water resources – another challenge that directly affects the livelihoods of people and eco-systems.

The third challenge is extreme events which is something that greatly concerns this region as well.

Q (Prof. De Alwis): How important is it to encourage young scientists and involve regional scientists in assessing climate change?

A: I would like to encourage countries to carry out national assessments. I would like to see activities in which data on temperature precipitation, extreme events, specific impacts on eco-systems, water availability in the Dry Zones, are collected. I think the capacity is absolutely present in every country. I think the key agency here is the national agency on meteorology. I believe that through the climate service network there is a great opportunity to raise the awareness within the scientific community and in order to motivate a new generation of scientists to contribute. National assessments would provide to IPCC the information that usually we are unable to access because we simply don’t know about them.

At the moment we have regional scientists but they don’t necessarily understand the climatic intricacies of each and every country that belongs to the region. I think national assessments will aid us in two ways – firstly, to mobilise people to think about climate change in your country which is active capacity building from within and secondly, you have made the information available for inclusion in IPCC. The IPCC has a global view of the problem but we would now like to close this gap within the organisation.

Q: What role does a country like Sri Lanka play in the context of climate change and what are the specific challenges that are unique to developing countries?

A: The contribution of the smaller countries to this effort, which is a global effort, can be a very valuable one. The most valuable contribution is an active scientific community that looks at the problem and comes to the table with its unique perspective and expertise. I think for every developing country, the unique challenge is to continue on the development path while being aware of the fact that the development should proceed in a manner in which you will remain competitive 20 years from now.

Q: Sri Lanka depends heavily on thermal and coal-generated power and lacks the financial capabilities to invest in renewable energy sources at the moment. Where do you think the solutions for developing countries lie in terms of investing in infrastructure?

A: It may be wiser in these situations to take a longer term perspective on this. When talking about infrastructural investments you need to question if the infrastructure would make sense in another 20 or 40 years. The best solution for today might not prove to be the best solution across a lifetime; especially during a time when things are changing and technology is advancing at an accelerated pace.

We are looking at alternative ways to harvest energy. Ultimately renewable energy should be accessible to everybody. We should not be fooled during a time when prices for fossil fuels are very low. There is no guarantee that a cheap but very precious resource would be available to us for a very long time. But we should focus the use of those precious resources into processes that do not have a visible alternative at the moment.

Q: Climate change has affected the agriculture sector tremendously over the years and Sri Lanka depends heavily on it. How big a role will climate resilient crops play in the future of agriculture?

A: It’s certainly a research topic being looked into by many centres – to find what we call climate-resilient crops. The question is difficult because every time you look at the crop individually and expose it to higher levels of CO2, higher temperatures, lower levels of precipitation, you find a particular characteristic response. But if that same crop finds itself in a grown eco-system, the responses may be completely different.

We need a full eco-system consideration of the behaviour of crops and also the behaviour of marine eco-systems as it will be a key source of food in the future. Very little is known about that, where we have added effects such as ocean acidification – of which the consequences are not very well-known. I think what IPCC can contribute is a higher awareness of the scientific community to look at these problems. Science will produce more results on these topics.

Q: In Sri Lanka, the apparel sector along with certain sections of the tourism industry have made positive moves towards going green but other sectors seem to lag behind. Do you think governments play an important role in incentivising green exports and products?

A: I think the power of the consumer is much stronger. Eventually it’s the awareness with the consumer that has enabled that attitude and that modified use of resources and materials. Transparent information and the requests for labelling products are important. The consumer needs to be given an instrument by which to make a decision on purchasing goods based on the information provided.

Q (Prof. De Alwis): How successful do you think the UN Climate Change Conference in Paris would be?

A: I usually open most of my statements on this by saying that it is harder to predict the outcome of COP21 in Paris than predicting climate change. I’m an optimist and I do believe that we will have a legally-binding agreement coming out of Paris.

I’m optimistic for three reasons. The first reason being that policy makers have never before been this informed about climate change; the risks, the impacts and the solutions. That is thanks to the fifth assessment report of the IPCC and our efforts to engage in structured expert dialogue which was initiated by the convention.

The second point is that we now have, in contrast to six years ago, a bottom up process, country by country, through the INDC (Intended Nationally Determined Contributions) to greenhouse gas emissions, a call for every country to make a declaration on what they are able to contribute and why their contribution is ambitious. That has changed the dynamics of the discussion and has unlocked a long stalemate where progress was slow.

The last point is the businesses which have also made declarations on this and are in the course of finding solutions. Globally, companies have begun to talk about climate change and have agreed that it is a threat to their business model; they have talked about a global carbon price which is in itself an unimaginable shift from six years ago. These observations make me optimistic.

Q (Prof. De Alwis): Do you think that sticking to technical assessments and steering clear of being policy-prescriptive is going to help the task? It is the policy makers who really make the decisions.

A: I’m aware of that but I also believe that the IPCC is not the only source of information that the policy makers absorb. NGOs, advocacy organisations, think tanks are there as well. I am of the firm conviction that IPCC cannot and must not fall into advocacy of any type. What we can and must do is to communicate clearly, providing information to the stakeholders and the policy makers. From that very evident communication, the consequences of our choices today can be clearly spelled out. I’m convinced that the only source of scientific information comes from IPCC and therefore we must preserve that function. Otherwise the credibility and authority of the scientific voice in this music of information will be contaminated and will not be as powerful as it can be.

Pix by Daminda Harsha Perera