Thursday Mar 12, 2026

Thursday Mar 12, 2026

Saturday, 28 November 2015 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

A Muslim man prays after breaking fast at a mosque in Colombo on 12 July 2013 – Pic by Ishara S. Kodikara/AFP/Getty Images

A Muslim man prays after breaking fast at a mosque in Colombo on 12 July 2013 – Pic by Ishara S. Kodikara/AFP/Getty Images

By Bisthan Batcha

Over the past 1,000 years, as the members of the Muslim community of this island began to take root and become an intrinsic part of its political, social and economic fabric, there were certain specific attributes that came to be associated strongly with this community by the majority community. Some attributes were seen as the ‘strengths’ of the community, while others were perceived as their ‘weaknesses’. Very few traits, if any, were considered as being ‘threats’ by the majority community.

The ‘brand image’ projected by Sri Lankan Muslims would have been shaped and defined by the valence and salience (in a psychological sense) of the attributes associated with the community as perceived by the majority community. However, brand image is not a constant entity. It varies with time and with changing outlooks and expectations. It undergoes revision not only because of changes in the lifestyles of the Muslim community, but more importantly because of changes in the perceptions of the majority community.

It is a matter of fact that over the past three to four decades, the level of piety among Muslims has deepened. It is not intended in this post to examine the causes for this phenomenon. However, an unanticipated consequence of this heightened religiosity is that the perceived ‘strengths’ of the Muslim community have declined, the perceived ‘weaknesses’ of the community have increased and most critically, there has been a quantitative and qualitative amplification of the ‘threats’ as perceived by the majority community.

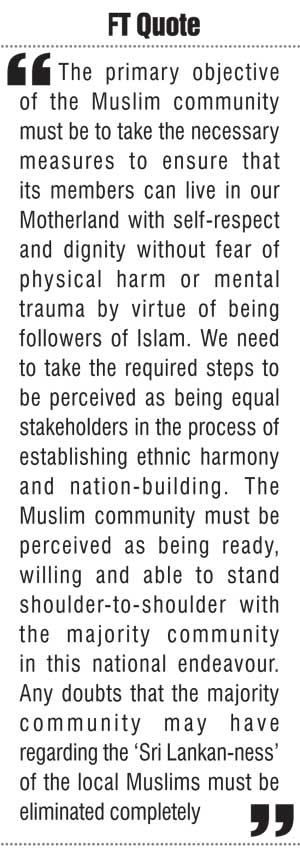

The primary objective of the Muslim community must be to take the necessary measures to ensure that its members can live in our Motherland with self-respect and dignity without fear of physical harm or mental trauma by virtue of being followers of Islam. We need to take the required steps to be perceived as being equal stakeholders in the process of establishing ethnic harmony and nation-building. The Muslim community must be perceived as being ready, willing and able to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the majority community in this national endeavour. Any doubts that the majority community may have regarding the ‘Sri Lankan-ness’ of the local Muslims must be eliminated completely.

This short article will discuss the need for a course of action for an aspect which has to date not received the attention of the Muslim community.

Is the term ‘Sri Lankan Muslims’ a brand?

For purposes of this paper, if we put aside the formal definitions of the term ‘brand’ as proposed by Professor Phillip Kotler et al which may cause some confusion in the minds of readers, and focus on a much simpler definition such as “Any brand is a set of perceptions and images that represent a company, product or service”, then replacing the terms ‘company, product or service’ with the term ‘community’ will justify considering the term ‘Sri Lankan Muslim’ as a brand.

The primary target group for this proposed exercise in social marketing would consist of the members of the majority community in Sri Lanka. It should be emphasised that “Social marketing seeks to develop and integrate marketing concepts with other approaches to influence behaviours that benefit individuals and communities for the greater social good. Social marketing practice is guided by ethical principles. It seeks to integrate research, best practice, theory, audience and partnership insight, to inform the delivery of competition sensitive and segmented social change programmes that are effective, efficient, equitable and sustainable.”

Why is brand image an issue?

The highly-reputed international marketing guru, Dr. Phillip Kotler, has this to say about the concept of ‘image’. “We use the term ‘image’ to represent the sum of beliefs, attitudes and impressions that a person or group has of an object. The object might be a company, product, brand, place or person. The impressions may be true or false, real or imagined, right or wrong, images shape and guide behaviour. Companies need to identify their image strengths and weaknesses and take action to improve their images.”

Furthermore, the Chartered Institute of Marketing (UK) explains the concept of brand image as follows: “People don’t react to reality but to what they perceive as reality. So the set of values people associate with any particular brand is based on both direct and indirect experience of it. This makes it unlikely that two people will have the same image of a brand, although the image may have common features. Understanding this forces managers to analyse consumers’ perceptions and take action to encourage favourable perceptions – and to do so either more or less extensively, depending on customers’ levels of involvement.”

The image of a brand is given a particular form and shape by the positive and negative attributes associated with it by target consumers. It is extremely important therefore to bear in mind that the image of a brand is not the desired picture that the owners of the brand would like to, or strive to, project. The image of a brand refers to the picture that is conjured up in the minds of its target consumers whenever he thinks of the brand name.

What about the brand image of the Muslim community?

As stated previously, the past 30-40 years have witnessed qualitative changes in the religious behaviour and lifestyles of the members of the SL Muslim community. Social and religious walls have been built and are continuing to be built and strengthened between the Muslims and the other communities. Muslim political parties were formed ostensibly to ‘look after the needs of the Muslims’. Islamic theologians assumed responsibility for issues which were perceived to be outside their mandate such as issuing Halal certificates and joining the GOSL delegation to the UNHRC Sessions in Geneva. This created a sense of uneasiness and apprehension among members of the majority community, amplifying the ‘Us vs. Them’ sentiment.

This gradually heightening sense of apprehension expanded in width and depth among the majority community over the last three decades. However, it found no outlet for expression since the whole country was engulfed by a far more vicious and widespread danger due to Tamil Tiger terrorism during this period. With all communities facing a common enemy, there was no opportunity for the surfacing of inter-community differences – at least not on a major scale. But there were signs that such concerns existed. It will be recalled for instance that protests were raised when some Muslims chose to extend their support to the Pakistan Cricket Team when they played against our National Team in Sri Lanka. So the ‘dots’ did emerge, but no one appears to have felt the need to join-the-dots at that time.

Then in May 2009, after Tamil Tiger terrorism was militarily eradicated, the attention of the populace turned towards re-building their lives and the nation. Under these changed conditions, the pinpricks of apprehension and concern experienced by the majority community regarding the Muslims became more sharp and fearful. The target group was willing and ready to listen to the correct message. The conveyors of the message came in the form of the anti-Muslim Groups.

The content of the message resonated with the majority community although many were not happy with the methods of delivery. While criticising the actions of the anti-Muslim groups, many members of the majority community would end their statements by saying “Namuth kiyana eke aththakuth thiyanawa ne?” (Translation: “But there is some truth in what they are saying, no?”) Simply put, such groups were at the correct place at the correct time.

If the attributes currently associated with the Sri Lankan Muslims by the members of the majority community are discerned largely as being ‘negative’ and ‘threatening’, then brand image is definitely an issue and has to be addressed urgently.

Identification of image attributes

The process of identifying and classifying attributes associated with Muslims into perceived strengths, perceived weaknesses and perceived threats can be done in two stages.

Firstly, by conducting content analyses of relevant posts and articles in stridently anti-Muslim websites and blogs. This should reveal the nature of the negative attributes.

Secondly, by conducting informal depth interviews with selected members of the majority community. This would not only enable the elicitation of the more favourable attributes associated with Muslims, but more importantly will reveal the extent and intensity of each negative attribute and the reasons for such sentiments.

This exercise would be the first of two occasions which will cause much consternation, dismay and antagonism among the Muslim community as they are compelled to acknowledge their perceived weaknesses and the threats that they seem to pose to the majority community. Not to do so however would amount to continuing to live in a state of denial. This is a time for objective analysis and independent reasoning. A time to maintain one’s mental composure. A time to demonstrate what it truly means to be a minority Muslim.

Strategy for change

The Muslim community must adopt an ‘empathy-driven’ approach when planning and developing strategies for change. This is easier said than done since most Sri Lankans (including Muslims) suffer from an Empathy Deficit Syndrome (EDS), especially when it involves such emotional subjects as ethnicity and religion.

There is no question of Muslims having to ‘give-up’ any of their Islamic beliefs or practices for this purpose. That would be preposterous. It would only be a case of a group of selected Muslim scholars discussing the merits and demerits of each such change based on the Islamic principles of Shura (consultation) and Ijma (consensus) as recommended by the Holy Prophet (sal).

Why should it be ‘empathy-driven’ some may well ask. The answer is quite simple. Unless the Muslim community is ready, willing and able to look at themselves through the eyes of the majority community, they will not be able to identify the attributes that are perceived as being ‘negative’ and ‘threatening’. In developing solutions to such unfavourable attributes, the modus operandi of the Muslim community should be to introduce measures that would effectively neutralise or diminish the effects of such perceived negative attributes.

This is the second of two occasions in this whole exercise which may cause serious differences of opinion among the Muslims. In the case of each perceived negative attribute, what specific steps should the Muslim community take to negate such perceptions? Arriving at consensual answers to such questions will subject the Muslim community to internal stresses never experienced before. Their leaders will have to demonstrate exceptional inter-personal skills when developing and implementing solutions to these issues.

Do we change the brand name?

The general rule when a brand is given an ‘image make-over’, is to re-launch the brand with a new brand-name. If it is a simple change in image, one could merely add the term ‘New’ to the brand (e.g. New Brand X ). However, if it involves major re-adjustments of the image, then a completely new name is essential for the simple reason that the continued usage of the old brand name will only evoke the old image in the consumer’s mind.

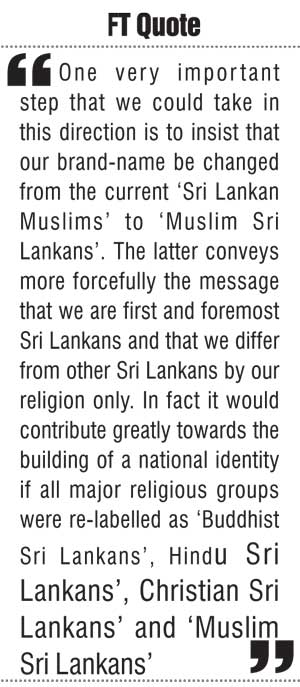

One very important step that we could take in this direction is to insist that our brand-name be changed from the current ‘Sri Lankan Muslims’ to ‘Muslim Sri Lankans’. The latter conveys more forcefully the message that we are first and foremost Sri Lankans and that we differ from other Sri Lankans by our religion only. In fact it would contribute greatly towards the building of a national identity if all major religious groups were re-labelled as ‘Buddhist Sri Lankans’, Hindu Sri Lankans’, Christian Sri Lankans’ and ‘Muslim Sri Lankans’.

The current term ‘Sri Lanka Muslim’ is so weak that even a Muslim academic questioned in a recent article as to whether it refers to ‘Muslims of Sri Lanka’ or ‘Muslims in Sri Lanka’. Just imagine what this term must concoct in the minds of the members of the majority community?

The article titled ‘Strengthening the national identity of Sri Lankan Muslims’ published in the Daily FT of 5 November (http://www.ft.lk/article/492203/Strengthening-the-national-identity-of-Sri-Lankan-Muslims) offers a valid argument for the proposed change of name.