Tuesday Mar 10, 2026

Tuesday Mar 10, 2026

Wednesday, 28 June 2017 00:07 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Ferni Wickremasinghe

By Ferni Wickremasinghe

An ongoing island wide social survey has pointed to a sharp rise in the manufacturing and consumption of illicit alcohol island wide, as many households, particularly in the North, North Central and Eastern Provinces, have begun brewing and selling their own produce.

These products have little or no relation to acceptable standard production practices, and with no regulation over alcohol content or raw material used; they pose a serious threat to health and lifestyles of consumers.

Others have also formed livelihoods around buying and selling arrack to rural tipplers. Sales are available in all forms; from a cup to a flask and even the standard litre bottle, which could fetch a markup of up to Rs. 250.

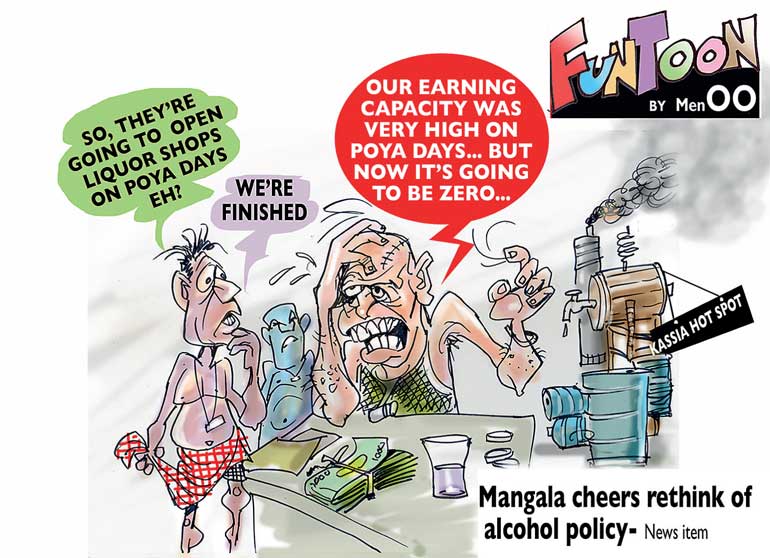

There is a lot of pretence surrounding alcohol consumption all over Sri Lanka, and as witnessed by these findings – yet to be published – the problem is worsening. The consumption of spirits in the form of arrack and kasippu have grown threefold, whilst toddy in the form of a chemical concoction is also emerging as a serious trouble-maker in almost every part – notably the Central and Northern Provinces.

Toddy tavern owners and manufacturers confessed to mixing chemical additives to generate volumes, whilst others opened doors to bottling and selling operations at home. In one village of 600 families, it was estimated that the daily production of illicit toddy was close to 100,000 litres with sales amounting to Rs. 50,000. Money spent on illicit, unregulated harmful products that also breed numerous social ills.

Toddy is no longer a meagre cottage industry. As prices of other licensed products skyrocket, the toddy trade – which enjoys the smallest tax bracket by far – has capitalised to achieve big volumes and trade that are illegal. From the 29 registered bottled toddy manufacturers, the reported volume of production was a mere 5.3 million litres in 2010 and 9.4 million litres in 2015, whereas this study puts the real figure well over 50 million litres annually.

The growth of arrack is also very evident in every part. As evidenced by official records, within the space of just two years Sri Lankan tipplers are consuming 20 million more litres of arrack annually.

Two years ago, Sri Lankans consumed 3.73 million bottles of the 180 millilitre ‘flask’ in a month, and come 2016 the figure tops a baffling nine million. Several young men who staggered over in the middle of the day to lend their views to the survey, proudly stated how they must chug down at least three flasks of arrack a day.

In one village situated in the North Central Province, the nearest registered wine shop was a yawning 33 kilometres away. However, the village centre was littered with broken and discarded bottles of arrack, kasippu and toddy, a result of the efficient delivery network prevalent in the areas. The Police turns a blind eye as they too depend on the same service. In the estate sector, this takes place more openly in three-wheelers and motorbikes, whilst others choose to be more discreet due to social pressures which are limited to the surface.

As witnessed during our engagements island wide, the illicit alcohol trade has grown in an irrepressible manner. The volumes consumed are confounding, and some even put on a legal face selling their produce in labelled containers. They carry the backing and even ownership of powerful politicians and are above every facet of the law. At just Rs. 600 a bottle in some cases, kasippu is definitely a cheaper and potent alternative.

Disproportionate taxation leads to illicit abuse as tipplers seek better kick per buck, depriving the government of over Rs. 50 billion in revenue annually as per estimates. Ill-planned policy will drive consumers underground, depriving Government of revenue, law and order and public health. Every illicit distillery employs unsafe methods of production posing grave risks to the health of consumers and the toddy trade serves as a prime example, with producers using Ceylon Paste in the fermentation process in place of traditional coconut sap.

Our governments have chosen to be reckless with the country’s alcohol policy, whilst the health, social and economic benefits of adopting a safe alcohol policy and culture are well documented globally.

We must learn to be prudent. Prohibition is not the solution, and lawmakers must instead create conducive environments to minimise harm on the user and those around. For a state in want of urgent revenue, they are letting it slip.

We need to start moving our public towards a safer alcohol culture, and that begins with proportionate taxation, distribution, a broader tax net and urgent action to curb the spread of illicit.

(The author is a researcher and analyst engaged in ethnographical and longitudinal research into social and economic behaviour in Sri Lanka and South Asia.)