Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Saturday, 4 July 2015 00:22 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Bisthan Batcha

At a presidential election, the candidate who obtains at least 50% + 1 of the total number of valid votes wins the race. By the time the dust settled on the process that began on 8 January, the post of executive president of Sri Lanka had eluded Mahinda Rajapaksa by a mere 293,637 votes – a little less than 2.5% of the total valid votes.

Over the past three months, many analysts have brought to bear their expertise in such diverse fields as politics, sociology, economics, statistics, psychology, psephology and even astrology to offer an understanding of what happened on that fateful day.

The 5,768,090 votes that Mahinda Rajapaksa garnered translates into winning 90 of the 160 electorates under a first-pass-the-post system or 104 of the 225 seats under the current PR system – a clear winner in the popularity stakes in both cases.

Destruction of a basic human need

The anger and disappointment among the members of the MR camp is therefore under the circumstances quite understandable. Unfortunately, in their hurry to identify the primary cause for the debacle of their candidate at the polls, many MR supporters chose to externalise the issue and the finger of blame was firmly pointed at the minorities.

True, the votes of the minorities had played a decisive role at the election, but if these MR-supporters had examined the situation dispassionately, they would have realised that this was only the effect of a specific phenomenon and not its cause. The real cause of the phenomenon in the case of the Sri Lankan Muslim community was the total destruction of a basic human need – the need for physical safety.

Abraham Maslow identified a Hierarchy of Needs as being the driving or motivating factors of human behaviour. At the most basic level are the primary needs for food, shelter and sex. At the next level are the safety needs – consisting of the need for physical safety, financial safety, etc.

By failing to demonstrate by word and deed the leadership qualities that were essential to allay the growing fears of the Muslim community during the period 2012-2014, Mahinda Rajapaksa alienated himself totally from the Muslim community. Asked by a non-Muslim friend, just prior to the presidential poll, as to what proportion of the Muslims in my opinion would vote for Mahinda Rajapaksa, there was no hesitation on my part when I responded “1%” – which he found pretty hilarious.

But the fact of the matter is that like many Muslims, my response was based on inductive inferences rather than on deductive conclusions. By his inactions as the President of all Sri Lankans, Mahinda Rajapaksa simply destroyed a basic need of the Muslims, period.

The efforts of Mahinda Rajapaksa to win the goodwill of the Muslims thereafter (on 28 October 2014) by offering to devise a method that ensures equal opportunities for all Muslims to undertake the Haj pilgrimage fell flat. Would any Muslim with an iota of intelligence undertake a Haj pilgrimage when the lives and limbs of his family are in acute danger back home? Who is the cretinous mutt who persuaded Mahinda Rajapaksa to make such a stupid offer? This gesture was perceived by the Muslim community as adding insult to injury.

Ethnic composition of votes

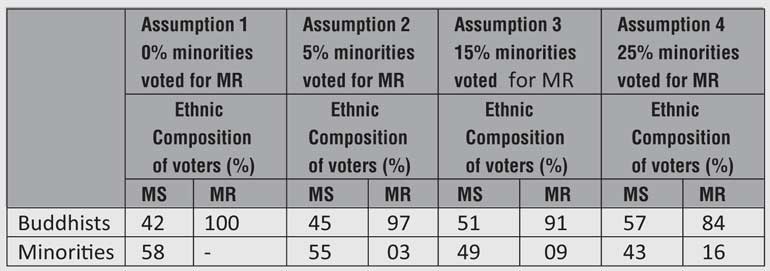

So what was the ethnic composition of the votes received by the two main contenders at the presidential election? The true answer to this question will never be known, but using a minimum number of assumptions (Occam’s Razor), the parameters of an interval estimate may be determined.

A formula could be worked out very easily for the general case where n% of minorities voted for Mahinda Rajapaksa, but I shall refrain from doing so since the less-numerate among the readers may find it daunting. But the calculation in specific cases is extremely simple.

It appears therefore that if no member of the minority communities voted for Mahinda Rajapaksa, then of those who voted for Maithripala Sirisena, a little over 40% are Sinhala Buddhists. If on the other hand we assume that one in seven members of the minority community (15%) voted for Mahinda Rajapaksa, then of those who voted for Maithripala Sirisena, a little over 50% are Sinhala Buddhists. This gives lie to the popular belief that Maithripala Sirisena lacks support among the Sinhala Buddhists. But clearly Mahinda Rajapaksa does lack the support of the minority communities.

As a Sri Lankan Muslim, I cannot comment on or predict the behaviour of non-Muslim minorities at future elections. However, the following important points regarding the Muslim voters have to be taken cognisance of.

SLFP and UPFA

The aversion of Muslim voters towards Mahinda Rajapaksa has created an aversion towards the SLFP and the UPFA. Except for one or two UPFA Parliamentarians, the vast majority remained mum as the Muslim community reeled under the onslaught of the anti-Muslim groups during the period 2012-2014. They were therefore perceived as passively supporting the objectives and actions of such racist groups.

The feelings of the Muslims towards the SLFP/UPFA will manifest itself strongly at the next general election. The JVP is expected to be the main beneficiary of disgruntled previous SLFP/UPFA Muslim supporters.

Muslim political parties

The Muslim political parties are often described by the media as the ‘representatives of the Muslims’. Nothing could be more further from the truth. Following the violence at Aluthgama, the members of the Muslim community independently and almost to a man decided as to who they will not vote for at any future presidential election. The Muslim community did not wait with bated breath for the so-called Muslim political parties to give them leadership in this regard.

Estimates based on the performance of these Muslim political parties at the Provincial Council Elections held in Eastern, Northern and Western Provinces during the recent past reveal that only about 18% of Muslim voters have cast their votes for a Muslim political party. This means that around five out of every six Muslim voters have either cast their votes for a ‘non-Muslim’ party or have not been sufficiently motivated to vote for any individual.

Thus, if such Muslim political parties believe that they represent the Muslim community, they are only flattering and fooling themselves. Their ‘combined’ performance at the last Uva Provincial Council elections in 2014, where they were totally ignored by around seven out of eight Muslim voters should serve as an eye-opener in this regard.

The reason for this is quite simple. The Muslim political parties, severally or collectively, are not perceived as being capable of restoring the Muslim community’s basic need for physical safety – even at a point in time when this need is most intense.

Overarching need of Muslim community

The overarching need of the Muslim community is the immediate restoration of their violated basic need for safety. This felt need encompasses Muslims of all socio-economic groups and resident in all parts of the Island – a Muslim need which is not ‘local’ or ‘regional’ in character, but truly ‘national’.

It would appear to be the case that the Sri Lankan Muslims have realised that it is only a truly national political party (e.g. UNP, SLFP and JVP) that can address this primary problem effectively. If the SLFP has any interest whatsoever in redeeming and retaining the support of Muslim voters at the next general election, it is imperative that the party issues a ‘mea culpa’ statement acknowledging its abject failure as a national party to prevent by word and deed the destruction of this basic need of the Muslim community in Sri Lanka.

The leaders of the SLFP should bear in mind that ‘apologising means that you value your relationships more than your ego’. However, the pragmatic Muslim community is not expecting an apology, which normally results from something that is said or done. But a sincere statement of regret from the SLFP leadership for remaining deaf, dumb and blind to the deliberate and well-planned destruction of the physical security of the Muslims will certainly go a very long way towards mending fences with the Sri Lanka Muslim community.