Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Saturday, 15 October 2016 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

A view of Colombo’s Port from the Harbour Room restaurant, located in a 179-year-old hotel

By Marwaan Macan-Markar, Asia Regional Correspondent

asia.nikkei.com: At the Harbour Room, a shabby restaurant in a British colonial-era hotel in the Sri Lankan capital, diners tuck into a standard Asian buffet and listen to the soporific tones of a pianist. The main draw is the seating near the bay windows, which offer panoramic views of the port of Colombo. These days, the restaurant provides a vantage point for watching the Government’s tricky geopolitical balancing act play out in South Asia’s busiest harbour.

At the heart of the Government’s dilemma is the expansion of the 1,200-meter-long East Container Terminal, half of which is completed. The coalition Government, which came to power after a surprise victory in the January 2015 presidential election, has already closed the tender for this $500 million investment after receiving 20 bids. But the Government is torn between India and China, which are both eyeing the South Asian island’s strategic location on the Indian Ocean.

At this point, China has the stronger pull: China Merchants Port Holdings owns 85% of the Colombo International Container Terminals, the newest facility on the southern stretch of the port, operating since 2013. To balance that, President Maithripala Sirisena’s Government is hoping to secure a stake for an Indian company in the ECT expansion.

“The Government will retain 15% of the stake, like in the other terminals, but for the ECT we would like 20% of the stake to go to a South Asian company – like an Indian company – or one from this region,” Malik Samarawickrama, Minister of Development Strategies and International Trade, told the Nikkei Asian Review. “We need a strategic investor from the region because 70-75% of cargo handled in the Colombo port is transhipment cargo to and from India.”

Wedded to Beijing

The Government is attempting to rebalance the country’s diplomatic interests, and that includes breaking from the pro-China tilt of autocratic former President Mahinda Rajapaksa. Seasoned foreign policy observers see this as timely, given declining US influence and rising Indian, Chinese and Japanese power in the contested waters of the Indian Ocean. “Our interest is to show we offer economic and commercial opportunities for everybody to benefit from,” a veteran Sri Lankan diplomat said.

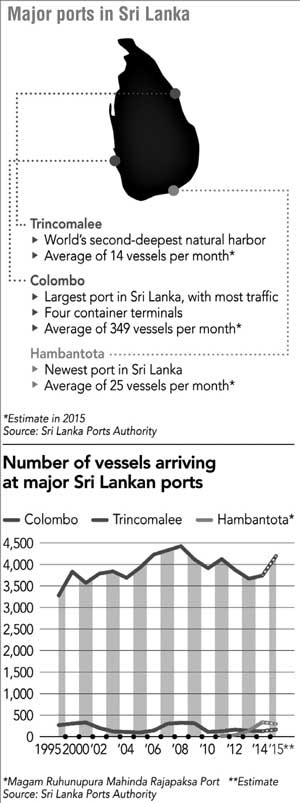

The Government’s vision is to build a “maritime economy” through logistics and transhipment. It aims to make the most of the country’s position on one of the world’s busiest shipping routes, plied annually by 60,000 ships carrying 66% of the world’s oil and 50% of its container cargo. Aside from Colombo, the Government’s plans also include the ports of Hambantota in the south and Trincomalee in the northeast.

Despite the move to draw investment from a wider group of countries, Sri Lanka cannot afford to freeze the Chinese out. Samarawickrama is eyeing Chinese foreign direct investment for Hambantota, a multimillion dollar port built by China. Beijing propped up Rajapaksa’s regime with billions of dollars in loans for infrastructure projects. But the harbour ended up as a loss-maker after the completion of the first of three phases – falling short of the original aim of becoming South Asia’s largest port and a pivotal element in China’s Belt and Road infrastructure initiative.

“We have been talking to the Chinese Government and State-Owned Enterprises to support an integrated development plan, including the port, a huge industrial zone and the international airport, so that companies from China and other places can set up plants to make use of our location,” Samarawickrama said. Discussions have progressed on two refineries, a natural gas power plant, dockyards and a container terminal in an investment blueprint intended to “attract $10 billion to Hambantota over the next two to three years,” he added.

But there is a hitch. Samarawickrama has been the Government’s point man to tempt the Chinese into a debt-for-equity swap for the Hambantota port and airport, built with nearly $500 million in loans from the Export-Import Bank of China. Rajapaksa’s spending spree has left the country with $8 billion in sovereign debt owed to China, much of it at commercial interest rates as high as Libor plus 6%. “We are hoping they [the Chinese] will take at least 70% of the debt in this swap, and we are talking to the Chinese on this basis for Hambantota’s development,” he said, contradicting local reports that China is opposed to renegotiating the debt.

The Government also ran into trouble with a $1.4 billion project to build a modern commercial hub on reclaimed land south of Colombo’s harbour. This Chinese project, initially called Colombo Port City, began during Rajapaksa’s term. It drew protests from environmentalists, worried about damage from erosion along the western coast, and objections from India, after Rajapaksa pledged a slice of freehold land to the Chinese.

Back on track

Sirisena’s coalition Government stopped the project last year and renegotiated the deal, which covers 267 hectares, upsetting the Chinese. But a Chinese dredger returned to the waters off Colombo in early October to resume work, affirming that the project – renamed Colombo International Financial City, with planned hotels, shopping malls and a marina – is back on track.

Development plans in the northeastern Trincomalee port, the world’s second-deepest natural harbour, are less problematic. After being caught in the crossfire during Sri Lanka’s 30-year civil war, and used as a security asset by the Navy, Trincomalee is about to receive a makeover. The Government has given the green light to Singapore’s Surbana Jurong, an urban planning consultancy, to draft a development plan to transform the storied port city.

Samarawickrama is in talks with potential investors from Japan, India and Singapore to tap this corner of the Government’s maritime economy map, balancing China’s dominance in the south. “The Japanese are interested in light industries and automotive components,” he said.

So far, the country’s economic diplomacy has not translated into a rise in foreign direct investment. Last year, Sri Lanka fell short of securing $1 billion in FDI, after crossing that threshold a few years earlier. The country’s poor showings in Global Competitiveness Index rankings are cited as a deterrent to international investors. The country slipped three places to sit at 71 in rankings issued in late September by the World Economic Forum.

Samarawickrama blames the dismal global rankings on an “island mentality” and “inward-looking” domestic business environment. A World Bank study shows that “our economy is as closed as it was in 1970,” he said, referring to the year when a socialist government was elected. “We cannot grow by only catering to our 20 million population; we have to look to the world as our market.”

The Minister does not have to move far to measure shifts in economic currents. From his 25th-floor office, high above the Port of Colombo, he will have a bird’s-eye view of the success or failure of his country’s maritime economy ambitions.