Wednesday Jul 02, 2025

Wednesday Jul 02, 2025

Saturday, 9 April 2016 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

A sign in Sri Lanka’s three languages – Sinhala, Tamil and English – and Chinese on a fence bordering the site of the Colombo Port City (Photo by Marwaan Macan-Markar)

By Marwaan Macan-Markar

http://asia.nikkei.com: A mechanical excavator stands idle on an uneven strip of land reclaimed from the sea near Colombo’s waterfront. Nearby is an empty iron shed beside a mound of rocks. The only sign of life is a few men in hardhats moving about aimlessly, adding to the impression of an abandoned construction site next to the Sri Lankan capital’s busy harbour.

The site, on the western edge of the Fort, Colombo’s historic commercial hub, is an unlikely emblem of the uneasy diplomatic and economic relationship between Sri Lanka’s coalition government, in power since a presidential election in January 2015, and China, the country’s largest foreign lender and investor.

The uneasiness stems from Colombo’s decision in March 2015 to put the brakes on plans for a Chinese-funded project known as Colombo Port City, which would include hotels, shopping centres, offices, marinas and even a golf course on 233 hectares of  reclaimed land. The government said it was halting the development because of environmental concerns and irregular approvals pushed through by the previous government.

reclaimed land. The government said it was halting the development because of environmental concerns and irregular approvals pushed through by the previous government.

A year later, Colombo is singing a different tune, announcing recently that it has eased restraints on the project, expected to cost $1.4 billion. The about-face on China’s largest investment in Sri Lanka came as Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe, once an outspoken critic of the scheme, began a three-day official visit to China on 6 April.

Sri Lankan officials who visited Beijing ahead of the prime minister’s trip say the Chinese government and the consortium backing the project have warmed to Colombo’s concerns. International Trade Minister Malik Samarawickrema, who led the advance party, had zeroed in on the public pressure raised by environmentalists during talks with his counterparts.

“Sri Lanka has very high environmental standards ... [and] the government wanted the right level of transparency for the project,” said Duminda Ariyasinghe, Director General of Sri Lanka’s Board of Investment, who accompanied Samarawickrema. “Being extra careful is not a negative,” he told the Nikkei Asian Review.

The same benchmarks will be used to attract further Chinese foreign investment to Sri Lanka. Wickremesinghe’s list includes a pitch for Chinese infrastructure investment in an integrated development plan in Hambantota, a southern coastal town, where a Chinese-built harbour and airport would be included in an export processing zone for manufacturing and services.

However, a highly-placed insider in Sri Lanka’s infrastructure industry said there could be further problems with the Port City project. “Technically, the [Sri Lankan] cabinet has given the project the green light to proceed. However, there could be some other unresolved issues,” he said, speaking on condition of anonymity.

Foremost is the touchy issue of a 20-hectare sliver of land on the artificial island, which state-controlled China Communications Construction, the parent company of the Port City’s builder, CHEC Port City Colombo, was to receive freehold. It is understood that the Chinese have not completely embraced amendments to the Port City agreement made by the Sri Lankans in March, under  which the land would be leased to CCC for 99 years – the arrangement that will apply to the rest of the reclaimed land.

which the land would be leased to CCC for 99 years – the arrangement that will apply to the rest of the reclaimed land.

Sri Lanka’s pursuit of Chinese investment comes against a backdrop of slowing economic growth, a large fiscal deficit and unsustainable interest payments on foreign debt piled up by the previous government. The government is seeking a $1.5 billion loan from the International Monetary Fund to prevent a balance of payments crisis, having failed to meet the goals of its Five-Year National Export Strategic Plan, launched with much fanfare in 2010, under which annual exports were supposed to reach $15 billion by 2015. Last year, Sri Lanka shipped $10 billion worth of products, the annual average for the previous five years.

Tilt to Beijing

The strains in Sri Lanka’s ties with China contrast sharply with relations before the presidential poll, when former President Mahinda Rajapaksa ruled with an authoritarian grip. His decade in power, which saw Sri Lankan troops defeat separatist Tamil Tiger rebels in a long civil war, was marked by a tilt toward Beijing for defence, diplomatic and economic support, including more than $5 billion in loans at commercial rates of interest for infrastructure projects such as Hambantota’s new port and airport.

But China’s growing influence on the island unnerved India, Sri Lanka’s northern neighbour. The last straw for Delhi was the presence of Chinese submarines in Colombo harbour in 2014.

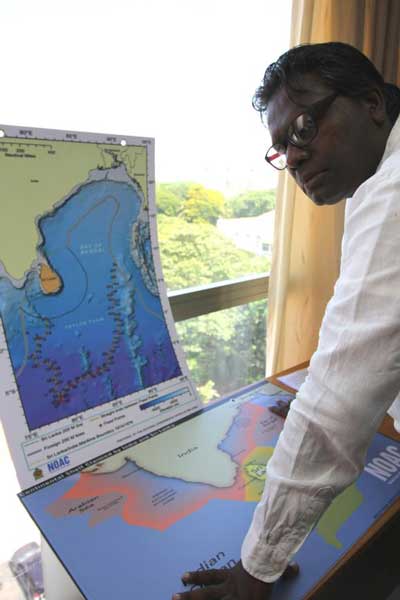

India wants Sri Lanka to acknowledge that it is a “citadel of Indian security,” said Chris Dharmakirti, Chairman of the National Ocean Affairs Committee, a government agency. “We have to acknowledge that apprehension, and not allow Sri Lanka to be seen as a base to destabilise India. The submarines were a problem, because India was not notified.”

In light of India’s concerns President Maithripala Sirisena, Rajapaksa’s successor, has stressed a rebalancing of the island’s international relations, flagging neutrality. That has earned rewards, such as a reduction in international criticism of human rights violations, which peaked during the Rajapaksa years.

The shift has been aided by traditional western allies such as the United States. Admiral Harry B. Harris, head of the U.S. Pacific Command, told the Senate Armed Services Committee in early February that Sirisena was “serious about addressing Sri Lanka’s human rights issues.” He added, “We have an opportunity to expand U.S. interests with Sri Lanka.”

Washington’s changing view of Sri Lanka comes in the wake of growing awareness within the island’s own foreign policy circles of the country’s rising strategic value in the Indian Ocean. Seminars on maritime affairs regularly focus on the sea lanes between Sri Lanka and the Maldives – a chokepoint for busy ocean traffic where more than 60,000 ships ply annually, ferrying 66% of the world’s oil and 50% of container shipments.

Some analysts say the views of strategists at Beijing’s National Defence University that the “Indian Ocean Region cannot be referred to as India’s backyard” imply that China wants more than a toehold in Sri Lanka.

Imtiaz Ahmed, Executive Director of the Regional Center for Strategic Studies, an independent think tank in Colombo, said the Sirisena administration’s objective was to strike a balance between India, China and the US by keeping economic development separate from security issues. The government’s decision to woo Chinese investments “means they have already briefed Delhi and India is comfortable,” he said. “I don’t see a conflict between India and China looming over the Port City project.”

Nevertheless, Wickremesinghe may have his work cut out to convince his interlocutors in Beijing that his coalition is fully committed to a strong and growing business relationship with China. The test for the veteran politician is whether he can lay their anxieties to rest without provoking criticism at home of excessive kowtowing in Beijing.

Discover Kapruka, the leading online shopping platform in Sri Lanka, where you can conveniently send Gifts and Flowers to your loved ones for any event including Valentine ’s Day. Explore a wide range of popular Shopping Categories on Kapruka, including Toys, Groceries, Electronics, Birthday Cakes, Fruits, Chocolates, Flower Bouquets, Clothing, Watches, Lingerie, Gift Sets and Jewellery. Also if you’re interested in selling with Kapruka, Partner Central by Kapruka is the best solution to start with. Moreover, through Kapruka Global Shop, you can also enjoy the convenience of purchasing products from renowned platforms like Amazon and eBay and have them delivered to Sri Lanka.

Discover Kapruka, the leading online shopping platform in Sri Lanka, where you can conveniently send Gifts and Flowers to your loved ones for any event including Valentine ’s Day. Explore a wide range of popular Shopping Categories on Kapruka, including Toys, Groceries, Electronics, Birthday Cakes, Fruits, Chocolates, Flower Bouquets, Clothing, Watches, Lingerie, Gift Sets and Jewellery. Also if you’re interested in selling with Kapruka, Partner Central by Kapruka is the best solution to start with. Moreover, through Kapruka Global Shop, you can also enjoy the convenience of purchasing products from renowned platforms like Amazon and eBay and have them delivered to Sri Lanka.