Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Friday, 3 July 2015 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Critics say that

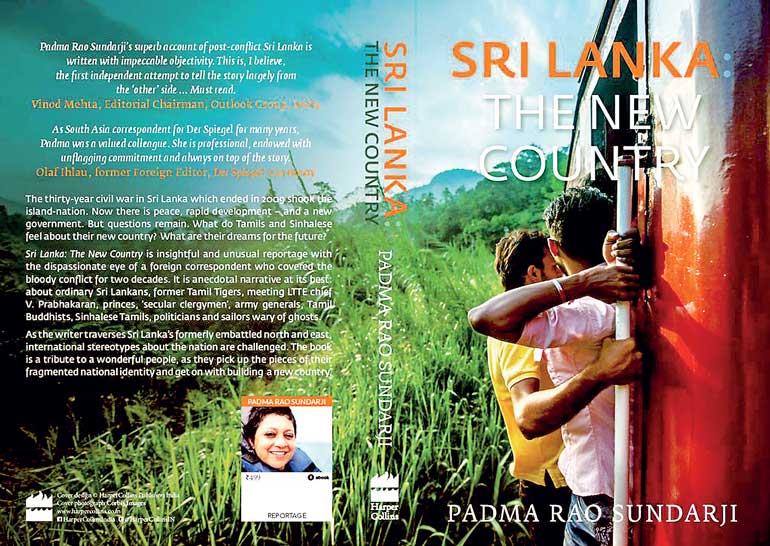

‘Sri Lanka: The New Country’ is a refreshing change from the many tomes penned by international war analysts, the accounts of corrupt journalism and few notable biographies. Its author, Padma Rao Sundarji, presents an insightful study on post-war Sri Lanka, drawing from her experience covering the Sri Lankan civil war and various other issues across South Asian for 14 years until 2012 as a freelance correspondent for the Hindustan Times and several other European media outlets. She was also the South Asia Bureau Chief of Der Spiegel. With just days left until the book’s launch in Colombo, the Daily FT caught up with Sundarjion for a conversation about her work. The following

are excerpts.

By Sarah Hannan

Q: Can you tell me about your first assignment in Sri Lanka and the rest of your time in Sri Lanka?

A: I was assigned the Sri Lanka story several times in the late eighties (when Prabhakaran was a ‘state guest’ of the Government of India and lived in a suite in the Ashoka Hotel in Delhi) and again in the nineties. But my real, most intensive and longest engagement with the Sri Lankan civil war and the country began in 1998 when I took over as South Asia Bureau Chief of German magazine Der Spiegel.

After the ceasefire of 2002 and Prabhakaran’s press conference in the Vanni - a trip for which I spent about two weeks in Sri Lanka - my fascination with the country really took off. I was travelling to Sri Lanka almost every two months thereafter for 14 long years. Even after I quit the magazine in 2012 and right up to the present, I think I am in Sri Lanka on average for about three to five times a year as a freelance correspondent for various other Indian and international publications.

Q: What inspired you to turn your experiences into a book and how long did it take for you to compile it?

A: I must correct the erroneous impression that my book ‘Sri Lanka: The New Country’ is a recycling of those old reports; far from it. It is entirely about post-war Sri Lanka and I researched it entirely between 2012 and right up to the January 2015 presidential elections, which are included towards the end of the book.

In fact, I recalled my manuscript after it had already been sent in and travelled for the elections, interviewed both President Maithripala Sirisena and Prime Minister Ranil Wickremasinghe, added a chapter and then returned the manuscript to the publisher.

All in all, it must have taken me about three years to research and compile. But and this is important: foreign writers who have not experienced the long and bloody civil war first-hand - as I did, not by sitting on the Galle Face terrace sipping sundowners and hammering their laptops but by actually travelling to the warzone whenever the army permitted it - cannot understand or appreciate post-war Sri Lanka in its entirety. It is for this reason that the book occasionally goes back to those dark years of war. One cannot contrast or appreciate Sri Lanka as a new country unless one knew the terrible days of the old country.

Q: Considering Sri Lanka’s conflict-plagued past and the humanitarian issues that currently exist in the North and East, do you believe Sri Lanka has at least remotely achieved a degree of peace?

A: Remotely? If you are talking about peace, my answer is absolutely! But I think your question is really getting at a political solution to the satisfaction of Sri Lankan Tamils in the North and East. To that, my answer would be not yet. But I would request all western-educated, liberal-minded journalists in Sri Lanka to please not look at their own country through the prism of the West or be influenced by western reportage.

There is no one-size-fits-all timetable or framework for democracy and political solutions, nor is there an instant noodle-type remedy to solve a problem of what is essentially an ancient and very complex society. Please be proud of what your country has achieved. Please look forward, not back. I would implore all young Sri Lankans reading this, regardless of their demographics, to cast aside the rubbish that mostly appears in the international media and take a fresh and proud look at their own country through their own cultural prism.

I request them to find home-grown solutions, not seek to force-fit one tailored in the West. There are plenty, just go down the long road of various solutions eked out at various times by your own politicians and statesmen. They failed in the past for various reasons but all Sri Lankans have lived and learned through one of the longest and bloodiest conflicts in the history of mankind.

Q: As a journalist were you able to easily reach displaced communities while on assignment? What sort of roadblocks did you face and how did you handle these situations?

A: During my nearing 20 years covering Sri Lanka, I have never once been obstructed, censored, harassed or denied access to whatever and whomsoever I wanted to meet by the Sri Lankan Foreign Ministry, the Armed Forces or even the Tigers.

I can say this in all honesty. But then if there are people who did face such problems they must ask themselves why. Many arrived here on tourist visas and proceeded to write damning reports about Sri Lanka. That is an outright visa violation, one which Sri Lankans or Indians would be deported from western countries for. There is something known as a media visa for Sri Lanka. It may take a day longer to get but it is available. Many others came here with agendas, either those of individuals, media outlets or NGOs and wrote their reports based not upon what they saw or experienced but exclusively for those agendas. Perhaps it is because I never did that and got frequently slammed by both Sinhalese as well as Tamil chauvinists for my reportage in Der Spiegel, something which I am thankful for, that I was never denied a press visa.

I even remember the Sri Lankan High Commission in Delhi opening its doors on a Sunday, hurrying out in tracksuits and stamping my passport as I made my way to the airport as soon as the first wave of the tsunami hit the shores of Sri Lanka. If I sound smug, I can’t help it. This is the truth whether the western-educated liberal elite in your country or mine want to hear it or not.

The only thing I kick myself for and intend to change in the coming year? That I have never been in your beautiful country with a tourist visa. I have yet to see Anuradhapura, Sigiriya and bow my head to the magnificent Buddha in repose in Polonnaruwa. To me, all these places were always transit stops on my way up to the North or East.

Q: There are quite a few books published during and after the civil war in Sri Lanka. What makes ‘Sri Lanka: New Country’ stand out from those publications?

A: Many of the more recent books on post-war Sri Lanka by other foreigners like me are undoubtedly by good writers. But there are some essential differences, age and experience for one.

I have covered Sri Lanka as a war and current affairs correspondent for nearly 20 years now. Being in my fifties, I am older and more experienced. Naturally, this lends my approach and vision a maturity that they cannot possibly have.

Consequently, most of the other writers have played safe by relying on whatever colours international opinion of your country such as views held in the western media, by international human rights groups, etc. I must stress that it is impossible to understand post-war Sri Lanka without having experienced the horrors and the intensity of war-time Sri Lanka as I did. Their rhetoric looks back, again and again. Mine is focused entirely on looking forward. I don’t believe in analysing and hacking to death the past, over and over again. It is counterproductive. What Sri Lanka needs is respect from the outside world and what Sri Lankans need is acknowledgement of and regard for what is one of the most literate societies in South Asia, one which is perfectly endowed with the capability of solving its own problems such as seeking a lasting political solution for the North and East.

It is a combination of all these factors that is contained in the pages of ‘Sri Lanka: The New Country’. Indeed it is this approach that makes it uniquely different.