Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday, 17 August 2015 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Bilesha Weeraratne

With the general election just days away, all contesting parties have pledged new job opportunities; the United National Party’s (UNP) election manifesto pledges one million new jobs in five years, the United People’s Freedom Alliance (UPFA) tops it off with 1.5 million jobs by 2020, while the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) promises 60,000 jobs per year through Board of Investment (BOI) projects. But does Sri Lanka need that many jobs?

Current status

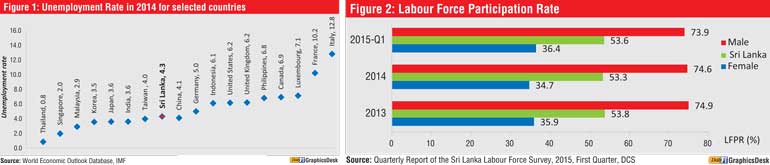

The country’s unemployment rate was 4.3% in 2014, while during the first quarter of 2015 it reached 4.7%. This level of unemployment, however, does not indicate that Sri Lanka’s labour market is in a terrible state. In fact, it is worth reminding that full employment is not 0% unemployment, and that full employment is an acceptable figure above 0% that is consistent with stable inflation.

Figure 1 depicts Sri Lanka’s unemployment rate in 2014 compared to several selected countries. For instance, in the UK and USA unemployment rates in 2014 were 6.2 %, while in Japan it was 3.6%. In China and India it was 4.1% and 3.6% respectively.

Sri Lanka does not have a dire need for the creation of that many new jobs. On the contrary there is a growing shortage of skilled and unskilled labour in many sectors i.e. apparel, plantations and construction. Hence, this existing level of unemployment in Sri Lanka is more nuanced than the inadequacy of jobs. Hidden within the 4.7% unemployment rate are the specific issues such as huge disparities in unemployment rates across age groups, the noticeable gender gap in Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR), and underemployment.

Youth unemployment and new entrants

Amidst somewhat complacent 4.7% overall unemployment, those in the age group of 15-24 years have a high unemployment rate of 21.7% - nearly five times the national average (see Table 1). Similarly, those aged 25-29 years have an unemployment rate of 8.7% – nearly twice the national average. The high-level of youth unemployment in Sri Lanka is mainly due to new entrants to the labour market.

New entrants (also called first time job seekers) often endure a longer stint of unemployment looking for the ideal job that meets their aspirations. As noted by the International Labour Organisation (ILO), jobs available in Sri Lanka are either unattractive to young persons due to; the precarious nature of employment, perceptions of youth about the occupation, stigma attached to the particular occupation, or the sector, or because labour market opportunities simply do not meet their aspirations.

A media article points out that youth unemployment “is more marked amongst ‘educated’ young persons who have often secured a qualification without relevant work experience. It is perhaps better articulated as a misunderstanding of the demands of the world of work. Hence once qualified they raise the bar of their aspirational goals, soon to be disappointed and disillusioned.” As seen in the left most panel in Table 1, unemployment is highest among the more educated. Hence, the mere availability of more jobs will have limited impact on solving youth unemployment issue in Sri Lanka.

Low female labour force participation

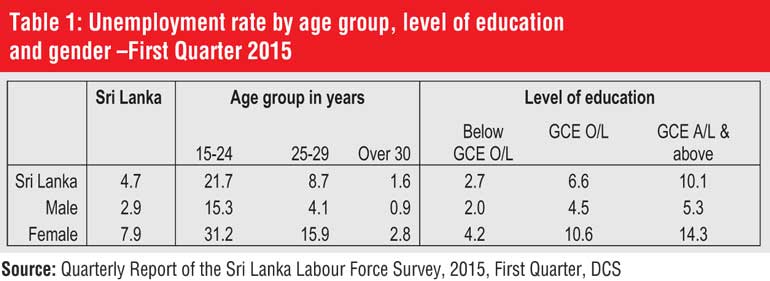

Along with youth unemployment, low female Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR) is another specific issue in the country’s labour market. LFPR is the percentage of people who are working/ looking for work (defined economically active), to the total working age population.

Despite female LFPR being a driver of growth and development, in Sri Lanka there is a large gender gap in LFPR. In the first quarter of 2015, the female LFPR rate was 36.4%, which is half the male rate of 73.9%. This low level of LFPR among women is an indication of the relatively low availability of employment opportunities in Sri Lanka that are suitable for women.

As such, despite sounding attractive in the run up to an election, these pledges to create millions of new employment opportunities will have a limited impact on addressing specific issues of youth unemployment and low LFPR. Moreover, such job creation has the potential to contribute to the growing issue of underemployment - working fewer hours than one desires to work or being employed in a job that does not fully utilise the skills/training.

Unfortunately, Sri Lanka only measures the first form of underemployment – in terms of hours employed, and latest available estimates (2013) indicates that such underemployment was 3.5%. Nonetheless, though not estimated, the other form of underemployment is rampant in the public sector, i.e., the recent graduates’ employment scheme to the position of District Service Officers and most previous graduate employment schemes fail to utilise these graduates’ full potential.

In conclusion, Sri Lanka does not need that many new jobs. Instead, the focus should be on generating adequate good jobs – with greater added value, better wages and working conditions, that are targeted to address youth unemployment and low female labour force participation.

[Dr. Bilesha Weeraratne is a Research Fellow at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS). To view this article online and to share comments, visit the IPS Blog ‘Talking Economics’ – www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics.]