Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Friday, 19 August 2016 00:02 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Chantal Sirisena

The tourism sector is one of Sri Lanka’s success stories of the post-war economy. The industry represents Sri Lanka’s third largest foreign exchange earner, accumulating $2.8bin earnings last year. In 2015, the sector recorded close to 1.8mtourist arrivals, equating to a compoundannual growth rate of22% over the past five years.

These results have been achieved through targeted investments in infrastructure development, tourist attractions, and strategic promotional campaigns. However, the industry holds further potential; critical to unlocking this is the issue of foreign land ownership.

Unmet demand

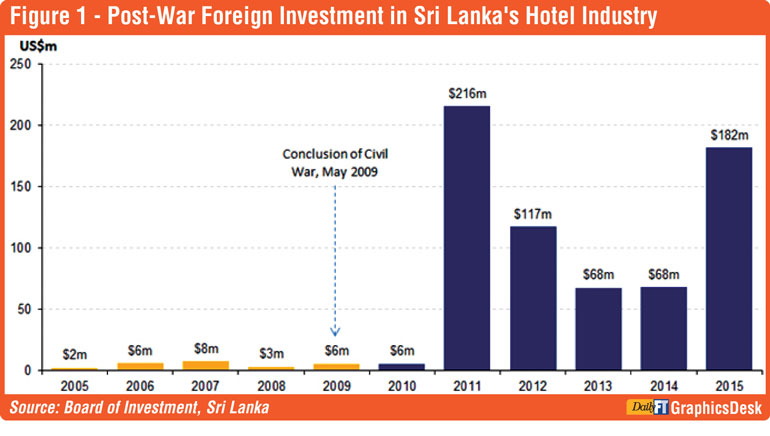

Buoyed by the evident capacity for growth, foreign investment has begun to capitalise on the opportunity that tourism presents. Foreign investment into the hotel industry has experienced significant inbound growth since the end of the war (see Figure 1).

Projects underway indicate a pipeline of 8,000 new rooms in the country (3,500 within the next five years). This sizeable expansion has led to some forecasts of an oversupply of hotel rooms. However, the potential for growth in demand is also understated.

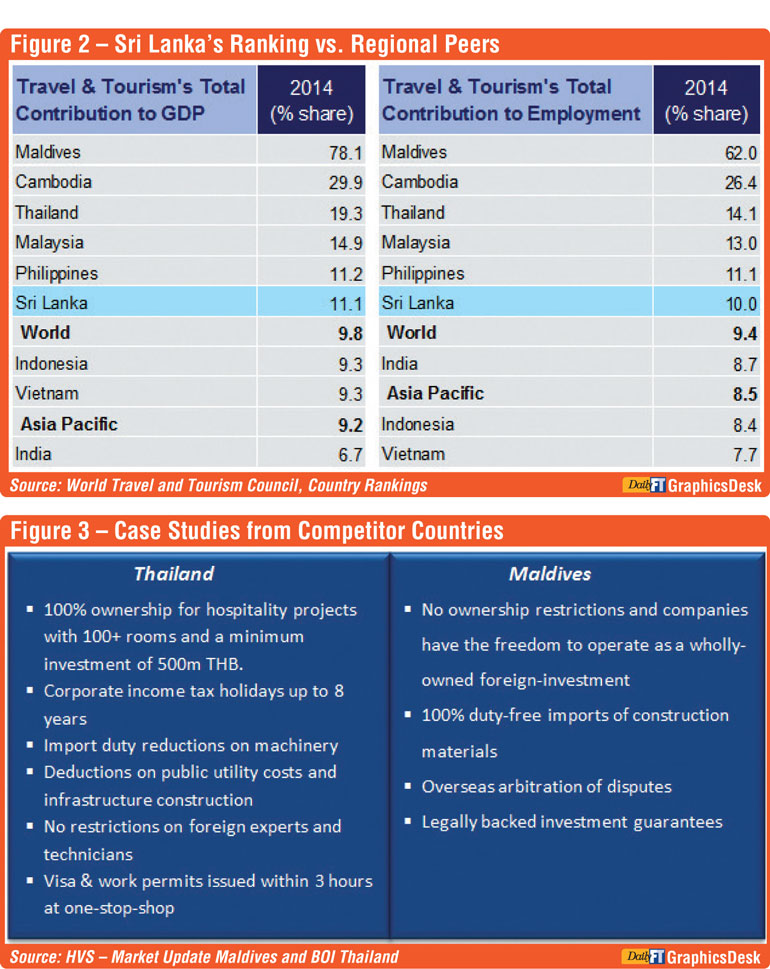

Despite encouraging growth statistics, Sri Lanka is yet to find its niche in the fast changing global tourist landscape. According to the World Travel and Tourism Council (see Figure 2), tourism’s total contribution to both GDP and employment of Sri Lanka is comparatively lower than regional competitors such as Maldives, Cambodia, Thailand and Malaysia.

Sri Lanka can, for example, do more to take advantage of opportunities in the MICE (Meeting, Incentive, Conference and Exhibitions) space given its heavy-weighting to high-end and Colombo-based hotels. Shopping and nightlife also hold potential for tourism with several new shopping malls under development. Harnessing these prospects is something that foreign competition and ideas can catalyse.

A closer examination of supply also shows that theproliferation of new projects is concentrated in the luxury space with 60% of proposed new supply falling into the upscalecategory. Outside of the high-end segment, supply is limited. Mid-scale projects constitute just 10% of new supply. Similarly, on location, 65% of proposed projects are situated in Colombo. Opportunities for development therefore lie in the rest of the country; particularly in the North, East, and Central regions.

Inconsistent investment policies, particularly on land ownership, are a major sticking-point in Sri Lanka’s investment case. Alsoin need of attention are issues of air connectivity, domestic infrastructure and roads. Better connectivity is important in allowing Sri Lanka to benefit from its proximity to key feeder markets such as India and the Middle East. Finally, the expected termination of the “minimum room rate” in Colombo can be another important step in removing distortionary regulations.

Not for sale

Land ownership laws have a history of unpredictability in Sri Lanka. The past 24 months have seen a series of proposals, reversals and back-tracking that has left investors perplexed. Sri Lanka’s need for FDI-led growth is undisputed, yetthe position of current policydamages Sri Lanka’s attractiveness.

Whilst land ownership laws have always had restrictions, the current legislation, Land (Restrictions on Alienation) Act, No.38 of 2014, places a complete ban on the purchase of land by foreigners (individuals or companies with foreign shareholding of 50% or more). Foreign individuals may only lease land to a maximum term of 99 years, and must pay a lease tax of 15%.Perhaps most punitively, the law also stipulates that this lease tax is applied retroactively from 1st January 2013 and paid upfront on the total value of the lease.

Revisiting the legislation

In the 2016 Budget, the Finance Minister announced plans to reverse restrictions imposed by the new Land Act. Specifically, the restrictions on land ownership by foreign nationals are to be lifted, including the removal of the 15% tax on land leases and associated conditions. As at 1st January 2016, the tax imposed on leasing land to foreigners was removed; however, freehold ownership continues to be prohibited.

Reports in June suggest the government ismaking headway in deregulating the ownership of freehold land. Proposals include allowances conditional on nominal investments. Foreigners will be able to purchase government-owned lands for personal purposes on the condition that this comes with a $ 1,000,000 investment. 10-year temporary visas will also be made available for foreigners investing in excess of $300,000.

Is there a case for liberalising land ownership?

The case for foreign land ownership is contentious. Since land is a finite resource and a key factor of production, governments can be motivated to reserve its management and utilisation for locals. Of the plethora of rationales for controlling land, the most pertinent for Sri Lanka are that of economic control as well as security. Also compelling is the preservation of the ‘social fabric’ of communities.

Foreign-based speculation in land can be particularly disruptive in developing countries. The practise of buying up undeveloped land and ‘banking’ for capital appreciation can exaggerate the appreciation of land values and sometimes prevent development in the area.

On the other hand, some liberalisation of land ownership can be viewed as a positive step to enhance Sri Lanka’s push for FDI. Such a movecould signal a renewed commitment to a recovery in FDI inflows, which have suffered in the past 18 months.The ability to acquire property, with secure rights of ownership or lease, at transparent prices and with limited restrictions, is often considered an essential ingredient in investment decisions. Deregulationdoes not only encourage investment in land, but may more importantly alsoprovide an ancillary to investment in business. For example, land owned by an investor can be used as security for a capital raising.

The approach to land ownership of the majority of countries globally is that of an intermediate path. Restrictions are placed on land essential for “key sectors” such as designated areas for agriculture or mining. This introduces far greater flexibility than a complete ban on foreign ownership. In order to attract FDI flows into Sri Lanka, regionally competitive deregulation and policy consistency needs to be considered. Thailand and the Maldives each provide interesting comparisons (see Figure 3).

Creating the right environment

Whilst ostensibly Sri Lanka has seen progress in attracting major investment from outside players such as Hong Kong-based Shangri-La Hotels and India’s ITC Group, the reality is that these investments have transpired by circumventing the restrictions.

The majority of key investments from foreign players are undertaken through the Strategic Development Projects Act, which allows for the freehold of land as well as significant tax exemptions. Without these allowances, the Sri Lankan investment climate presents a far less attractive proposition that may not justify investments of this scale and risk. Sri Lanka is competing with other FDI destinations in the South and South East Asian region. In this context, stable policy and more flexible land allocation could encourage the investment needed to grow.

(Chantal Sirisena is a Research Assistant at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS). To view the article online and comment, visit the IPS blog ‘Talking Economics’ – www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics.)