Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Wednesday, 2 September 2015 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Sarah Hettiaratchi

Structural change is the process by which the distribution of economic output, the total of all sectoral shares with respect to a country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), shifts from one sector to another.

Typically an economy can be divided into three main sectors: agriculture, industry, and services. Usually when a country experiences economic growth and development its structure tends to change. With this structural change, the distribution of economic output shifts from agriculture to the industrial and then to the services sector.

Technical progress is seen as crucial in the process of structural change as it leads to the improvement in productivity of the industrial sector, and eventually leads to a reduction in the relative contribution of the agricultural sector.

Untypical pattern of structural change

In the case of Sri Lanka, the economy has not followed a typical pattern of

structural change even though its economy has experienced substantial development. Contribution of the agricultural sector to GDP has shown a decline relative to other sectors.

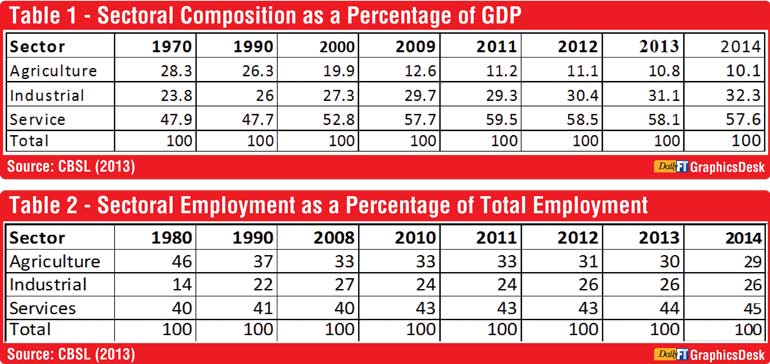

Table 1 indicates the sectoral contribution of each sector. However, the employment in the industrial sector is still less than agriculture (refer Table 2). This evidence proves that the productivity of the agricultural sector has not increased over a period of time.

The productivity in the agricultural sector has remained low due to the massive amount of subsidies given by the Government of Sri Lanka. When subsidies are provided, workers will remain in the agricultural sector itself and will not consider shifting as their costs can be covered even at a low level of productivity.

The support given to agriculture includes free water, the fertiliser subsidy and the guaranteed prices. This has meant that labour is being trapped in the agricultural sector despite low productivity.

In a typical rural agricultural sector, there can be underemployment of the workforce rather than unemployment, and the marginal productivity of agricultural labour will be zero at a certain point. This theory drawn up by Lewis states that, therefore, migration of labour out of agriculture does not reduce productivity in the whole economy. Labour can be released to work in the more productive and more urban industrial sector.

Industrialisation is promoted, due to the increase in the supply of workers who have moved from agriculture (Lewis, 1954). Higher productivity will be generated, resulting in higher profitability. This fosters capital accumulation together with innovation and economic development.

It is important to observe the historical evolution of economies and how the modernising economies have moved successfully from a subsistence self-sufficient agrarian economy to traditional light industries, then to the heavy- duty and high-tech industries and ultimately to the post-industrialisation phase which sees the predominance of the modern services sector.

Economic development can be understood as a continuous process of innovation and blended with superior technical know-how leading to production of low cost goods and services but yet with enhanced quality.

Secondly, economic development can be also interpreted as a dynamic process of industrialisation along with structural change which produces a diversified range of goods and services. At different stages of an economy’s development, economic structures may tend to vary due to differences in the country’s factors of production. Also known as factor endowments, these may regulate the pattern of output as well as relative prices.

The structure of economic resource endowments determines what sort of an industrial structure is needed for a country. For a developing country like Sri Lanka, it is important to have advanced resource endowments and an improved endowment structure. For this, physical and human capital should be upgraded.

Developing countries should adopt advanced technologies that provide with a comparative advantage and are compatible with the level of development in their economy. This is because, when the firms in the industry becomes competitive and when the factor endowment structure becomes diversified it creates a larger market share. The larger the market the greater the possibility of gaining economic surpluses in terms of profits and salaries.

As the economy now accumulates human and physical capital and with a diversified factor endowment structure, capital becomes cheaper and abundant. Eventually production shifts from labour-intensive manufacturing to more capital-intensive production.

Drivers of structural change not manufacturing but services: Policy implications

The developed nations and the successful emerging economies have traditionally achieved sustainable growth through manufacturing activities which were also regarded as the prime sources of innovation and technological change. The use of advanced technology, like computers, and semiconductors, in the manufacturing sector has reinforced the predominance of innovation in this sector.

On the other hand, Baumol’s (1967) study on the service sector was based on the belief that this sector was characterised by limited innovations and technical change. However, the ICT revolution and more recent advances in robotics and 3D printing, have demonstrated that this does not have to be the case.

However, it is important to understand that the South Asian experience in economic development and structural changes has been different. In both Sri Lanka and India, services rather than manufacturing have been the main driver of structural change and growth. This raises important public policy issues regarding Sri Lanka’s future development strategy, particularly as it has a relatively small domestic market and narrow resource endowment.

There is clearly scope to increase agricultural productivity. For this, there needs to be a review of land-use and crop-mix. In addition, the prospects for technological advances need to be explored. In addition, opportunities for niche manufacturing, where Sri Lanka has a comparative advantage, should be sought.

The services sector has demonstrated the greatest growth potential. As a result, priority should be attached to policies which incentivise a move from an economy characterised by low productivity agriculture/low technology manufacturing/traditional services (retail/wholesale trade; transportation/communications and public administration) to a modern economy based on higher productivity agriculture/higher technology manufacturing and especially developing modern services, such as ICT/BPO/KPO; aviation; as well as financial/health and education services.

One may conclude that Sri Lanka does not have to follow the classical trajectory of structural transformation cited in the literature. It can pursue a service-led development strategy. However, one should not ignore opportunities in agriculture and manufacturing based on the country’s resource endowment and comparative advantage.

In formulating future development policies Sri Lankan leaders need to take into consideration that the existing structure does not provide incentives to attract basic assembly-type industries which have to be competitive with our South Asian neighbours. Therefore, the emphasis should be on upgrading the tertiary and technical education to develop human resources which can take on high value manufacturing and other knowledge-based industries.

At the same time, taking advantage of Sri Lanka’s strategic location, there is need for accelerated actions to create a conducive environment for promoting service sector activities. These factors hopefully will be addressed by the policy makers to develop the future strategies of the new Government. The specific nature of the changes in the structure of the Sri Lankan economy should inform a thinking of the policy makers.

(The writer is an intern at the Pathfinder Foundation. Your views and comments are welcome at: www.pathfinderfoundation.org and [email protected].)