Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Friday, 3 March 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Shafraz Farook

The majority of us living and working in Colombo take access to decent, usable toilets for granted. That is until we venture out of our regular routes. Finding a toilet can be a daunting task even in Colombo, but not impossible. A number of eateries, malls and shopping arcades offer much needed refuge to those who are desperate to answer natures’ calls.

When we venture out of the city, it is a different story altogether. There is of course the ‘roughing out’ when we go camping, but when it is a busy population centre and you cannot find a decent toilet, you have to question Sri Lanka’s progress as a ‘fast developing’ country. If we were to extend that same question to a residential level (concerning households), what would the outcome look like?

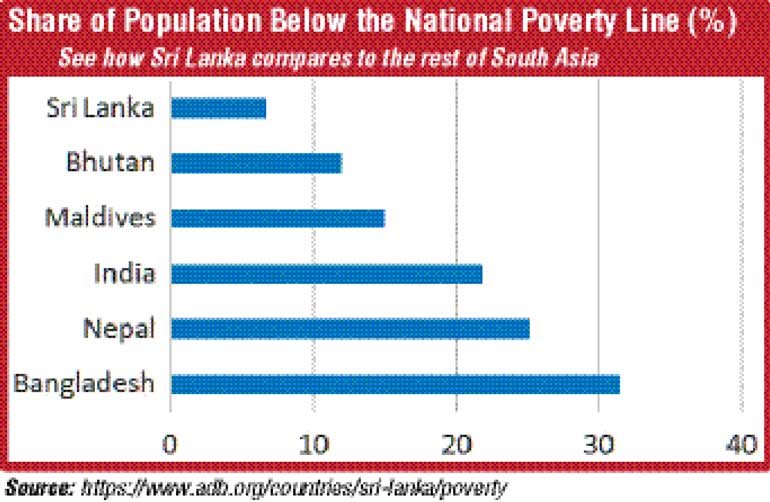

Sri Lanka is doing remarkably well as a middle income country and compared to its South Asian counterparts. Poverty is among the lowest at 6.7% compared to Bangladesh which is at 31.5% (adb.org/publications/basic-statistics-2016). We also pride ourselves with having a literacy rate of 92.63% (Ministry of Higher Education, SL), which is above average by world and regional standards.

We even score a remarkable 86 to 92% (depending on whom you quote) for access to sanitation in Sri Lanka. But, as a UNICEF Fact Sheet on Water, Sanitation and Hygiene states, “these figures mask considerable disparities and a need for customised solutions in underserved geographic locations, including remote rural areas, the plantation sector and pockets in the north and the east of the country.”

Not having access to proper toilets in underserved geographic locations is a given and yes we have a long way to go. But, the question we need to ask ourselves is if we are content with the access to and the quality of the toilets found even in busy city centres and residential areas around Sri Lanka.

Two issues that we are trying to discuss here (are being looked into, firstly the). Firstly, residential access to proper sanitation facilities and the second, (secondly the availability of) public toilets around Sri Lanka.

The discussion about residential access to sanitation emerged after at a recent meeting with the team at Reckitt Benckiser, the company that markets brands such as Harpic, Lysol and Dettol, on the day the Sigiriya toilet story first made news.

The situation in Sigiriya did not come as much of a surprise, but we were surprised to hear that a significant number of homes even in the Colombo District, lacked access to toilets. Especially when you consider that this segment is excluding the slum dwellings around Colombo, which have their own set of issues along with access to toilets.

The team that markets Harpic, Sri Lanka’s most popular toilet cleaning brand, has visited an estimated 250,000 households annually, over the past 10 years, educating residents on hygiene, proper sanitation and health. During the visits, covering a significant part of the island, the team found that some homes did not have a physical structure for a toilet or did not have a toilet at all. This reinforces the statement made in the context of the UNICEF Fact Sheet on Water, Sanitation and Hygiene report.

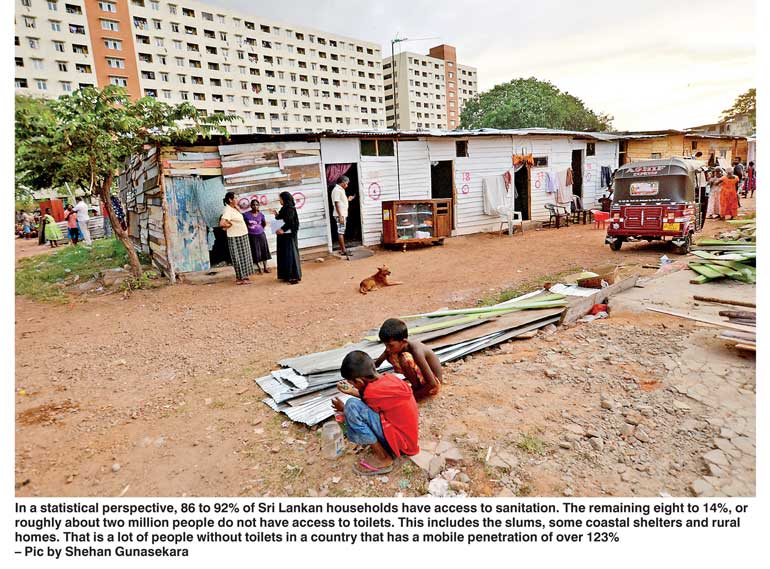

The quality of sanitation is a subjective one and cannot be addressed singularly; that is without discussing access to proper housing, poverty, etc. However, if the question is ‘have we moved away from open defecation to using some form of a toilet?’ The answer is a resounding yes. In a statistical perspective, 86 to 92% of Sri Lankan households have access to sanitation. The remaining eight to 14%, or roughly about two million people do not have access to toilets. This includes the slums, some coastal shelters and rural homes.

That is a lot of people without toilets in a country that has a mobile penetration of over 123%.

In the last 10 years or so, Sri Lanka has installed a number of public toilets, replacing or giving the public an alternative to the ones built under colonial rule. Most are fee levying and offer reasonable standards. And reasonable in this instance is dripping from the walls wet, musty and lacking toilet paper (with the exception of a few). Altogether it’s not so bad, but breaking it down – we have swaths of spaces with no toilet in sight or ones that could take the award for worst toilet in the world (a few school toilets fall into this category as well).

Take for example, the railway stations or the Pettah bus stop, anyone within a few hundred meters will know exactly where the toilets are. The southern expressway, bless the soul who did it, has a rest stop with decent, regularly maintained toilets. Most main roadways around Sri Lanka have toilet facilities as well and in usable state.

The malls in Colombo, including the refurbished old venues around Independence Square and Kandy have toilets. Are there toilets in the Galle Fort for instance or in local shopping districts such as Nugegoda or Maharagama? I know there are toilets at the Nugegoda supermarket, but cannot comment on the state of them.

Sigiriya is among a long list of significant places that are patronised by locals and foreign visitors on a regular basis that lack proper toilet facilities. Other places include at the higher elevations of Adam’s Peak, festival grounds and even some schools. Schools, especially rural schools that even lack basic classroom infrastructure, face a serious issue with access to water and sanitation.

Then there is the issue of why the public toilets got so filthy in the first place; the people using the public toilets. The common consensus here seems to be that it’s not each users’ responsibility to leave it in a state usable by the next person. The assumption we have to make here is that either people have no awareness about hygiene or just don’t care about it.

Below ground

Below ground

While the surface situation is very worrying, the little firsthand data available from the Harpic team indicates an even more worrying situation below ground. The team also noted that some toilet pits were improperly constructed, possibly leading to raw sewage contaminating the water table and on the surface affecting our health.

Exposure to raw sewage can cause fever, abdominal pains, diarrhea, vomiting and sometimes death. Campylobacteriosis, salmonellosis and typhoid fever are among the many diseases that can be caused by coming into contact with raw sewage (reference.com/science/effects-exposure-raw-sewage-a1e5fa181311588f#).

From available published information, it is understood that only about 500,000 people in the Colombo area, and between 1.9-2.6% of Sri Lanka’s population overall, live on land with access to traditional sewers (eyesrilanka.com/2016/12/05/aged-sewer-system-worsens-wastage-disposal).

The households that did not have access to the sewers, used a below ground pit that accumulated the sludge. When the pit filled up it was either pumped out with a bowser and pumped into the sewage pipe system in Colombo or disposed of it in convenient, if improper locations such as a nearby forest, landfill, or farm field leading to significant health and environmental problems.

The article also quoted environmental engineer Dr. Missaka Hettiarachchi saying, “We have a lot of direct disposal into waterways, and this material is getting into wetlands, canals, and rivers in Colombo’s suburbs, both north and south.” He added that rivers are not immune to the influx of bacteria, as improperly disposed waste easily makes its way into ground and surface water.

The dumping of raw sewage into of oceans is an entirely separate discussion, too complex to discuss in this article.

Most will retort that as a nation, we have bigger issues to deal with, like racism, the state of politics, private medical colleges and the cost of living. Toilets are among a handful of topics that everyone acknowledges but does nothing about.

One of the sub targets of the United Nations Millennium Development Goals (MDG) is to have 100% access to sanitation by 2020, less than four years from now. Therefore, it is important to resolve this issue at a residential level at least, If not at a national level. Both the public and private sector could also play a greater role in infrastructure investment, hygiene education and general awareness on the issue. Access to clean sanitation facilities must be a basic need as we move towards being a developed nation. After all, no one wants to be in a shitty situation.

(Shafraz Farook is a former journalist and currently a Communications Consultant. [email protected].)