Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Wednesday, 22 March 2017 00:02 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By K. Nanayakkara

The data communicated by the Central Bank shows that inflation has been on the rise and the rupee has been losing against the US dollar, which some people think suggests a policy rate hike (contractionary monetary policy measures) to control inflation and appreciate the rupee. While monetary policy tightening is a tool to achieve such objectives we should look at that option in the given context for it to be right or at least cause no further damage.

The Monetary Policy Review: No.1 –2017 (available on http://www.cbsl.gov.lk/pics_n_docs/02_prs/_docs/press/press_20170207e.pdf) attributes the recent increase of inflation to taxes and adverse weather. The Monetary Board hopes inflation will be manageable with the support of supply side and demand management policies. With this statement and what we have witnessed through the news and experience, it is reasonable to identify present inflation as Cost Push Inflation.

The same press release further states that they will closely monitor macroeconomic developments and take corrective action if required while not specifying a threshold of action or nature, obviously as action will be contingent upon the combination of data. Further, during the latest visit of IMF officials, as per the article on the Daily FT of 8 March 2017, the IMF has advised the Government to stand ready to tighten monetary policy if inflation and credit growth do not abate. The inflation for February 2017 (CCPI YOY) was reported at 6.8% (CBSL Weekly Economic Indicators). These combinations have made some people speculate that the Central Bank will increase policy rates.

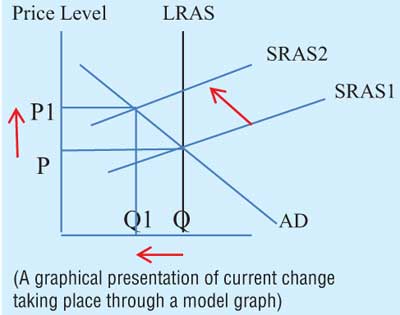

In economic terms the reason for present inflation as given by the Central Bank could be expressed as a shift in the supply curve to the left from the Long Run Aggregate Supply Quantity (LRAS). This could be graphically presented for an easy discussion (model graph available in many economics books).

What we see as inflation is the price movement from P to P1 caused by the reduction of output from Q to Q1 due to cost increases (tax) and natural causes in our context.

A contractionary monetary decision would give combined effects of reducing supply further (shift to left again) and cause further inflation while aggregate demand would also reduce as prices increase. The effects of previous policy rate hikes have definitely worked to contract demand and the economy. The slowing GDP growth rate and, as disclosed in the article by Dr. Rohantha Athukorala in the Daily FT of 15 March 2017, the halving of the FMCG growth rate, would be two testimonies.

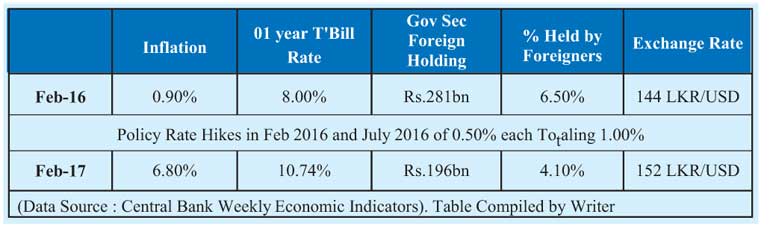

However, the main objectives of the policy decisions to control inflation and defend the exchange have not been met (refer table below).

On the other hand, if by any chance an expansionary policy is implemented then the economy would expand from its current level but cost a higher price level if the supply side is not corrected prior. Anyway now it’s a new agriculture cycle and the natural effects could be expected to fade off. So probably the monetary policy role in correcting the inflation issue might become less important while a better contribution could be made to increase supply back to normal levels through providing a subsidy or low rate/soft loans to the agriculture and SME sectors to source inputs or improve productivity. This strategy would directly address the cause identified by the Central Bank ‘supply side’ and correct the situation with no adverse effects on other economic aggregates.

It has become a common belief that when the interest rates are increased the exchange rate will improve. In fact the theory on monetary transmission says that when a country increases the interest rate, the exchange rate ‘may’ (Yes it’s ‘may’, this writer has not come across a formula linking the rate hike and the percentage increase of capital flows into the country) improve as there could be an investment flow into that country.

Apart from books on economics, this was found in a Bank of England paper in response to the suggestions by the Treasury Committee of the House of Commons and the House of Lords Select Committee on the Monetary Policy Committee of the Bank of England. It uses the word ‘probably and not ‘will’ on funds inflow (http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/other/monetary/montrans.pdf) and Working paper No.06-1 of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston also discuss the monetary transmission (https://www.bostonfed.org/publications/research-department-workingpaper/2006/the-monetary-transmission-mechanism.aspx).

They state that the initial appreciation happens with an inflow or shift of capital towards the country which will be followed by a depreciation of the currency in the future (of course due to interest rate parity).

The question we have to ask is will we see and has it happened in the past that when we increased interest rates, have foreigners rushed to invest with us. While the answer is ‘no’ (refer table below), in fact the total foreign holding in our Government securities has gone down. The argument of capital flows is proving true today for the developed countries as we saw the reaction of world markets to the Fed rate hike but not with our economies.

While the capital flows are missing when we increase interest rates, the interest rate parity is very much at work on our exchange rate as we see. The interest rate parity (arbitrage free/covered) states that the forward exchange rate will be adjusted according to the interest rate differentials of the two countries (to avoid any arbitrage gains). This is how the forward premiums/discounts are  calculated by bankers for forward rate quotes. Therefore we can see that if the US one-year treasury rate is 1.05% pa and our one-year rate is 10% pa, the spot exchange rate at 154 LKR/USD would mean that in one year the exchange rate will be 167 LKR/USD while if we increase our one-year Treasury rate to 12% the exchange rate would be 171 LKR/USD. We have been depreciating our currency with each rate hike given in the past, while the initial flow of capital was absent to appreciate the currency initially.

calculated by bankers for forward rate quotes. Therefore we can see that if the US one-year treasury rate is 1.05% pa and our one-year rate is 10% pa, the spot exchange rate at 154 LKR/USD would mean that in one year the exchange rate will be 167 LKR/USD while if we increase our one-year Treasury rate to 12% the exchange rate would be 171 LKR/USD. We have been depreciating our currency with each rate hike given in the past, while the initial flow of capital was absent to appreciate the currency initially.

It could be observed that today the one-year Treasury bill auction rate is 10.74% pa and the one-year T-Bond bid is at almost 11.30% pa (http://www.cbsl.gov.lk/pics_n_docs/_cei/_docs/ei/wei_2017.03.10.pdf) as per the Central Bank data. While the auction rate would also have a risk premium for uncertainty (as explained by an extension to the Fisher equation: Nominal Return sought is a function of Real Return, Expected Inflation and adding to it a Risk Premium (Interest rate risk in this case), the secondary market seems to ask for a even higher premium because the market participants are talking about a rate hike in the near future. When interest rates increase the Central Bank has to raise funds at a higher cost and the general public has to bear this increased cost in the form of taxes to be paid now or later.

A contractionary policy would dampen the economy further and it would continue to increase inflation, weaken the exchange rate and increase the fiscal deficit or increase taxes in this given state of our economy as the cause for the upsets is not from a demand side but a supply side. Similarly it is not the setting for an expansionary policy either. So probably the Central Bank has to build confidence in debt providers to take off the extra risk premiums sought through consistency. When the interest rates and exchange rates are stabilising and some policy consistency is seen, it would provide new opportunities for foreign investors to come back to our market and also for more local participation.

The other corrective measures would need to come from more specific action rather than general action. The specific actions could include providing incentives to sectors of the economy which are struggling (such as agriculture), further controlling certain imports (the list has to be decided by the authorities) through administrative and tariff measures where the consumer would look at foregoing or delaying consumption of such imports or substituting with local brands to give some space for the exchange rate to strengthen.