Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Tuesday, 22 December 2015 00:05 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Krishantha Prasad Cooray

One year ago, around the time of Christmas, there was tension in the country. The people were about to vote in a Presidential Election which would decide the destiny of the country, one way or the other. Today, one year later, we are celebrating Christmas and enjoying the festive season without any of these tensions.

A few weeks from now, we will see President Maithripala Sirisena complete one year in office. The anniversary will no doubt prompt many to step back and assess; promises made will be re-visited. The achievements will be listed. The tasks not attended to or those over which there was palpable stumbling will be noted. These analyses will be coloured by political loyalties. The more detached commentators will consider the contexts and their changing nature. Priorities as well as available resources will be factored in. In any event it is a necessary exercise for both the analyser and the analysed.

A revolution

Many have called the 8 January victory of Maithripala Sirisena over Mahinda Rajapaksa a revolution. This choice of word has been inspired no doubt by the popularity, despite the dictatorial style, that the ex-President enjoyed and also the distinct advantages of being an incumbent. Some of those advantages were from the Constitution and some from amendments to the same which he got Parliament to pass, clearly using his executive powers. There was also the will to abuse state resources over and above the general intimidation of opponents that had become normal for those in power, especially the Executive President. Considering the odds, therefore, ‘revolution’ was a legitimate word to use.

However, as history has shown many times, whether or not a revolution has indeed taken place has to be judged by the transformations that have taken place or have not as the case may be. New wine in old bottles does not go with the word revolution. It takes a lot of effort to overhaul a corrupt or inefficient system; a lot more than a change at the top even if it is supported by putting new faces in place of the old. Also, such change has to be supported by active participation of the people. They have to push and they too have to pull their weight.

In short, it was an ambitious task from day one. Expectations were naturally high. Skill did not always match enthusiasm. The resilience of the system, perhaps more than those who resented or wanted to throw spanners in the wheels, surprised many. The people were impatient at times, but at times understanding. As always, promises tended to be inflated versions of what was deliverable. Priorities and challenges saw certain areas being neglected. A lack of human resources was always going to be a problem. Mistakes would be and indeed were made. Some of it was of course forgivable, but there would be critics who would be unforgiving.

Assessing Maithri’s first year

In assessing the first year of what might be called the post-Mahinda era, we have to take all this into account. However, if it was about transforming a system for the better, then it is best to see how actions (or inaction) could impact the long-term (of the country) rather than the day-to-day lives of people.

To quickly go through the short-term elements, there will be complaints about the cost of living. We also saw protests regarding certain elements of the Budget. It must be understood that Sri Lanka is tied to a global economy and that the larger processes have been marked by one financial crisis moving to another. There are external factors that we can do little or nothing about. It must be said, however, that hard decisions have to be made. Short-term sacrifice is often necessary for long-term gain. If the sacrifices are unbearable and people protest against some of the harsh measures, then governments have to consider their voices. This was done in this instance. It should not be seen as a weakness but as a strength. This has to be appreciated. Economists will be able to and should look at the final version of the budget that Parliament passes and assess if indeed it is reasonable to hope that the country would be somewhere close to where the Finance Minister promises to take it come 1 January, 2017.

Justice takes time

There is displeasure in some circles about perceived slowness in bringing to book, people who have perpetrated financial fraud. It was expected that a lot of high-ranking persons in the previous regime would be put behind bars immediately after President Maithripala Sirisena took office. That this did not happen might be frustrating but then again when the wheels move too fast, justice can get derailed. If change was what was wanted, the old ways cannot be used to get desired results. The rule of law has to prevail and not be manoeuvred politically.

In terms of one aspect of the ‘short-term’ there can be no doubt. There is a sense of freedom to oppose that was almost non-existent during Mahinda Rajapaksa’s tenure. There is a greater faith in the institutions of justice. The consequent relief is palpable. Of course, one must not forget that it was during Mahinda Rajapaksa’s tenure that the other great fear – terrorism – was defeated. Some would say that things actually got worse after that. In any event, the defeat of terrorism did not see a consecration of the rule of law. Rather, that aspect got worse. The 8 January result gave hope to people that this would get corrected. Even before the independent institutions were set up, a healthier environment was created in this respect.

The political grouping that led to President Sirisena’s victory and the National Government that was formed after the General Election on 17 August are both marked with the term ‘good governance’ or in common parlance ‘Yahapalanaya’. That was an election promise that has since become an identifier, if not for the substance of what’s happened over the past 12 months for the constant use of the term. In political terms, the importance is that it refers to structural and therefore more sustainable changes that make ‘revolution’ a legitimate term.

The 100 days program was very clear about constitutional change. The 19th Amendment would help re-democratise Sri Lanka. Some interpreted Maithripala Sirisena’s manifesto as a promise to abolish the executive presidency. The 19th pruned some of the powers. More importantly it won back a lot of ground lost in the passage of the 18th Amendment, especially the Constitutional Council and independent commissions covering a wide range of spheres. The purpose was to allow institutions and officials to act without bending to the will of politicians, but guided only by well established rules and regulations. It took more than 100 days to institute the Constitutional Council, but it was done. It took more than 100 days to establish the independent commissions, but it was done. The benefits will of course be seen later rather than sooner, but one thing is clear: the way things get done in the country will no longer depend on the whims and fancies of the powerful. Men and women of integrity will ensure that established procedures will be followed.

The 20th Amendment, that of changing the electoral system, was to be passed within the first 100 days of President Sirisena’s term. It is disappointing that this did not happen. However, the idea has not been abandoned. Since the independent Delimitation Commission has been established we can expect greater movement in this regard. The same can be said of the Right to Information Act, which is a key piece of the puzzle to democratise Sri Lanka. It hasn’t yet seen the light of day, but the signs say that it will come up very soon. The most important aspect of these initiatives is that it helps create a level playing field where even the architects do not enjoy any special advantages.

There’s still work to be done

The work, however, is not complete. We are almost a year into this ‘revolution’, but we have to see the year that has passed as well as the several years to come as the gestation period. The cement of democracy must harden and this takes time. It requires that we do not disturb the mortar by straying into it carelessly. The leaders must be cautious and the citizens must be patient. Most importantly, those who are serious about real change have to make informed choices every step of the way that support not detract from those forces committed to and capable of seeing the reform process to the end.

As things stand, even the most ardent supporter of the ‘National Government’ would have to admit that we are yet to get the political stability necessary for sustained structural reform. In any given political context a coalition of the two main parties comes with tensions and generates uncertainty. We can debate the merits and demerits of the decisions which brought us to where we are now, but we can safely say we are on the correct track. Also, we can say that with all the tensions and uncertainty, and despite the push and pull of political forces within the constituent parties of the ruling coalition, the leaders have succeeded in instituting important changes. We already mentioned the 19th Amendment and the independent commissions.

The problem is that in these teething-years we need an enlightened and politically secure stewardship. It is hard to predict the course of politics in a democracy that has unfortunately been crippled to fledgling status. President Sirisena is walking a tightrope as leader of a party that actually campaigned against him. The still considerable powers vested in his office will guarantee that he retains control of reins tight enough to stop his party from pulling in different directions and thereby compromising his ability to maintain the integrity of the coalition government. It is important that he has this power because this alone can ensure the two-thirds parliamentary majority necessary for the passage of important constitutional amendments. The hopeful will assume as they should that he will keep the SLFP afloat, so to speak, at least until constitutional errors are corrected.

Abolishing the executive presidency

President Sirisena has maintained that he will be a one-term President. Also, he pledged at the funeral of Ven. Madoluwawe Sobitha Thero that he will see to it that the executive presidency is abolished. The President’s credibility rests on doing this immediately. If he waits until the tail-end of his term it might be interpreted as a move designed to obtain political advantage and not as an act by a statesman. Whether he will retire from politics at the end of his term is something President Sirisena will have to decide. If electoral reforms are instituted, then in a context where executive power returns to a Cabinet headed by the Prime Minister, it is imperative that the reins of power are with someone who has the vision and the ability to oversee this delicate period where the country progresses to a fully-fledged democracy built on the solid foundation of constitutional guarantees and insured by a citizenry that can no longer be kept in the dark because key information cannot be withheld.

Backing the right candidate

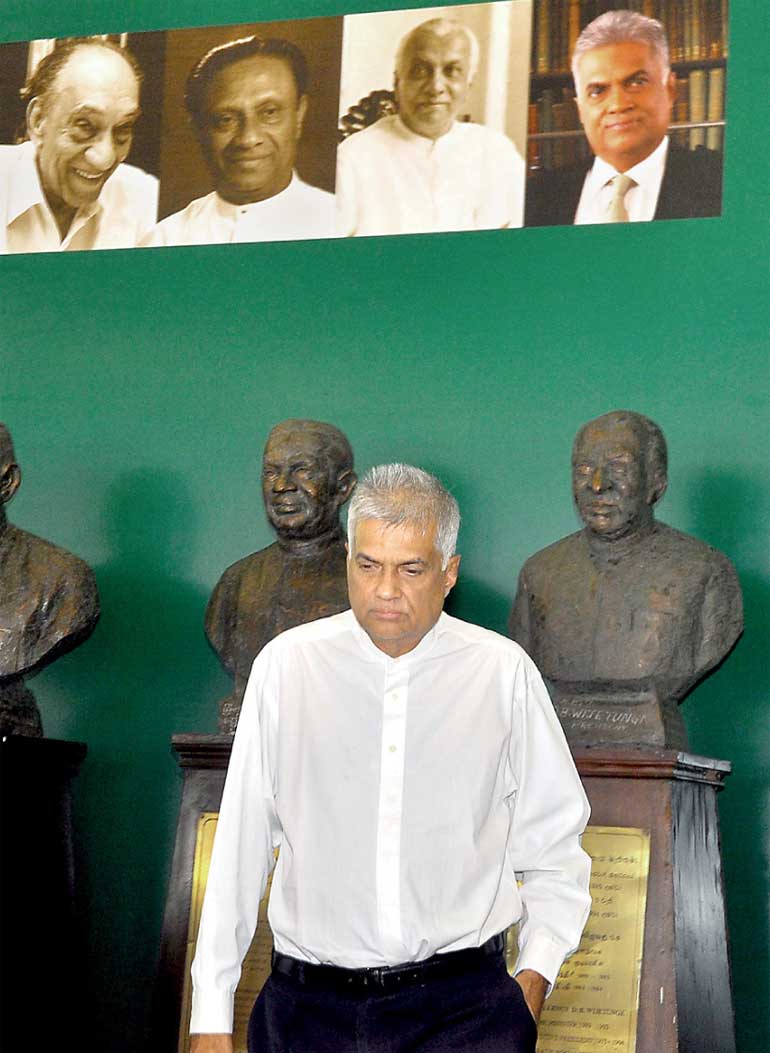

It is considering all of the above that we have to speak of the Leader of the United National Party, Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe. It has been argued that it would have been difficult to defeat Mahinda Rajapaksa had he and not Maithripala Sirisena contested. Indeed, it is hard to claim that he most definitely would have attracted some 200,000 SLFP votes that he would have needed to defeat the incumbent. However, no one can deny that his decision to back Sirisena was decisive. Despite objections or at least displeasure from certain quarters of his party, Wickremesinghe continued to back the President’s reform agenda after the 8 January. It could also be said that he played a lead role and not a supportive one in this regard. In the very least it can be said that while the direction given by the President was crucial, as important was the backing he received from the UNP, support which Wickremesinghe and no one else was capable of securing.

Wickremesinghe, in a changed political climate, led the UNP to its first major election win in over 10 years. He failed to deliver a majority but in hindsight, considering the need to work with the President to get the parliamentary arithmetic right for reform, coming up short can be seen as a blessing in disguise. Had he not been interested in reform and instead playing for personal or even party stakes, he could easily have engineered the defection of the number of MPs needed to get 113 seats in Parliament. He did not. This shows both political maturity and statesmanship. He promised to help the President form a coalition Government and kept his part of the bargain. He would have known that the discolouration that the SLFP underwent during the previous regime would inevitably taint this coalition Government. He would have known and if not he would know now that part of the blame for the inevitable errors of the tried-and-failed would be placed at his door. He has, however, put reform ahead of all else. That alone shows his commitment to a different Sri Lanka with a different political and institutional arrangement.

Batting on a nasty wicket

It has to be understood that he is batting on a nasty wicket. Quite apart from not being in absolute control of the political equation, Wickremesinghe is hampered by the fact that he doesn’t have the kind of support cast that J. R. Jayewardena for example had in 1977. He has a bits-and-pieces team capable of the odd cameo but certainly not ‘Test’ material, to use a cricketing metaphor. On the other hand, now that he is Prime Minister, he has been saved all the headaches of intra-party rivalry. To date he has not shown any vindictiveness. In fact, he has given the one man who contested him for the party leadership, Karu Jayasuriya, an all-important role.

As Speaker, Jayasuriya is also an ex-officio member of the Constitutional Council and most importantly its Chairman. Wickremesinghe has placed his trust in Jayasuriya’s proven abilities here and recognised the role Jayasuriya played in the victory of a democratic and democratising concept developed largely by Ven. Maduluwawe Sobitha Thero. Jayasuriya coordinated these efforts. It’s a good and encouraging sign.

Most importantly, Wickremesinghe seems to have understood that he alone cannot bring about change. He could give direction and probably is the only person with vision, power and stature that we have at this point to lead this drive. However, he needs to work with his party as well as the other major political formation, the SLFP or a coalition led by the SLFP. He has shown an admirable willingness to take the bi-partisan path, putting aside all that he had to suffer at the hands of the SLFP or rather the SLFP-led regimes over the past 21 years.

We are not out of the woods yet. We need a road map and we need the courage to walk a difficult path where light at the end of the tunnel is so dim that it is barely visible. As things stand, Ranil Wickremesinghe appears to be the one individual who has a map and has the will to walk the talk, at least until the cement dries to the point that the foundation laid on the 8 January can hold a sturdy democratic edifice. It must be mentioned that despite accusations by opponents of being “Pro-West” Wickremesinghe is the only Prime Minister who has graduated from a Sri Lankan university. He is not a chest-thumping nationalist, but his record shows that he is a logical and not an emotional leader who has the country’s interests at heart.

All things considered, we are still in the infant days of reform and that’s inevitable, as we argued above. Infancy is a time of great vulnerability; all the more reason for patience.

The coalition is still intact, but no one will bet on it gelling into a single, solid political entity. Wickremesinghe, as the most senior politician in the country, the most experienced leader and the one individual who has vision and political will, has an unenviable task ahead of him. He has many easy ways out. He can be just another ruler and be successful too in terms of securing power for his party and himself. That will not make history remember him as a statesman. He has to take the difficult path and has to convince the people that it is for everyone’s benefit. That would be his challenge in the coming months.