Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Wednesday, 18 November 2015 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Eshini Ekanayake

Despite a compelling growth story, Sri Lanka is struggling to attract portfolio investment due to a weak fiscal position. It is early on in the new Government’s term, and with the 2016 Budget to be announced soon, the country is now at a pivotal point where it can make a decisive shift back towards a durable path of medium-term fiscal consolidation without risking electoral punishment

Weak fiscal finances currently the most pressing economic issue for Sri Lanka

Fiscal policy is considered to have the dual role of smoothing out business cycles in the short run, while meeting debt sustainability targets in the long runi. Given Sri Lanka’s position in the business cycle and the current accommodative monetary policy stance, the country does not require further stimulus in the form of expansionary fiscal policy in the short to medium term. The call for fiscal  consolidation thus remains valid. Addressing the weak fiscal situation, which is currently a credit weakness for investors, is therefore more of a pressing issue in Sri Lanka’s case, as it affects the economy on multiple fronts, causing macroeconomic instability. The favourable effects of a budget focused on fiscal consolidation are threefold for Sri Lanka:

consolidation thus remains valid. Addressing the weak fiscal situation, which is currently a credit weakness for investors, is therefore more of a pressing issue in Sri Lanka’s case, as it affects the economy on multiple fronts, causing macroeconomic instability. The favourable effects of a budget focused on fiscal consolidation are threefold for Sri Lanka:

(1) Aiding in lowering Government treasury yields and reducing the Government debt burden, in turn positively affecting Sri Lanka’s abysmal fiscal position.

(2) Limiting the BoP deficit and reducing pressure on the exchange rate through increased foreign portfolio investments.

(3) Leaving room for the Government to implement counter-cyclical policies in case a negative demand shock hits the economy in the future

Government credibility in question over missed deficit targets in

recent years

Most governments veer away from the fiscal adjustments required for fiscal consolidation due to the political risk involved. Even when they do attempt them, targets are missed, as the quality of forecasts is poor, leading to an overestimation of revenue collection and an underestimation of expenditure. In Sri Lanka’s case, a budget focused on fiscal consolidation has most often been attempted through significant increases in revenue targets and modest cuts in recurrent expenditure.

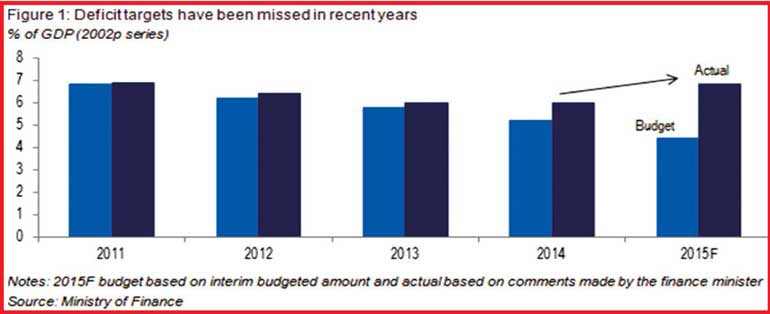

However, Sri Lanka’s revenue collection has been on a declining trend, with Government revenue at 12% of GDP in 2014 compared with 17% in 2005 (under the 2002p GDP series). This has led to missed deficit targets in recent years (figure 1), which in turn has affected Government credibility. 2015 will be no exception, as the first half of the year saw total revenue at only 39% of the total annual budgeted estimate (a.b.e) and total expenditure (recurrent + capital) at 49%. A closer look at the numbers show that the current-account deficit in the budget for 1H-2015 is eight times the budgeted (a.b.e), while the overall deficit was 80% the budgeted (a.b.e). The current-account deficit has shot up due to excessive recurrent expenditure this year on higher wages and transfers and a low level of tax collection and non-tax revenue (42% and 25% of the budgeted, respectively).The overall budget deficit has therefore been contained at 80% at the expense of capex, hurting public investment, which is necessary for spurring long-term growth. Accordingly, the finance minister announced that the overall deficit is likely to reach 6.8% in 2015, much higher than the interim budget target of 4.4% for the full yearii.

Weak fiscal position affects debt sustainability, interest burden, and credit rating

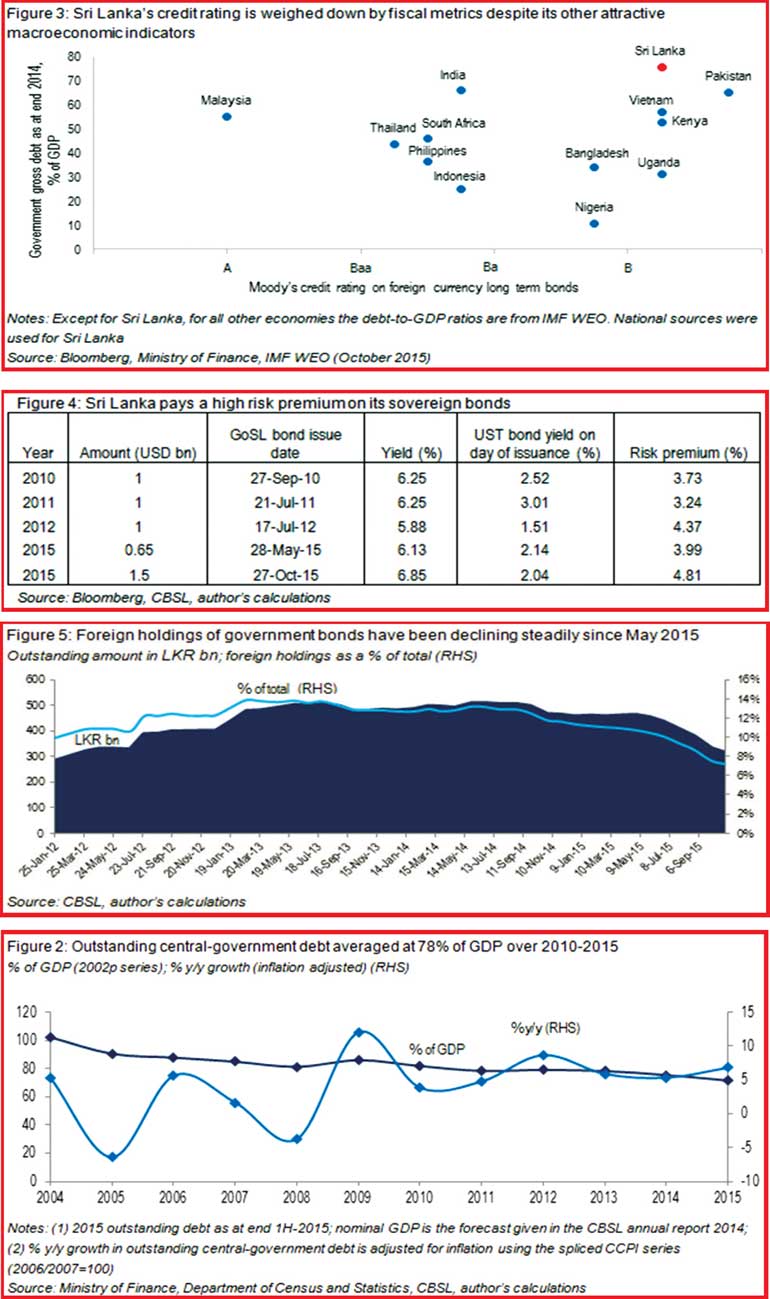

Sri Lanka’s high public debt and interest burden is a cause for concern, and would continue to grow if the Government persists in adding to its deficit (figure 2) each year. Central-Government debt averaged at 78% of GDP over 2010-2015iii, with inflation-adjusted public debt growing at a CAGR of 6.3%iv over the same period. Further, 21%-23% of total Government expenditure alone has been used to finance interest costs, leaving less room for Government expenditure to be allocated for the social and physical infrastructure that is necessary to boost Sri Lanka’s potential output.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) recommends a public-debt level of 40% of GDP as prudent for emerging economiesv. The IMF argues that when public debt gets very large, the Government will find it difficult to generate a primary fiscal balance (budget balance net of interest payments) that is sufficient to ensure sustainability, and that a surprise negative shock to the economy can push a country beyond its desired debt limit. The advice is therefore for countries to remain at or below the debt limit of 40% to ensure prudence; Sri Lanka should aim to achieve this in the long run.

Sri Lanka’s weak fiscal position has repeatedly been highlighted as a major credit weakness by all three of the big credit-rating agencies. Despite Sri Lanka’s compelling factors that bode well for markets, such as its robust GDP growth, attractive growth-inflation dynamic, relatively high GDP per capita, and strong social-economic indicators, its credit rating is weighed down by its fiscal metrics (figure 3).

The weak fiscal situation is also a factor for the Government’s high funding costs, as evidenced by the high risk premium the country pays on its sovereign bond issuances. Sri Lanka tapped the international bond market this year for the second time with a benchmark sovereign bond issue of USD1.5bn. Notwithstanding the volatile global economic conditions this year that have led to an increase in sovereign-bond yields across emerging markets, Sri Lanka’s USD1.5bn 10-year issuance saw a risk premium of 4.81%, the highest so far since Sri Lanka’s issuance of 10-year USD bonds in 2010 (figure 4). Had Sri Lanka brought down its public debt levels further and been committed to the path of fiscal consolidation, the Government would have been in a better position to tap the international bond market at a lower yield level this year, despite prevailing market conditions. Therefore, a credible fiscal-consolidation plan will aid in improving Sri Lanka’s public debt position, which in turn will support in keeping funding costs down in spite of issuance.

Low investor risk appetite weighing heavily on Sri Lanka as a preferred destination for capital inflows

Given that Sri Lanka is now a middle-income economy with less access to bilateral and multi-lateral donor funding at concessionary rates, it now needs to attract portfolio investment into the country’s bond and stock market to boost its foreign reserves and bridge its budget deficit. A healthy inflow of foreign capital will aid in financing the twin deficits and could ease pressure off the currency while improving foreign reserves, making the country less vulnerable to external shocks. Fiscal policy has a significant role to play in attracting foreign portfolio investment, and this is especially true during times of market stress, as investors tend to monitor emerging and frontier markets that have relatively high public debt and low levels of foreign reserves, as the knock-on effects of greater outflows can make these economies more vulnerable to external headwinds. This year represents such a period, with Sri Lanka experiencing high levels of capital outflows since May, along with other emerging and frontier markets, as a result of an impending rate hike in the US and a slowdown in China. Foreign holdings of Government securities fell by Rs. 142 b since the beginning of the year to Rs. 311 b as at end-October 2015, the lowest level seen since February 2012. This saw foreign holdings fall to 7.2% of total outstanding Government securities from 11.2% at the beginning of the year (figure 5).

With overall risk appetite deteriorating for emerging- and frontier-market debt, Sri Lanka needs to improve its risk-reward dynamic within its peers in order to attract capital inflows. Re-committing towards fiscal consolidation and ensuring budget credibility will support this cause. It will not only enable Sri Lanka to limit its BoP deficit, but also deepen its capital markets and bring down Government treasury yields.

A number of studies conducted by the IMF suggest that an increase in non-resident ownership of domestic local-currency debt in emerging economies has been a significant factor in reducing long-term Government yields (Peiris 2010, and EBeke and Lu 2014)vi. Thus, increased foreign holdings of Government debt push up prices and keep yields low, in turn allowing the country to borrow for cheaper. However, a very large holding of Government debt by foreigners has its caveats – in times of global-market stress, it can leave a country more vulnerable to global financial conditions; the effect can, however, be minimised if the country remains a relatively attractive destination compared with its peers by having strong positive economic fundamentals.

Ensuring success – the importance of timing to minimise electoral punishment and the need to trim recurrent expenditure (as opposed to capex)

There has been much emphasis on the need for radical tax reforms in the country to improve the Government’s revenue position; however, it is equally important to consider the effects of a slowdown in Government expenditure on the economy if it is on a path of fiscal consolidation. Since, the dynamics of how different Government-expenditure categories affect the economy can vary by their respective multiplier effects, it is important to design fiscal policy based on the assessments of these multipliers so that the response on GDP is as intended. On the one-hand, it is difficult to accurately estimate multiplier effects, as isolating direct effects on GDP is a challenge in empirical research. On the other-hand, there is limited empirical research on Government-expenditure multipliers done for Sri Lanka. This would therefore provide an interesting area for academic research in Sri Lanka, as policymakers can use it when designing fiscal policy and projecting macroeconomics for the country.

Most studies on other emerging economies, however, have shown that public investment has the ability to crowd in private investment, contributing both to expenditure on the demand side and to capital stock on the supply side. Despite interest rates rising marginally as fiscal deficits rise on the effects of capital expenditure, it is overshadowed by the effects of public investment on private investment resulting in a much larger multiplier effect than recurrent expenditure. As such, it is advisable for fiscal correction to be carried out from the recurrent-expenditure side rather than through capex on social and physical infrastructure.

Ultimately, fiscal consolidation is unpopular. However, if a new government is serious about fiscal discipline, it could present a budget focused on fiscal consolidation at the beginning of its legislative term, in order to reduce electoral punishment and ensure success. Yes, the task will be gruelling, but success will restore budget credibility as well as investor confidence, which Sri Lanka desperately needs.

Footnotes

i IMF assigns this dual role to fiscal policy in their global macroeconomic model, “The global integrated monetary and fiscal model (GIMF) – Theoretical structure”, February, IMF working paper, 2010

ii It is unclear whether this number is based on the old GDP series or the new

iii 2015 outstanding debt was taken as at end 1H-2015, while nominal GDP (2002p series)is the forecast given in the CBSL 2014 annual report

iv Outstanding central-government debt is adjusted for inflation using a spliced CCPI series (2006/2007=100)

v Navigating the challenges ahead, Fiscal Monitor, IMF, 2010

vi Peiris, S. J. (2010), “Foreign Participation in Emerging Markets’ Local Currency Bond Markets,” IMF Working Paper 10/88; Christian Ebeke, Yinqiu Lin (2014), “Emerging Market Local Currency Bond Yields and Foreign Holdings in the Post-Lehman Period—a Fortune or Misfortune,” IMF Working Paper 14/29

(This article was prepared by Eshini Ekanayake in her personal capacity. The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of Copal Amba. The writer is Associate Vice President, Quantitative Research at Copal Amba Colombo. Copal Amba is the leading provider of offshore research and analytics services to the global financial and corporate sectors. It has consistently been ranked #1 in its space by multiple independent customer satisfaction surveys. Copal Amba’s clients include leading bulge-bracket financial institutions, Fortune 100 corporations, mid-tier companies, boutique investment banks, and funds. It supports over 200 institutional clients through its team of 2500+ employees and its 9 delivery centres are located close to its clients and in proximity to scalable talent pools. Copal Amba’s clients have saved over USD1.9 billion over the past 12 years, by using its services to enhance front office efficiency. Copal Amba is a Moody’s Analytics company. For more information, visit www.copalamba.com.)