Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Wednesday, 5 July 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

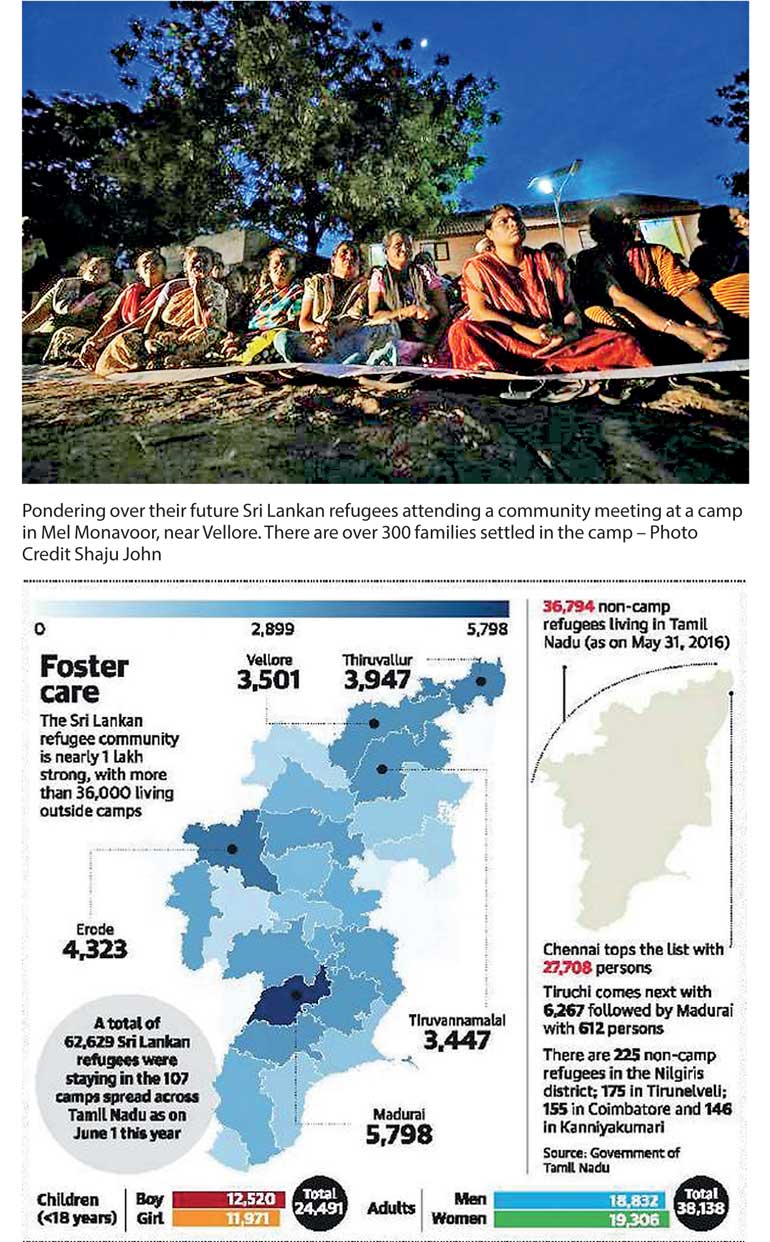

Eight years after the end of the war, Sri Lankan Tamil refugees, who have been in the State for decades, are still stateless persons. There are suggestions that the camps should be shut and refugees who are willing to stay back should be absorbed fully in Tamil Nadu while others can return to start afresh in the island nation

Eight years after the end of the war, Sri Lankan Tamil refugees, who have been in the State for decades, are still stateless persons. There are suggestions that the camps should be shut and refugees who are willing to stay back should be absorbed fully in Tamil Nadu while others can return to start afresh in the island nation

By T. Ramakrishnan

The Hindu: Ramesh was barely eight years old in 1990 when his parents, living in Vavuniya, Northern Province of Sri Lanka, had to flee to India along with him. Since then, he has been living in Gummidipoondi, on the northern outskirts of Chennai, at a camp meant for people like him and his parents — Sri Lankan refugees. The Gummidipoondi camp is one of the earliest to be set up in the State following the Black July of 1983, the anti-Tamil pogrom that took place across Sri Lanka.

He is conscious that the camp refugees — who have all been enrolled in Aadhaar — are getting the benefits of all the welfare schemes that the Tamil Nadu government has been implementing for the people of the State. Free rice, the provision of educational kits to school students, Moovalur Ramamirtham Ammaiyar Marriage Assistance Scheme and the Dr. Muthulakshmi Reddy Maternity Assistance Scheme are among the many. Recently, the Government announced that eligible women living in the camps at the time of their marriage would also be given an eight-gram gold coin, meant to be used for making “thali,” the sacred thread of marriage.

The Central and State Governments provide them cash assistance, which is INR 1,000 for the head of every family; INR 750 for every additional member of the family aged 12 years and above and INR 400 for children aged up to 12 years. The refugees too are covered under all the welfare schemes of the State Government.

Invariably, every family in Ramesh’s camp or, for that matter, in 106 other camps all over the State, owns many electrical or electronic consumer durables that can be found in any middle class home. It is the State Government that foots the bill for the electricity consumption of camp refugees.

Yet, Ramesh is sore about his status as a refugee. “How long should I live here as a refugee? I have spent the most productive part of my life here. In a matter of 12-13 years, my son, who is aged 13 years, will attain the marriageable age. Should he also be like me?” Ramesh, who has set up a small shop on the premises of the camp, has touched upon a complex issue – voluntary repatriation. And, he is not alone.

Twenty-five-year-old Kavitha Cruz and her younger brother, both inmates of a camp in Karur, in the central part of the State, are engineering graduates. Kavitha, now working in Chennai, says international companies and major IT firms insist that their prospective employees must have passports, which no camp refugee can have.

Thanks to the present scheme of the State Government, more and more students from various camps are pursuing professional courses with the possible exception of medicine. But, there is a catch.

Many, if not most, of them have little scope for getting the right jobs as they are virtually stateless persons. Ordinarily, they cannot acquire Indian passports because of complicated legal issues. “You have to go [back] to Sri Lanka to acquire your passport,” Kavitha observes, adding that she was barely one month old when her parents had to migrate to Tamil Nadu.

About 140 km northwest of Gummidipoondi lies the Abdullapuram camp in Vellore where many refugees are mentally prepared to go back to their native place – Mannar of the Northern Province. M. Selvaratnam, who came to Tamil Nadu in 1990, says there is a genuine eagerness on the part of members of his community to return to Sri Lanka. But, having lived here in Tamil Nadu for over 20-25 years, the refugees have acquired many movable assets, all of which cannot be transported by air if they choose to get repatriated under the aegis of the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

This is why “we have been seeking the resumption of ferry services between Rameswaram and Talaimannar,” says S.C. Chandrahasan, who has been running the Organisation for Eelam Refugees Rehabilitation (OfERR) for the last 34 years. Once the decision is taken to resume the ferry services, they can cover Kankesanthurai, also in the Northern Province, and Trincomalee in the Eastern Province. Besides, as the refugees generally hail from these two provinces, they would be put to hardship if they choose to go back by air as the existing air services are only up to Colombo, which is in the Western Province.

The process of voluntary repatriation is not going to be simple, even if the Governments of the two countries decide to move ahead. The number of persons involved is quite huge.

The community of Lankan Tamil refugees, living in camps and outside camps, is nearly one lakh. It is also well known that there is a substantial section of Sri Lankan Tamils living in Tamil Nadu that hasn’t been enumerated, even though its number is anyone’s guess.

At the same time, not every refugee is willing to go back. Sumathi of Abdullapuram in Vellore district says that those refugees, aged below 35 years, are not keen on going to Sri Lanka as they have got used to the Indian or Tamil Nadu conditions.

Pathinathan, a Tamil writer and a non-camp refugee, who had expressed, through social media, critical views of the Indian authorities for the state of affairs in the camps, articulates further. “Those who are willing to go back on their own should be encouraged to return.

Those who are not keen on going to Sri Lanka can be granted Indian citizenship. The camps, established over 30 years ago, have outlived their purpose. It is in everyone’s interests that the Governments of India and Sri Lanka come to an understanding on this issue at the earliest.”

The spectacular regime change, which took place in January 2015 and marked the defeat of Mahinda Rajapaksa and the victory of Maithripala Sirisena in the presidential election, appears to have created openness in Lankan society and freedom for the minorities in general and Tamils in particular.

Despite improvement in the conditions, Indian authorities don’t seem to be in any hurry to be proactive and take steps to speed up repatriation. “We will only facilitate those who are keen on going back on his or her own, though we do not even enquire whether they want to return,” say officials in charge of the refugees.

A few years ago, there was talk of the two countries entering into a memorandum of understanding but it died down subsequently, after some voices of protest emanated from some political parties of Tamil Nadu. Sri Lanka’s new Foreign Minister Ravi Karunanayake, in a telephonic conversation with this reporter, says “Basically, we have done what has to be done with regard to voluntary repatriation. We are ever-ready to take them back.”

Chandrahasan mooted the proposal in 2015 for a package of assistance to enable refugee-returnees to start smoothly their fresh innings in their home country.

He still feels that the Governments of the two countries can consider ways of assisting the refugees in some form to aid their return. Camps, despite the reasonable standard of living they offer, are not designed to be permanent solutions.

Life in the refugee camps has its own challenges. Many women, be they in Gummidipoondi or Abdullapuram, are of the view that alcoholism is quite rampant. “You tell the Government that they do not have to do anything else. Let them close down a nearby liquor shop,” says a woman of Gummidipoondi, who has a few growing grandchildren.

About a month ago, there was a report of the bus crew getting assaulted by some inmates of a camp in Bhavanisagar in the western part of Tamil Nadu for having reprimanded the refugees for misbehaviour. The authorities saw to it that the episode did not become more serious, an official in the Rehabilitation Department says.

There are also areas wherein the authorities are found wanting. Take the example of durable houses, built for them three-four years ago.

In Gummidipoondi, 96 such houses have been “completed” but they remain unoccupied. The roofs of some houses have blown off, thanks to Cyclone Vardah in December last. In the words of a government official, the roof’s material is “better than” asbestos sheet, which was provided in older houses. Apparently, there have been cracks on the walls of the recent houses. No house has a washroom. For that matter, there is no provision even for common toilets.

These 96 houses, each measuring 161 sq ft and costing INR 1.2 lakh, are part of a total of 1,202 houses that the State Government, in December 2013, decided to build. Of the total figure, 1,164 houses have been constructed. An official of the State Rehabilitation Department says that in respect of the remaining 38 houses which will come up in Namakkal, earth work is going on.

There is little information, however, on how many of the completed houses have been handed over to beneficiaries, as in the case of Gummidipoondi.

The local Tahsildar Sridharan, who was posted there three months ago, is candid in admitting that he has not yet visited the site, which is not far from his office. “That is not a priority item,” he concedes.

Pointing out that the houses were built through the Rural Development department, the official does not mince words about the disagreeable activities of some refugees living in the camp. It is because of such persons that the arrangements for power supply got disrupted and windows of some houses removed. “We will take steps soon to ensure that the supply is provided,” he says, adding that efforts will be made to keep the houses ready so that the intended beneficiaries can occupy the houses at the earliest.

But, Chandrahasan is not disheartened by the shortcomings of the Indian or Tamil Nadu authorities. “Nowhere in the world can you see the kind of hospitality as has been provided to Sri Lankan refugees,” he asserts. “So far, there have been no reports of locals misbehaving with the women of the camps.” An elderly woman of the Gummidipoondi camp endorses his point and says “if at all the women of the camp face any problem, it is because of insiders.”

The camps do offer a secure environment for these refugees, and moving from there to starting afresh in Sri Lanka may be a daunting task for people like Ramesh and Sumathi.

A key challenge would be getting back their land. Barring people of hill-country origin, those whose roots are from the Northern Province had owned lands before they fled to India for safety at the height of the civil war. It is quite likely that lands of some of them have been “occupied” by others.

Still, it is worth going back as one can lead the rest of one’s life in dignity — this is the sentiment that is operating in the minds of a section of refugees, whose number is, apparently, on the rise.