Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Saturday, 11 March 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By P.K. Balachandran

Sri Lanka’s relations with India is age-old and well known, given the fact that Emperor Asoka had sent his son Prince Mahinda and daughter Sanghamitta to the island in the 3rd Century BC to spread Buddhism. And it is also acknowledged that the Sinhalese, the island’s majority community, trace their origin to Prince Vijaya of Bengal, who arrived in the island with his entourage in 543 BC and stayed put. But while the Buddhist link is much talked about and written on, and is alive even today, the link with Bengal is not. Sri Lanka’s ties with Bengal had waxed and waned over the centuries.

Come Buddhism, Sri Lanka’s link with Magadha (in what is now Bihar) replaced that with Bengal because Buddhism came from Magadha, owing to the fact that Emperor Asoka ruled from there. With Buddhism came Pali, a Sanskrit based Prakrit (dialect) spoken in those parts at the time of the Buddha. Later on, when trade routes opened up between mainland India and Sri Lanka, and Buddhism became the religion of India’s overseas traders, North Indian traders, especially from seafaring Gujarat, developed close ties with Sri Lanka. One of the results was the Sanskritisation of the Sinhalese language which marked it from Dravidian Tamil which was the language spoken in the north of the island and in South India across the narrow Palk Strait.

It appears that for centuries, Sri Lanka had little or no contact with Bengal. On the other hand, Sinhalese kings had much to do in both war and peace with the Chola and Pandyan kingdoms in India’s Tamil country because of the rise in the political, military and economic power of these Tamil-speaking kingdoms. The Tamils had also become big time overseas traders to the extent of making Tamil the language of trade in this part of the world.

The Portuguese who ruled parts of Sri Lanka from the 16th Century, came essentially from the Western coast of India, stretching from Goa to Cochin. The Dutch, who followed the Portuguese in the 17th Century, also came from Cochin (and of course from Batavia or Java in present-day Indonesia).

But with the arrival of the British, came a radical change, though not immediately. The British-Indian Empire, which stretched across South Asia, had Calcutta in Bengal as its capital. With the consolidation of British rule in India and South Asia after 1857, the city of Calcutta became the nerve centre of political, economic cultural activity. Bengal, its culture and thoughts, set the standard in many ways. In the 19th and early 20th Centuries it used to be said: “What Bengal thinks today, India thinks tomorrow.”

And when the Bengali elite took the leadership in bringing about India’s cultural renaissance in the late 19th Century and the first part of the 20th as part of India’s freedom struggle, elements of the new Bengali culture began to influence cultures in the region. Sri Lanka could not escape the impact of this as British rule had re-built the island’s bridges with India.

It was Bengal which stirred and influenced nationalistic consciousness in the field of culture among the then highly colonised and Westernised elite of Sri Lanka, then known as Ceylon. During the age of Sinhalese cultural renaissance in the late 19th and the first half of the 20th Century, Bengali music and Bengali institutions were the models to follow.

The great Sinhalese-Buddhist revivalist, Anagarika Dharmapala (1864-1933) went to Calcutta to gather support among Bengal’s bhadralok (gentry) for the retrieval of ancient Buddhist places of worship in Bodh Gaya in Bihar from the clutches of Hindu mahants. Dharmapala headquartered his international Maha Bodhi Society at Calcutta. Rabindranath Tagore had contributed poems and articles to the magazine the Maha Bodhi Society was producing.

Tagore’s influence

Rabindranath Tagore was seen in Sri Lanka, not only as a messiah of political liberation from British rule, but a cultural liberator too. Inspired by Tagore’s unique educational institution, Shantiniketan, a Sri Lankan nationalist, Wilmot Perera, started a similar institution called Sri Palee at Horana in Kalutara District south of Colombo, where students studied and learnt dance and music in the open air and under the canopy of trees. In fact, it was Tagore who laid the foundation stone of the institution in 1934 and suggested that it be named Sri Palee.

An admirer of Theravada Buddhism, which is practiced in Sri Lanka, Tagore introduced Buddhist and Pali studies into the curriculum at the Vishwa Bharati University which he founded. Among Guru Dev’s followers in Calcutta were Sri Lankan students studying in Calcutta University including nationalists such as D.B. Jayatilaka, W.A.de Silva, and Rev. Rambukwelle Siddhartha. The renowned Sri Lankan art historian and cultural revivalist, Ananda Coomaraswamy, found in Tagore an ardent supporter.

Tagore had visited Sri Lanka thrice, 1922, 1928 and 1934 to rousing receptions in Colombo, Galle, Kandy and Jaffna. Described as a “Maha Kavi” in the island, his speeches in leading schools like Ananda, Mahinda, Trinity and Jaffna Central, were well covered in the media. When he staged his dance drama ‘Shap Mochan’ to packed halls over six days, S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike, a Prime Minister-to-be reviewed it in the Ceylon Daily News saying it was “a revelation of art at its highest”.

Tagore abjured political issues during his visits to Sri Lanka, preferring to stress the need to revive indigenous cultures among “those who, due to some unfortunate external circumstances, have forgotten their own past and are ready to disown their richest inheritance”.

And he did succeed in his mission. Sri Lankan art followed the style of Bengali artistes like Nandalal Bose, who had accompanied Tagore during his 1934 visit. Bose was to do paintings depicting the Kelaniya temple. Tagore was impressed with the slow and fluid Kandyan dance and got it incorporated into the Shantiniketan style of dancing. According to Dr. Sandagomi Coperahewa, Tagore’s praise for the Kandyan style helped it become the principal dance form of Sri Lanka.

The musical tradition of Shantiniketan had also found deep roots among the Sinhalese. According to Sri Lankan film maker Vimukthi Jayasundara, the tune of the Sri Lankan national anthem Namo Namo Matha was composed in Rabindra Sangeet style by Tagore himself, while the Sinhalese lyric was penned by his student, Ananda Samarakoon. Famous singer Sunil Shantha learnt music at Shantiniketan and playwright Ediriweera Sarachchandra had his philosophical education at Tagore’s institution. Dancer Chitrasena, the “Uday Shankar” of Sri Lanka, was also a product of Shantiniketan.

Tagore had tremendously influenced writing in the Sinhalese language. The noted Sinhalese writer Martin Wickramasinghe had said that Tagore had “encouraged young Sri Lankan poets to break away from traditional Sinhalese poetry”. Wickramasinghe went on to say: “The enduring appeal of Tagore to the intelligentsia of Ceylon is his attitude to religion and life which he exposed artistically in his poetry.”

Cinematic bridge

The earliest Sri Lankan feature films were mere copies of Tamil films made in Madras and Salem, as Tamils from India dominated the Sri Lankan film industry. But this changed in the 1950s with the international acclaim won by Bengali film maker Satyajit Ray’s realistic 1955 film Pather Panchali. Lester James Peries’ path-breaking Sinhalese film Rekhawa (1956) came a year after Ray’s Pather Panchali though Peries would attribute his style to the influence of European cinema rather than Ray. At any rate, after Rekhawa, Sri Lankan films were in the intellectual and creative league of avant garde creations emanating from Bengal.

However, as Bengal declined in India, yielding place to North India due to the shifting of business and political power to Bombay and New Delhi respectively, especially after India’s independence in 1947, the identification of the Sinhalese with Bengal waned and that with North India and North Indian music, dance and films grew. After the liberalisation of the Sri Lankan economy in 1977 and the entry of Western capital, Sri Lankan culture and tastes became Americanised.

But there are signs of a revival of indigenous forms now. The mounting economic and political pressure from Western nations over the human rights issue, has stirred nationalism and pride in indigenous cultural forms.

However, Sri Lankan indigenous forms are heavily influenced by India, including Bengal. After all, Sri Lankans and Indians belong to the same cultural pool. Rabindranath Tagore did not see this bond as being injurious to Sri Lanka as cultural ties with India are as old as Sri Lanka itself. In 1934 Tagore had said that it was time the “spiritual bond” between Sri Lanka and India was put together again. And there is a likelihood that ties with Bengal (both West Bengal and Bangladesh) will grow as a result.

Sri Lankan makes

a Bengali film

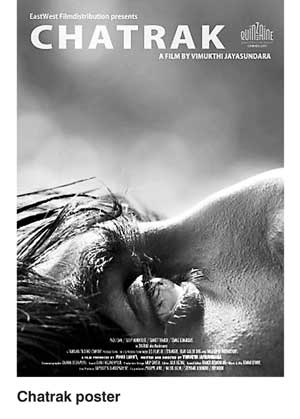

As a first step in connecting Sri Lanka with Bengal, the young Sinhalese filmmaker, Vimukthi Jayasundara, has made a feature film in the Bengali language set in Kolkata. Vimukthi’s Chatrak (Mushroom) is on the havoc that mushrooming high rise buildings are causing to the social and economic fabric of modern Kolkata.

Made in the tradition of the renowned Bengali film maker Ritwik Ghatak, Chatrak was shown in the prestigious Directors’ Fortnight at the Cannes Film Festival in 2011, and also at the Toronto, Pacific Merdian and Vladivostok international film festivals.

Within a screening time of 90 minutes, Chatrak brings out significant aspects of the realities of urban India as seen in the metropolis of Kolkata, in which corporate interests determine the pattern of growth irrespective of social consequences, and where ambitions to succeed as per the parameters of the day, tear the social fabric and create traumas.

The film shows how values promoted by the corporatisation of the economy and society lead to conflicts, isolation, remorse, disappointments, irreversible mental imbalance and even suicidal tendencies. The situation created by corporatisation leads to the creation of roles and duties which are performed mechanically and often brutally. Even so, remorse creeps to the surface on occasion because, after all, the denizens of the modern world are, at the core, human beings, not automatons.

In the story, the main facets of Kolkata’s physical and socio-economic landscape are portrayed through the lives of the successful but troubled architect, his independent minded lady love, and a deranged younger brother. Vimukthi has portrayed India in all its nuanced complexity

Drawn to Bengal

In a conversation with this writer, Vimukthi revealed how he hit upon the idea of making a film in Bengali.

“I have travelled in India extensively, and made many friends in the film world. As a student at the Film and Television Institute in Pune, I saw a lot of films and was particularly fond of Bengali film makers Satyajit Ray and Ritwik Ghatak. I got the craft of film making from Ray and my political sensibilities from Ghatak,” Vimukthi said.

Asked what attracted him to Bengal, he said: “During my visits to Kolkata, I found that the sights, sounds, the music and the people were familiar, very much like what one would encounter back home in Sri Lanka. The peoples’ sensibilities were similar too. I did not for a moment feel that I was in a foreign land.”

The idea of making a film in India came up at a meeting with his long standing Kolkata-based friend, Bappaditya Bandhopadhyay, a producer and director of Bengali films. Bappaditya said he could rope in Vinod Lahoti, a Kolkata film financier if Vimukthi wanted to make a Bengali film.

On choosing the subject and the story Vimukthi said: “I hadn’t a clue about what to portray. So, I decided to roam the streets of Kolkata day after day, observing the lives of the people in various parts of the city at various times. What struck me at that time was the mushrooming of posh high rise buildings in sharp contrast to the squalor around. I saw the sharp differences existing between the rich and the poor and how the poor were duped into parting with their agricultural land for small sums of money on the promise of jobs on the construction sites.”

From interactions with the middle classes, he learnt about their aspirations and problems. He also found that at least a section of Kolkata society was aware that people were being taken for a ride. This is brought out in a scene in the film in which an old man is trying to wake up a younger man sleeping under a bridge by telling him loudly how the British bought the three villages which became the nucleus of the imperial city of Calcutta for a mere Rs. 1,300 and that a similar thing is happening now.

If Chatrak is followed by more cross-border artistic ventures, links between Sri Lanka and Bengal (including Bangladesh) could be revived for mutual benefit.