Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Tuesday, 26 May 2015 00:01 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Ashwin Hemmathagama

Health statistics indicate that smoking leads to the death of 60 Sri Lankans on a daily basis (21,000 annually) and that the Government spends between Rs. 10 million to Rs. 15 million to treat a single cancer patient.

As former Health Minister, President Maithripala Sirisena has mentioned, approximately 40% of these cancer patients are between the ages of 30 and 40. He has further mentioned that the sale of cigarettes has declined by 12% during the past two years.

The long-drawn battle to implement the pictorial health warnings on cigarette packets has ended with tobacco manufacturers directed to implement an 80% pictorial warning in addition to text warnings on all packs containing tobacco products.

To further deter smokers, the State has been hiking the price of cigarettes year on year, and currently prices in Sri Lanka are known to be among the highest in Asia. All these efforts are with a unanimous objective of reducing smoking in Sri Lanka and eventually eradicating this health hazard from our society.

Beedi growing in popularity

But there lies a fundamental problem in winning the war. While cigarettes have taken centre stage in our offensive against tobacco, beedi – not smoked or even seen on the streets of Colombo – is growing in popularity in rural Sri Lanka, unchecked.

While there is no doubt that both cigarettes and beedi are injurious to health, why is one more accountable than the other?

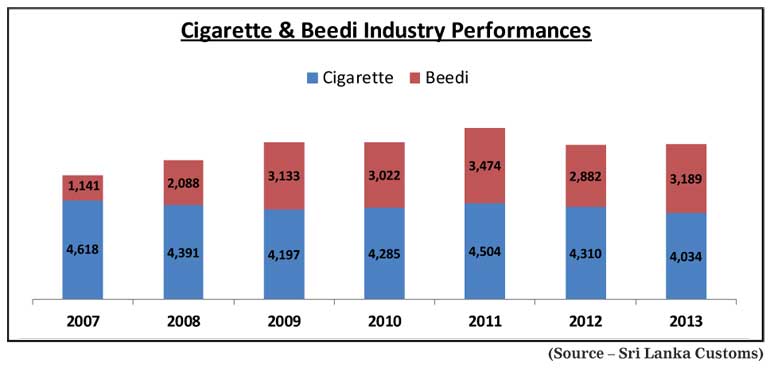

In 2014, Sri Lankans have smoked over three billion beedi sticks and approximately 3,590 million cigarettes. According to reports by Sri Lanka Customs, beedi volumes have tripled over the last seven years, increasing from 1.1 billion sticks in 2007 to three billion sticks in 2014. Interestingly, the data also depicts a 13% decline in the cigarette volumes during the same period of time.

Unlike the conspicuous cigarette industry in Sri Lanka, beedi is a small and medium scale enterprise. It engages local farmers to cultivate tobacco, imports a specific leaf called ‘tendu’ that is used to roll the beedi and of course, uses cheap labour; amply available in rural Sri Lanka.

Women in most rural households, who have lots of spare time during the day, engage in rolling beedi for a pittance using the tendu leaves imported from India. The beedi they produce is sold every few days to an intermediary, who does not have any control over accepted norms of storing and packing process.

Currently beedi is available in over 140 brand names in the market. According to industry statistics, there are over 17,000 Sri Lankans engaged in beedi-related jobs at different vertices. Beedi is a key trade item according to Sri Lanka Customs, which claims to have 800 such registrations.

Rising volumes

Beedi, which was on a decline for over a decade, has increased in volumes since 2007. Beedi volumes have increased by 180%, which has contributed to a 25% increase in the overall tobacco sector in the island despite a 13% reduction in legal cigarette volumes. All-in-all, beedi now holds 42% of the total tobacco market share in Sri Lanka. With such numbers, there is no doubt beedi is a thriving industry in the country.

The tendu leaf is the only material levied with State import tax, which accounts for less than 1% of the overall sector contribution to the State coffers. According to Sri Lanka Customs, currently beedi manufacturers pay only the import tax on tendu leaf, which is Rs. 250 per kg of leaf imported.

In comparison, the excise, taxes and levies on cigarettes added Rs. 73.6 billion to State coffers in 2014, which is an increase of more than 10 times when compared to the tax contribution of cigarettes in 1990.

Key reasons for the increase in beedi consumption could be its price, product characteristics and availability. Price of a beedi ranges between Rs. 2 and Rs. 2.50. The availability of beedi at the small village shop provides easy access regardless of the bad odour common among beedi smokers.

Analysing prices, the cheapest cigarette is Rs. 10, allowing a smoker to purchase four to five beedis, which produces a stronger ‘smoke’. It is also supported by the fact that while the price of a regulated stick of cigarette has increased 100% from 2007 to 2014 (from Rs. 14 to Rs. 28), the price of a stick of beedi during the same time period has increased only by a mere 50 cents, leaving it affordable to rural masses. So, it is widely believed that beedi is a harmless, inexpensive substitute for cigarettes, but in reality it is as lethal as a cigarette.

Global experience

According to studies in India, in 2009 Indians consumed one trillion lightly taxed beedi per year against 106 billion highly-taxed cigarettes. Global experience shows that people give up smoking when high cost and social inconvenience provide proper incentives. Around 30% of all smokers in the United States and Europe have given up the habit. But in India only 2% of beedi smokers ever give it up, because the costs and social pressures are so low.

Countries like the United States, which are seeing increased beedi consumption among teenagers, treat beedi on the same league as conventional cigarettes. They are taxed at the same rates, are required to have a tax stamp, and must carry the Surgeon General’s warning.

As a nation, our efforts to curb the smoking menace have been commendable and we are seeing results. But smokers will find alternatives to satisfy their addiction. If we ignore the silent but growing menace of beedi, there is a possibility that it will drive tobacco consumption in Sri Lanka in the future.

The battle against tobacco in Sri Lanka must continue and must be fought aggressively, but it must be done so that we in the end win the war – for this, even the silent and unchecked aspects of the industry like beedi need to be monitored, regulated and controlled. Only then will this fight be a sincere effort to place the people of Sri Lanka and their wellbeing first.