Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Saturday, 17 August 2019 00:58 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Dr. Mohamed Safiullah Munsoor and Prof. Mohammad Abu-Nimer

It is now almost four months since the tragic and horrendous attacks on Easter Sunday in Sri Lanka which penetrated the core of our beings, setting in motion a series of emotions, beyond the initial shock. Among other emotions, this incident triggered an urge to engage and prevent such acts. There is a desperate need to engage and stand up against such acts and an urgent need for those who preach Islam to understand Islam at its core.

A few verses from the Qur’an (Sura Al-Hujjuat) underlines the universal nature of Islam: “O mankind! We created you from a single (pair) of a male and a female, and made you into nations and tribes, that ye may know each other..” and “if any one slew a person…it would be as if he slew the whole people: and if any one saved a life, it would be as if he saved the life of the whole people” (Sura Al-Mai’idah). This is followed by the Prophetic1 saying that “None of you has faith until he loves for his brother/sister what he loves for himself/herself” (An-Nawwawi, 2013). Islam at its core is an inner spirituality. So, what has gone wrong? And what can we do to make a shift for cultivating spiritual harmony?

We need to establish a common understanding of the term spiritual harmony for this can mean different things for many people. In this context, spiritual harmony can be described as reflected in our diverse capacities to express solidarity, empathy, and sympathy with those who belong to different faith or non-faith groups. This space to express these elements of solidarity and understanding become our shared sacred physical and mental spaces.

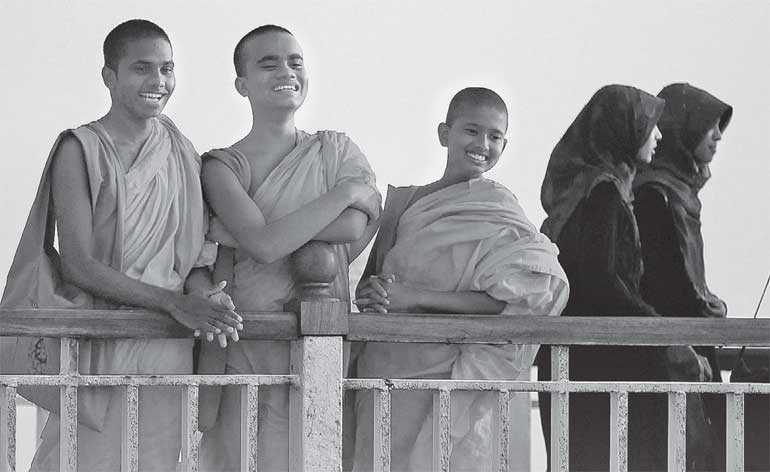

All religions have a universal set of values that we all share. Therefore the first step needed is to turn all religious narratives into its universal nature and values, which if systematically done will enrich and change mind-sets for the better and foster communal harmony. This is best done through interreligious dialogue, which has its own approach, set of methods, tools and framework, which can open pathways for deeper dialogue.

Second, there is a bigger question that lurks in our minds: ‘Can there be peace without, if there is no peace within’ oneself?, which generally seems to be brushed aside. Given that religions have tended to become institutionalised and formalistic, there is a need to concurrently focus on the outer and inner aspects, that is, while adhering to the outer rituals, which gives ‘form’ to focus on the inner dimension or the ‘spirit’, which forms the brain-heart nexus (Munsoor, 2018).

To dive deeply and enhance spirituality, religions have a plethora of contemplative practices including meditation (vippasana – introspection and anapanasathi – mindful breathing) in Buddhism, to the multifaceted yogic system in Hinduism, the centring prayers in Christianity, and dhikr (remembrance) in Islam, which is composed of silent prayers, recitation and mindful awareness (maraqaba). There is increasing neuroscientific evidence (Munsoor & Munsoor, 2016) that these above mentioned contemplative practices results in positive benefits neuro physiologically, as well as psychologically, and impacts on one’s attitude and behaviour if this is done properly, with deep internal meaning and in a sustained manner.

Thus, reminding ourselves on the need to strengthen our inner spirituality is a first step to prepare ourselves to be in spiritual harmony with our environment. Third, universal spiritual education (values, tools and rituals that facilitate deeper understanding of all religions), has been grossly lacking in all schools, as well as public and private spaces including madrassas, piriveenas, gurukals and seminaries, while one sees a recent emergence of ‘spirituality in the public sphere (Bouckaert, 2003)’ with its practices being deemed useful.

We should not be afraid to teach our children about the positive values that every faith group brings. In today’s content this seems a must in our troubled world. Fourth, within the religious space the approach, methods, tools are available and need to be used by the religious scholars and the general public in a more serious and systematic manner since it has implications both at an individual and societal level. Religious leaders are expected to model peacebuilding by reaching out to those who are affiliated with other faith groups.

A huge contribution to security and against violent extremism can take place when religious leaders genuinely assume the role of peacemakers inside and outside of their community circles. However, for this to take place our policy makers and security institutions have to reach out to such religious leaders and seek their input and support through positive engagement and not through political manipulation or/and intimidation.

“Returning hate for hate multiplies hate, adding deeper darkness to a night already devoid of stars. Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that (Martin Luther Jr., 1963). Therefore, changing the inner compass with contemplative practices, value based systems, spiritual education, and positive engagement with religious leaders and policy makers within the Sri Lankan context would enhance the healing process of post traumatic contexts and lead to greater clarity in the direction of our life’s journey. There is a need to make a conscious effort to exude the patience, love, tolerance and compassion to heal our hearts and mend our minds.

References

1Abu-Nimer, Mohammad (2018) Alternative Approaches to Transforming Violent Extremism: The Case of Islamic Peace and Interreligious Peace building., Berghof Foundation, p5; Push factors – poverty, unemployment, marginalisation, sectarianism, government oppression, lack of opportunity etc.; and Pull factors – monetary benefits, protection or safety for a person’s family, sense of belonging, revenge, personal empowerment, religious rewards etc.

Al-Qur’an, Sura Hujjurat [49:13]

Al-Qur’an Sura Al-Mai’idah (5:32)

An-Nawawwi 40 Hadiths – narrations (2013), Prophet Mohammad saying as reported by Anas In Malik and recorded in An Nawawwi, Hadith No: 13, Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī and Muslim., last retrieved 3 June 2019; https://40hadithnawawi.com/index.php/the-hadiths/hadith-13; This is called the golden rule and this is found in all religion as diverse as they are in and is a binding spiritual thread.

Bouckaert, Luk (2003), Spirituality as a Public Affair Ethical Perspectives, 10, 2, p 106

Luther Jr, Martin (1963); Famous Quoted, Martin Luther King Program, Washington State University, 2019; last retrieved 3 June 2019; https://mlk.wsu.edu/about-dr-king/famous-quotes/

Munsoor, Mohamed Safiullah (2018), A Model of Spiritual Leadership and Self-Development: A Case Study of a Spiritual Order, PhD thesis, Academy of Islam, University of Malays, Malaysia. This concept of the Brain-Heart Nexus is elaborated and a model presented of spiritual leadership and self-development. Munsoor, Mohamed Safiullah & Munsoor, Hannah Safiullah (2016), ‘The Well-Being and the Worshipper: A Scientific Perspective of Selected Practices in Islam, Humanomics, Vol 33, Issue: 2, pp.163-188, https://doi.org/10.1108/H-08-2016-0056; Several detailed references and practices relating to major religions (Buddhist, Hindu, Islam & secular practices) and their neurophysiological and psychological benefits are cited in the article.

The First People: The American Indian Legend – The Tale of Two Wolves: Cherokee Legend, last retrieved 23 May 2019; https://www.firstpeople.us/FP-Html-Legends/TwoWolves-Cherokee.html

(Dr. Mohamed Safiullah Munsoor is a Sri Lankan national who studied at Royal College, Colombo and then moved on to complete his first Ph.D. in International Rural Development with focus on Local Organisations in Myanmar (University of Reading, United Kingdom) and his second Ph.D. in Spiritual Leadership and Self Development: A Case Study of a Spiritual Order in Malaysia (University of Malaya). He is currently the Director Programmes, with the International Dialogue Centre (KAICIID), Vienna, Austria involved in Interreligious Dialogue in Peacebuilding.

Professor Abu-Nimer is a Senior Advisor at the International Dialogue Centre (KAICIID), Vienna, Austria and a Professor at the School on International Service of the American University (AU), Washington, DC. He also served as Director of the Peacebuilding and Development Institute at AU. He is the founder of Salam Institute for Peace and Justice. He has conducted interreligious dialogue and conflict resolutions workshops worldwide including in Sri Lanka. In addition to his numerous publications, he is the co-founder of the Journal of Peacebuilding and Development.)