Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Wednesday, 18 October 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The other day there was a communiqué that Sri Lanka must have a SME policy as per the direction from the leadership of the Yahapalanaya Government. It sure gave breath to the economy that is currently nose diving with a growth at 4.7% and all banks curtailing short-term lending.

The other day there was a communiqué that Sri Lanka must have a SME policy as per the direction from the leadership of the Yahapalanaya Government. It sure gave breath to the economy that is currently nose diving with a growth at 4.7% and all banks curtailing short-term lending.

This directive comes in the backdrop of the rating agency Moody’s downgrading the Sri Lankan banking sector from Stable to Negative, the core reason being property exposure where nonperforming loans are nudging from 2.7% to almost 4% in State banks.

In the backdrop of SMEs contributing to over 70% of the economy, a point to note is that doing business in Sri Lanka is getting tougher even though many expected a pro private-savvy growth agenda-driven strategy post 8 January 2015.

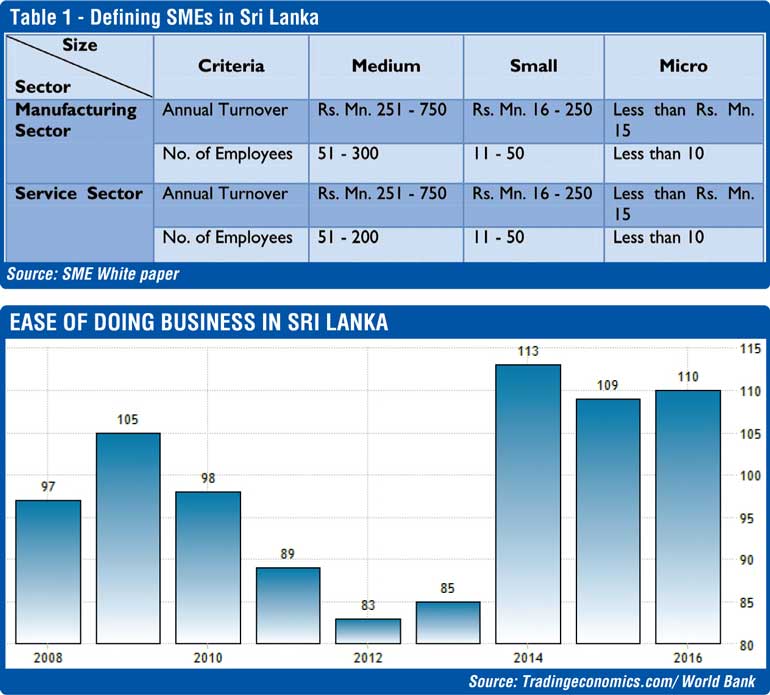

According to the World Bank’s ‘Ease of Doing Business Report for 2017,’ Sri Lanka has slipped to the 110th position from the current 109th rank even though the country has made strong progress in reforms relating to starting a business and protecting minority investors. Hence we see that whilst driving the economy to be contemporary, the country has not kept the pace of growth in relation to other countries.

Apart from the ease of doing business, on the overall brand value of the country we have not made the country attractive on exports, FDI or tourism which are strong economies internally for SMEs. The brand value as per the latest Nation Brand value computation reveals that from $ 74 billion in 2016 it has just moved up to $77 billion which is not healthy for a progressive country and the Government at play that is linking the country to the world.

If we define an SME, the sector generates more than 70% to Sri Lankan GDP in the focus sector of exports and almost 73% are small and medium enterprises. Whilst there is considerable visibility on the formal sector be it on print or electronic media, we rarely see SMEs in any of the glitzy magazines or the financial section of any of the newspapers.

If numbers are crunched a colossal $ 60 billion contribution comes from SMEs to the economy. It may not be incorrect to say that they are the forgotten entity of the Sri Lankan economy just because their share of voice cannot be heard. Hence the new policy perspective coming into play is opportune but a point to note is that we have heard this rhetoric many times in the last 15 years with a ‘SME white paper’ presented to Cabinet too some years back too. But sadly we never saw the reality hitting the market place.

The key issue in this sector is that there is no proper definition of what an SME is. This is not unique to Sri Lanka but common to many countries around the world, as classifying an SME can be on a multitude of variables that can vary from one country to another. The absence of data in this uncontrolled sector of the economy adds to the complexity.

In Sri Lanka, some say that an enterprise which has less than 99 people and an asset base of four million can be termed an SME. Then another definition is less than 50 people but an asset base of 20 million. The World Bank states that if any enterprise has less than 99 people, it can be termed an SME. Hence it is very clear that this is one key policy decision that Sri Lanka needs to take as a country given that concessionary financial facilities can be targeted as well as availability of specific business development services can also be made available if there is a clear classification of an SME.

Apart from the fact that over 70% of GDP is generated by SMEs, another important point to note is that from the 5,000 odd exporters that generate almost 11 billion dollars to the economy, nearly 80% of them are SMEs. If we take another sector like the tea industry, from the 300 million kilograms of tea that Sri Lanka produces, almost 70% of them are from the small holding producers that have just half-an-acre of land area, which once again comes under the SME classification. Hence we see that there are many unsung heroes in the SME business who never get highlighted or for that matter identified so that development can be done from a State perspective.

If I may take you back to how the SME sector evolved in Sri Lanka, apparently way back in 1952, the World Bank had suggested that the Government develop SMEs rather than promoting large industries. Then in the 1960s the  Sri Lankan Government began focusing on developing cottage industries and SMEs for the sole purpose of saving foreign exchange through import substitution and to spruce up employment.

Sri Lankan Government began focusing on developing cottage industries and SMEs for the sole purpose of saving foreign exchange through import substitution and to spruce up employment.

Thereafter in the 1977 post-liberalised economy, SMEs were developed to drive the export market, which is actually when the SME sector was unleashed to become the backbone of the country’s economy. With this development came the multitude of Government agencies and private sector banks that were being set up to provide the policy environment to support this fast-developing business sector. This included the department of small industries, CISIR, EDB, SLSI, IDB, SLECIC, Textile Department, National Gem and Jewellery Authority, NEDA, DFCC, NDB, SME Bank and later renamed as Lankaputhra and today, the powerful bank called Regional Development Bank (RDB) to name the key institutions.

In the recent past we have seen many line ministries like the Ministry for Traditional Industries and Small Enterprises coming into the fray, which explains the fast-growing importance of this sector but sadly the key issues have not been successfully addressed.

One of the key issues in Sri Lanka is that there no clear policy for a typical small and medium scale entrepreneur to be guided. In Thailand there was a SME promotional plan and in Philippines there was SME development plan launched with aggressive field administration. ASEAN got together and launched a blue print for ASEAN SMEs which got traction but Sri Lanka could not latch on to this.

The challenges that SMEs are up against are that to register property it takes almost 258 days and 5% of the land value, which is not conducive to foster entrepreneurship. The lack of business development services, in adequate research and development facilities, quality certification at district level and the linkage to export markets come up as key issues whilst the biggest issue is the difficulty in having access to concessionary finance.

Another point highlighted by the SMEs is that almost 28 types of taxes have to be paid to a bank during the year, which is very cumbersome and time-consuming and it must be a priority item that must be addressed. Some went on to say that a typical SME being stretched for talent is today faced with labour issues given the employment rate being at below 5%.

If we take a cue from a country like India, way back in year 2010 there were around 30 million SMEs in India but with key changes to policy on the lines discussed above, the progress has been phenomenal. As at today, the number stands at over 600 million SMEs as per the statement by the Minister of Small Scale Industries – Agro and Rural Sector.

The Secretary of the said Ministry went on to say that with minimum policy changes, the greatest results were being achieved, given that there was a passionate commitment to drive strategy. Whilst Sri Lanka continues to be rhetoric in its focus on SMEs, we have not been able to develop the backbone of the country to driving economic growth.

The first key task is for this sector of business to have a single line ministry. This will lead to a clear and focused agenda that can be developed which will be followed by a set of policy guidelines. If this is done, some of the key issues highlighted above will be addressed due to the focused manner of implementation.

Secondly, a SME Policy Unit must be set up so that very close contact can be made with the SMEs, which will result in an updated database which will make the task of developing specific business strategies possible. This can also lead to a once-a-month SME forum to be organised where the key obstacles that SMEs are faced with can be highlighted so that a PPP model of problem solving can be applied just like the ‘Samatha Piyasa’ Exporters Forum that was staged at one time at the EDB.

Thirdly, support linkages can be developed with ITI, EDB, SLSI and the Department of Registration so that at regional level too this service can be accessed by a typical SME. Fourthly, the issue of access to finance must be addressed. This can only be done if financial rigour is being practiced by the SMEs so that when it comes to documentation required for one to take a loan, things are in order.

Maybe the Regional Development Bank can have a unit that helps SMEs structure their documentation in a way that access to finance is possible even if the cost of the capital is not as attractive, the logic being that even if interest rates are reduced to levels that are very attractive, if financial discipline is not being practiced by an SME, access to finance will still remain an issue.

Finally, maybe we need to fast-track the setting up industrial estates in different parts of the country but in a sector specific manner, just like in India, so there is greater focus and stronger networking that leads to the industry as a whole becoming very competitive. This can also help drive specific technology that can be shared by the different competitors as well as the employment can be targeted by sector. A classic example is Atchchuveli industrial zone which could be linked to the South Indian economy.

Whilst the recent discussion of the SME policy to be launched is positive, I feel even if we can include key strategies into the 2018 Budget for activation will be more beneficial than an elaborate document targeting SMEs, the logic being that getting together a multitudes of SME agencies together can be a nightmare given the politics of Sri Lanka. Hence the Kaizen approach will be more productive.

(The author was a Board Director of the first SME Bank of Sri Lanka when he was the Chairman of Sri Lanka Export Development Board.)