Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Friday, 29 December 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Whilst the economic challenges remain in Sri Lanka stemming from exports to foreign remittances, from tourism to FDIs in the backdrop of a sluggish economy growing at 3.4%, we now move to the political battle at the village level.

Whilst the economic challenges remain in Sri Lanka stemming from exports to foreign remittances, from tourism to FDIs in the backdrop of a sluggish economy growing at 3.4%, we now move to the political battle at the village level.

On 10 February, 15.8 million Sri Lankan’s are expected to vote to elect 8,293 members into the 341 local authorities. This will consist of 24 MCs, 41 UCs and 276 DCs.

The 2018 elections will be unique as it will be the first time where a unique system will be in play in the country; 60% will be elected using the First Past-the-Post methodology whilst the remaining 40% will on the Proportionate Representative methodology.

If I do a deep dive the First Past-the-Post voting method is where the voter indicates a candidate on the ballot paper. The person with the highest votes wins. Almost one-third of countries globally use this system, including Canada, India, Pakistan, the UK and USA, hence it is a tried and tested practice in a democratic country.

The balance 40% get elected in the PR system. This characterises an electoral system reflecting proportionately in the elected body. A key point to note is that 25% female representation being mandatory, that became a contagious issue at nominating times.

0.8m affected by poverty

Even though 2016 data state that poverty is at 4.1% which is 0.8 million people that is actually affected, poverty in Sri Lanka has become a multidimensional situation where the low income people are faced with a situation where there is increasing pressure on the purse for one’s basic consumer needs to be satisfied.

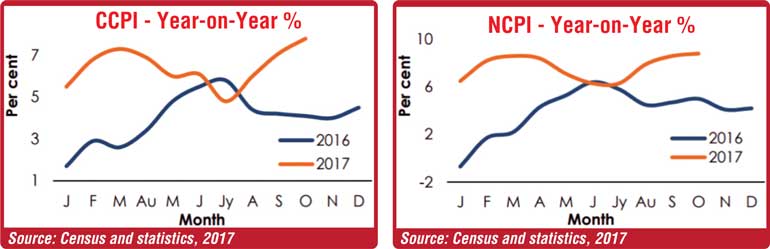

This situation is key to the health of the political debate given that overall NCPI (National Consumer Price Index) headline year-on-year change is 8.8% whilst on average the number is at 4% which means that a small shift in this indicator will take the overall poverty level to double digit. The logic being that the scatter of the poverty belt is at a very close level to the tipping point. This is the reality in Sri Lanka.

If one carefully analyses the data, the poor are faced with gaps in access to quality education, healthcare, water and sanitation, which prevents an individual from moving up the socioeconomic ladder and results in lower drive for personal development, which in turn contributes to the vicious cycle of poverty in the country.

World Bank poverty and equity data released indicated that the poverty headcount ratio, which is the percentage of the population earning below $ 1.25 a day (PPP) in Sri Lanka, declined from 14% in 2002 to 7% in 2007 and in 2016 it stands at a commanding 4.1%. Elsewhere in the South Asian region, 43.3% in Bangladesh in 2010 earned below $ 1.25 per day, while Pakistan recorded 21% in 2008. In Nepal 24.8% of the population earned less than $ 1.25.

The 4.1% means that the number of people affected by poverty is 0.8 million Sri Lankans on the 15.8 million that will vote on 10 February 2018. The World Bank reiterates that the non-poor are closely clustered just above the poverty line, which means that the number of poor is subject to sharp increases when there are slight changes in economic conditions which is what the Government is trying to avoid by introducing a maximum retail price for 13 items in the basket of food. The issue is that unless the supply chain is examined, these price controls will remain just academic in nature.

If we do a deep dive we will also see that in the rural and urban sectors, the headcount ratios are way above for the former, which means that poverty is essentially a rural phenomenon. This is why the power of the village comes into focus. This is the essence of the political discussion today given the 10 February 2018 elections.

In the strategy of driving growth through the village, the agricultural sector will play a major role. If we analyse the numbers in the agricultural sector, GDP has fallen while the workforce employed has remained more or less the same. Hence, one can argue that a higher level of agricultural output can drive down the poverty level like what we experienced some years back where due to the favourable weather condition we had positive production in tea, coconut, paddy and rubber.

However, poverty does not seem to be inversely related to the growth in overall GDP. This throws out some interesting implications. Merely attempting to raise agricultural subsidies may not raise the per capita incomes of farmers unless accompanied by measures to reduce the workforce engaged in basic business practices like efficient logistics, better warehousing, and value addition strategies like attractive packaging and branding.

From the above it is evident that any cash grants given for political reasons in the near future will not help a typical villager move out poverty. A strategic initiative must be sketched out to identify opportunities for the poor to participate in economic activity through skill enhancement at the village level. This includes building irrigation projects, causeways and village level warehouses. Provide concessionary funding and technical knowhow by mobilising resources from donor agencies that include promotional support for marketing the produce to indirect exporters to name a few.

China adopted a unique strategy in 1979. A so-called Village and Town Enterprise (VTE) program was launched. This was essentially a small and medium scale enterprise initiative. The learning to the world that was conceptualised was that one does not have bring the village to the town and drive manufacturing up or hand out subsidies to drive development

A more strategic growth was embarked on by way of taking manufacturing to the villages and agricultural sectors. The phenomenal growth of the Chinese economy was based mainly on the growth of the VTEs. May be Sri Lanka can do the same on the sound footing. After all, who ever thought that a villager from Pannala would become the world’s best maker of lingerie?

A lesson in time as highlighted above is that merely raising budgetary allocations to the agricultural sector is not going to reduce poverty levels. The village level developmental must be covered with a Rural Development Act. This can lead to a drive of extending rural credit to rural non-agricultural occupations. The Bangladeshi Nobel award winning work of the Grameen Bank is a case in point. Maybe the private sector can do the same on a micro basis.

Another best practice I can remember when I worked in India was when Hindustan Lever developed a program on the theme ‘Shakthi Amma,’ which helped the rural area become an integral part of the growth model of the company.

Given the above background, we see that if the 2018 elections are to make a difference at the village level, one will have to convince the voter with strategic initiatives and not with short-term injection of cash.

Given the debt payments touching $ 3 billion yearly for the next three years, strategic investments at village level will be a tough agenda to follow. The million dollar question is, how will a typical village react at the 10 February 2018 elections?

[The writer is a former Chairman of the Sri Lanka Export Development Board, Sri Lanka Tourism and National Council for Economic Development (NCED). He was also the Commissioner General for Sri Lanka at World Expo 2015. Currently he is CEO of an international property company based in Sri Lanka.]