Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday, 20 November 2017 03:42 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

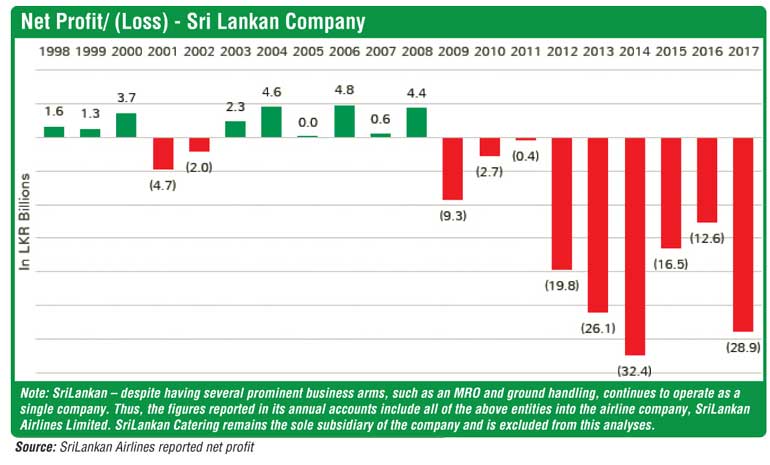

airlinerealist.com: SriLankan Airlines – the national airline of Sri Lanka – has been in the news lately, mostly for the wrong reasons. And the criticism is justified. SriLankan last made a profit in FY2008 and has been unprofitable since. That was also the last year of a strategic relationship between Emirates and SriLankan – before it was scrapped by the former President of Sri Lanka in a much publicised incident. Hence, critics are quick to point out that there is certainly something wrong with the way the airline is run – for Emirates made money during all the years and SriLankan on its own has continuously failed to do so.

The Emirates profits

Emirates won a bid to manage the island nation’s national carrier – known as Air Lanka – in 1998. Subsequently Emirates infused a modern branding into the ageing carrier, renaming it as SriLankan, and updated its fleet with modern Airbus A330 aircraft. With the stake purchase, Emirates received management rights for 10 years (the agreement which was not renewed). It subsequently sold off its stake in the carrier for $ 53 million, at a loss of nearly $ 20 million. Let’s take a look at the profitability during the Emirates managed era.

Demystifying the results

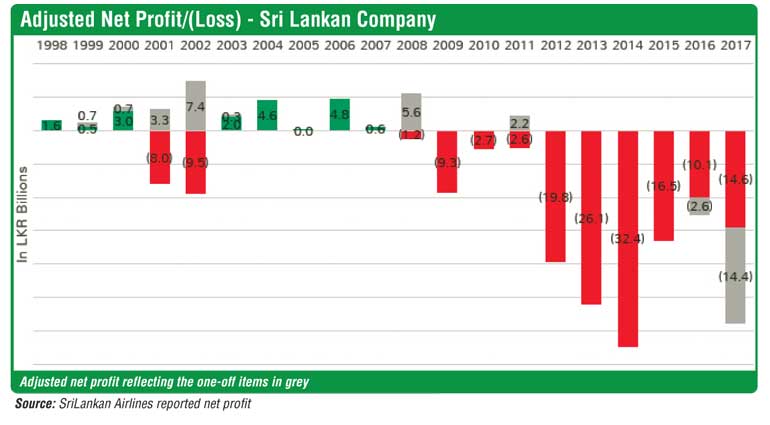

A closer examination of the results reveals some creative accounting (legitimate by all means) and that, SriLankan as a company, did not make real money in many of the years under Emirates’ control.

In several of the years, the profits were made possible through gains recorded by selling and leasing back of owned aircraft as well as the disposal of other assets. These include;

In 2016 and 2017, SriLankan’s losses were impacted by the costs in relation to the much publicised cancellation of its Airbus A350 lease agreements.

If we were to adjust SriLankan’s performance for these one-off items, the airline’s real profitability during the period looks quite different.

SriLankan appears to have made a change to its heavy maintenance accounting policy in FY2014 to account for the cost of heavy checks under accrual basis (Page 24, Annual Report, FY2014). This change has been restated for the immediate prior year but not for the earlier years. As such, the results for the prior years are reported without this cost.

If the majority of the fleet were all due for heavy maintenance in later years (which is in line with fleet age and was a likely reason for the earlier policy), this could imply a significant charge of LKR2-3 billion per annum for the prior years if restated. Such a change would make a further dent in the profits recorded during the Emirates era, as the maintenance cost was legitimately understated.

The transition

A marked deterioration in the airline’s performance begins in the FY2009 (SriLankan’s financial year runs from April to March, with 2009 referring to the 2008/09 year ending in March 2009). This took place as SriLankan faced a rapid rise in fuel price, that drew many profitable airlines into losses. Hitting the company hard were a Rs. 1 billion loss on fuel hedging (reversing a Rs. 1 billion gain in prior year) and a Rs. 0.5 billion loss on exchange (reversing a Rs. 0.6 billion gain in prior year). Its leasing costs had risen only marginally over the prior year, however this was despite the company returning two aircraft to lessors during the year and operating less flights – resulting in an overall higher lease cost per hour as three A340s had been sold and leased back during the last year under Emirates control. The company had sought to drive down its costs, reducing its staff cost by 9% and advertising cost by 63%. Unfortunately the detail that can be gleaned through annual reports is limited as the airline continued to use the accounting format inherited from the Emirates’ era – which reports information in such a way that limits showing details of what impacted the operating profitability.

During the year, the company recorded a net loss of Rs. 9.3 billion – causing the same amount to be wiped off its accumulated profits – which was just Rs. 9.3 billion when Emirates management contract ended. Against this reduction in equity, the company’s net assets diminished by a further Rs. 7 billion as it withdrew a fixed deposit – likely for funding requirements. The company has since not been able to recover from this downward spiral, with the company being in a significant negative net worth at the end of FY2017.

Fuel price impact

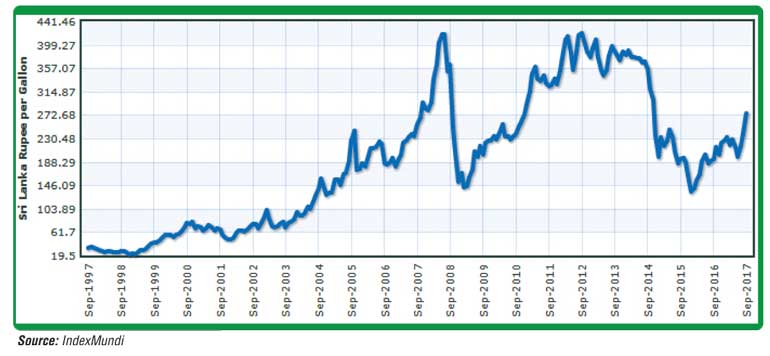

Looking at the jet fuel price in LKR terms shows that it has been full of volatility. This is driven by the fuel price spikes seen during 2007-2009 and 2012-2014 and made worse by a rapid depreciation of the LKR against the USD during recent years.

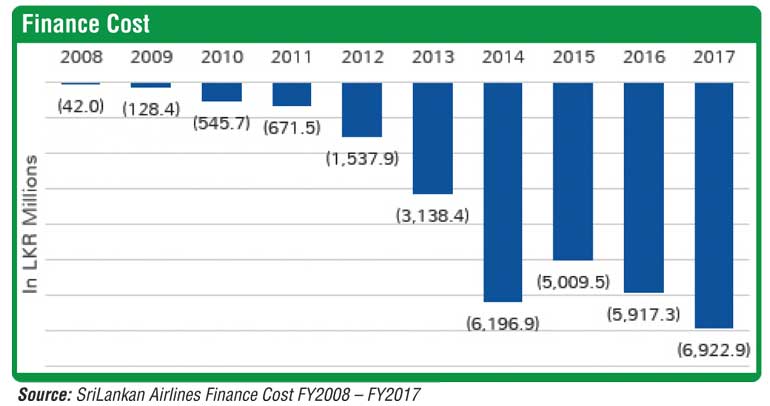

Finance cost

The airline has seen an alarming rise in its finance cost, as the company kept losing money and had to rely on short term funding facilities with high interest rates. As the company’s annual reports indicate, the 2015-elected government in Sri Lanka stopped making equity infusions into the carrier and had instead directed the carrier to obtain loans from state banks to meet its funding gaps. This had significantly ballooned up the airline’s finance cost, as shown below.

Ancillary businesses – a rising star?

Amidst all these, the revenue growth of the airline’s ancillary businesses has been very encouraging. Its Air Terminal Services (supposedly referring to ground handling) revenue increased from Rs. 11.5 billion in 2016 to Rs. 16.7 billion in 2017. The Catering unit too recorded a modest increase.

The growth in Air Terminal Services revenue is particularly astonishing, with a revenue of only LKR3.4 billion in the year which Emirates departed (FY2008) and a revenue of Rs. 1.4 billion in the last year of Air Lanka branded operation (FY1998). It is our view that the company should consider branching out these units as standalone operations, which would provide greater opportunities for growth and potentially expanding to nearby regional airports. Such an expansion should also provide a boost in profitability for the overall group.

Fleet mix

SriLankan has been in the limelight for its recent cancellation of leases for 4 x A350 aircraft. Paying over $ 100 m to not accept aircraft is somewhat unheard in the industry – yet no airline that is still operating has also been able to escape accepting the aircraft it committed onto.

However, a factor worth noting is that – following the sale and leaseback of its owned fleet over the years – SriLankan now operates a wholly operating leased fleet. While having an all leased fleet is not uncommon for a smaller start-up carrier, a successful near billion dollar airline having an all leased fleet is relatively unheard of. This is owing to the liabilities that the operating leases bring in and the significant recurrent cash payouts that are involved – for aircraft rentals as well as maintenance reserves. It may be worth for the airline to evaluate the potential of obtaining used narrow-bodied aircraft on a financial lease or to look at the possibility of buying out the leases on some its older narrow-bodies as a means to lower its aircraft lease cost liability. This would not require a significant upfront investment and presents a safer bet in terms of residual value risk than purchasing a costly Airbus A330.

Route network

Whilst it has been argued by some analysts that the launch of its new Melbourne service presents a distraction – we would disagree with this view. Sri Lanka is a market that is known for a low yield – and it is quite difficult to envisage a long haul route to Sri Lanka becoming profitable from the set-go. Yet, not operating such a route does not provide the airline any benefits as its fixed cost base is unlikely to dwindle.

Whilst it may not be immediately evident from an economics point of view (something that we advise our clients frequently) – the deployment of the same aircraft on a shorter set of routes does not necessarily derive a major financial benefit (if at all only in route profitability), as the same costs need to be spread out over less seat kilometres. Whilst the airline may receive a higher yield on shorter routes, it will have to do so at the cost of a lower utilisation and operate a lesser number of seats owing to market size limitations. In the end, the sum of parts may be lesser than the whole. This is very applicable in a case like SriLankan, where the carrier seems to be unable to get out of some wide-body lease commitments.

A marquee route such as Melbourne, provides the airline a better visibility on the global scale and boosts its brand awareness. It makes the passengers stop and take another look at SriLankan as a viable option. It also positions the carrier as a formidable competitor to its stronger rivals, following years of retrenchment. Such a boost would be much-needed to push the carrier out of its current slump.

However, some of the other recent network decisions by the airline are questionable. It has recently initiated direct flights to Gan Island in Maldives. While this route provides the carrier with a unique positioning as the only foreign airline to serve two points in Maldives, the demand for such a service may be arguably limited. The same could be said of the airline’s new services to Coimbatore and Visakhapatnam in India, from where there is limited demand into Sri Lanka. It may serve best in the airline’s interest in short-term if those aircraft time were utilised on a route where the revenues are guaranteed and no deep discounting is necessary.

It has also launched direct services to Hong Kong, after over 30 years of serving the city via Bangkok. However, in doing so, the carrier has switched its services to a narrow-body equipment. It certainly is a risk-averse strategy and may pay-off, but as evident by the recent upgauging of Cathay Pacific services to Colombo – this means the airline is foregoing a large cargo potential.

Meeting challenges in the DNA

It should however be noted that Emirates had control of SriLankan during a much more challenging era. Sri Lanka was a less safer place than it is now, owing to terrorist threats. The airline nearly lost half of its fleet at one point (though it had a surplus on the termination of leases for destroyed aircraft – likely from insurance receipts). It had to face a major decline in demand with the Boxing Day Tsunami that also impacted Sri Lanka. The dawn of peace has made the island a much more attractive tourist hotspot, although that has also meant more competition has been attracted. Nevertheless, the carrier is fondly known in the aviation circles for the spirit with which it has withstood the challenges that it faced – and if the will is there, it will only be a matter of time for the carrier to emerge from its present-day problems. But how does one get there?

A change in strategy the way forward?

The above analysis reveals a startling fact, that the SriLankan business model has been unviable since the spike in fuel prices – irrespective of the owner or management – and a sustained transformation of the model has not taken place to prepare the business for a high fuel price environment. Granted, the business has faced many challenges. However an apparent lack of direction – and dare we suspect – a lack of will from a state shareholder as usual, has seen the company take only evolutionary steps where a revolution may be required. This is substantiated by the fact that the airline has not made a profit ever since jet fuel rose above the Rs. 150/gallon level. In a hypothetical world, had Emirates been in charge, it is very likely that they would have conducted a major change in business direction or been forced to sell off its stake.

SriLankan has done several things right, such as the introduction of a modern business class as well as the addition of several new fuel-efficient narrowbodies (it recently became the first Asian operator of A321neo). It also offers a very good in-flight connectivity with Wi-Fi, far ahead of some leading airlines. However, the airline may need to act fast and act decisively if it is to make use of its new-found optimism with the Melbourne route launch.

Such a reset of the business model could require the carrier to reconsider its present business model, with a potential move to a denser operation and sweating its assets harder. The Asian region is set to witness a great expansion in travel demand and SriLankan is set to reap the benefits with its close proximity to India, one of the fastest growing travel markets. Coupled with Sri Lanka’s potential as a tourism hotspot, SriLankan could derive a significant traffic stimulation with the right tactics.

Market data reveals that SriLankan has a relatively low Revenue per ASK compared to leading names in the industry. However, its gap in Cost per ASK against the peers has narrowed over the years. SriLankan is known to be one of the most generous airlines in terms of on-board service. While this has attracted it a lot of praise and passengers – in the current status of being faced with a crisis, they might need to consider a shift in this strategy.

The most apparent options are either to drive an improvement in its yield, by exploiting the high load factor it enjoys – or to densify its Economy cabin by unbundling some of its services. Doing away with some of the ‘generous’ baggage allowances as well as lowering costs through reducing the ratio of Flight Attendants per passenger may be a good starting point. On the front of the cabin, for which it has already invested heavily – and has an industry-leading product, the airline needs to rebuild its brand image strongly and to gain more prominence among the business traveller.

While this strategy of a leaner operation at the back of the plane and extravagance at the front may appear at-odds at first glance, it has seen successful implementation at several carriers – with two of the most prominent being Emirates and Air New Zealand, where the cabin product is relatively dense but the brand experience sells. Air New Zealand as well as Aer Lingus are two service strategies which SriLankan could mimic with relative ease to suit its target markets.

The carrier would also need to seek to bring down its cost base – which would require dialogue and buy-in of the unions. It is understandable that any government would not want revolutionary cost reductions to take place – for such actions, originating from a state owned corporation, could hurt the Government’s popularity. Sri Lanka’s Government over the past year has been committed to finding a partner to overtake SriLankan yet again. The process garnered interest from several big names, including TPG Capital – which pulled out in the end.

However, from our point of view, introduction of a partner is unlikely to bring in many benefits to an airline in the situation of SriLankan – other than if the shareholder is strictly intended to rid itself of the funding commitment. Any airline investor – potentially one that is coming from the region or the Middle East – would seek to clip SriLankan’s wings, as its recent expansion would certainly become a threat to them if not ‘derailed’ soon enough. Such a step can also be justified easily by way a business plan, for a route with a longer stage length would always result in greater losses for obvious reasons. However, it necessarily will not bring any strategic benefit to the long term future of a carrier. Any investor would need to conduct a substantial re-engineering of the business model and internal processes to turn the carrier’s fortunes. This could also require some difficult decisions, such as salary reductions or lay-offs. In this case, there would be no discernible difference to the employees or the country irrespective of whether such a process is conducted by an outside investor or a home-grown management. In fact allowing a home-grown team to conduct this process could certainly serve best in the island nation’s long term interests – for there is a great prospect to turn the carrier into a regionally strong player, IF the state can fund that exercise for a couple of years. However, funding is one key factor that the emerald isle has been short of – for which in recent times it has been forced to sell-off the majority of its new built infrastructure. In this aspect, SriLankan’s future will be one which with interest the industry observers look into over coming months.

(Source: https://airlinerealist.com/srilankan-performance/)