Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Monday, 4 July 2016 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Container ship MV Maersk Mc-Kinney Moller is led by pilot ships as it makes its maiden port of call at a PSA International port terminal in Singapore 27 September 2013 – REUTERS File Photo

Reuters: Denmark’s Maersk Line is fighting to remain the world’s no.1 container shipping carrier as a wave of mergers and acquisitions, particularly in Asia, creates new challengers trying to grab a bigger share of a depressed market.

Maersk itself hasn’t made a major acquisition for more than a decade but says it might be open to “the right opportunity”, although doubters believe such deals risk accumulating ships without securing enough customers.

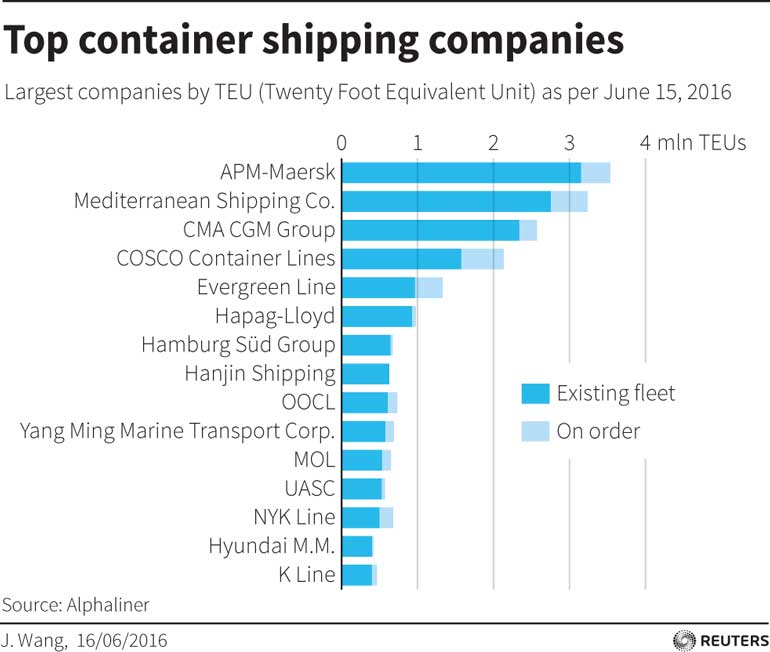

A unit of oil and shipping group A.P. Moller-Maersk, the line has a 15% share of the overall container market. However, it faces Chinese rivals with global ambitions as well as more traditional Western competitors which are buying up assets in Asia.

The battle is over the world container trade, and especially between Asian ports - one of the few relatively bright spots for an industry suffering its worst downturn since its origins in the 1950s and 1960s.

“It’s really tough and everybody in the industry is really suffering, and so have we,” Jakob Stausholm, a member of Maersk Line’s management board, told Reuters.

“We are defending our leadership position. If we are strong, there is no reason for us not to grow,” said Stausholm, who is the line’s chief strategy and transformation officer.

The container industry, which ships largely consumer goods ranging from iPhones to designer dresses, has been forced to cut costs and try to build scale due to a weak global economy and overcapacity.

“World GDP growth is struggling ... Combined with trade growth slowing down, this is a recipe for a very bad market,” said Evangelos Chatzis, chief financial officer with independent Greek container group Danaos.

In November, Maersk said it would save $ 250 million in the coming two years and reduce its workforce by 17% or 4,000 people, mainly through attrition.

It managed to post a profit of $ 37 million in the first quarter of 2016, compared with a $ 182 million loss in the last quarter of last year. However, the profit was down 95% from the $ 714 million it made a year earlier.

Competing with the big boys

Now it must deal with stiffer competition created by the mergers and acquisitions.

The world’s no. 3 player, CMA CGM of France, is in the process of acquiring Singapore’s Neptune Orient Lines for S$ 3.4 billion ($ 2.5 billion). CMA has announced it would also form a joint venture with PSA Singapore Terminals to operate container berths.

In China, former state-controlled rivals COSCO and China Shipping Group have merged to create China COSCO Shipping Corporation. Separately, China Merchants Group is buying logistics group Sinotrans & CSC Holdings Co.

“Developments are moving rapidly in Asia and the NOL deal and separate consolidation in China will give Maersk a run for their money,” a shipping industry source said. “There is a question over whether China will increasingly use these bigger Chinese lines to ship goods now over Western carriers.”

Outside the region, Germany’s Hapag-Lloyd is discussing a merger with Middle East container group United Arab Shipping Company.

Size matters in the current hard times. “If you are small you cannot survive,” said David Cheng of the Hong Kong Maritime and Port Board. “The big container liners in Asia are not regional liners - they are global liners ... They are competing with the big boys like ... Maersk, CMA CGM.”

That struggle is set to centre on Asia. “The intra-Asia trade has remained comparatively profitable despite the problems with the wider trade. Going forward, players will increasingly compete for market share on this route and there is already positioning,” a banker who arranges ship financing said.

“The CMA CGM acquisition of NOL is a case in point of that type of positioning.”

Maersk Line’s parent has cash reserves of about $ 12 billion and is under some pressure from shareholders to put it to use. Chief executive Nils Smedegaard Andersen said last month that the group held “plenty of liquidity reserves for unexpected and expected investments”.

The line last made a major acquisition in 2005 when it bought P&O Nedlloyd, about five years after buying Sealand and Safmarine.

Stausholm held open the possibility of new deals. “If the right opportunity is there we will look into it,” he said. “If you look at the history of Maersk Line, we have achieved our leadership position by combination of organic growth and acquisitions.”

However, he rejected any suggestion that Chinese customers would turn predominantly to Chinese shippers. “They also need a carrier like Maersk Line,” he said. “We have a strong position out of China, particularly into Europe.”

He also pointed to Maersk’s Singapore unit. “The intra-Asia trade is small vessels and short distances and I think we compete with our MCC subsidiary pretty well in that business.”

Buying a pile of steel

Some investors doubt the wisdom of the current dealmaking.

“By taking part in the consolidation, you effectively buy a pile of steel, but customers are not loyal in this business. So the big risk is that you are left with extra shipping capacity, while price-sensitive customers slip away,” said Otto Friedrichsen, equity strategist at Danish asset manager Formuepleje. “I don’t think acquisitions is the way to go.”

Formuepleje, with around 45 billion Danish crowns ($ 6.9 billion) allocated in bonds and equities, has shunned the shipping industry. “We see major challenges for the industry in setting the market price at the moment, and that is one of the reasons we’re not investing in Maersk,” said Friedrichsen.

Analysts Rahul Kapoor and Nilesh Tiwary at Drewry Financial Research Services said the structural change would be negative for A.P. Moller-Maersk’s earnings.

“The traditional container shipping model seems broken,” they wrote in a note this month, maintaining the “unattractive” rating for the group’s stock which they first gave in April.

Bet on mega-ships

The weak market has hit the big lines which have invested heavily in “mega-ships”, largely to operate the main Asia to Europe trade route. Industry sources have questioned whether there is enough work for the biggest container vessels on the high seas at the moment, putting more pressure on profits.

“The overcapacity is too large and the recovery will take its time,” said Hermann Klein, chief operating officer with the Offen Group shipping company.

In 2011, Maersk became the first line to place orders - worth billions of dollars - for mega-ships also known as “Triple-Es”, with a capacity of over 18,000 TEUs (20-foot equivalent container units). Maersk said it had improved cost efficiencies in the first quarter of this year.

But the banker said the search for efficiency had brought its own problems. “This trade has seen a significant cash drain. So there is no surprise there are mergers taking place,” the banker said.

On top of the mergers and acquisitions, the industry is also looking to vessel sharing. Maersk was first to announce such an arrangement with the world’s number 2 line MSC of Switzerland, which started in early 2015.

Maersk said its mega-ships and the MSC alliance gave it scale and helped to cut costs. “The Triple-Es we have received have served us well. We probably expected demand growth to have been higher, but it still works well for us with the volumes we are experiencing,” Stausholm said.