Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Tuesday, 27 February 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By: Piyumani Ranasinghe

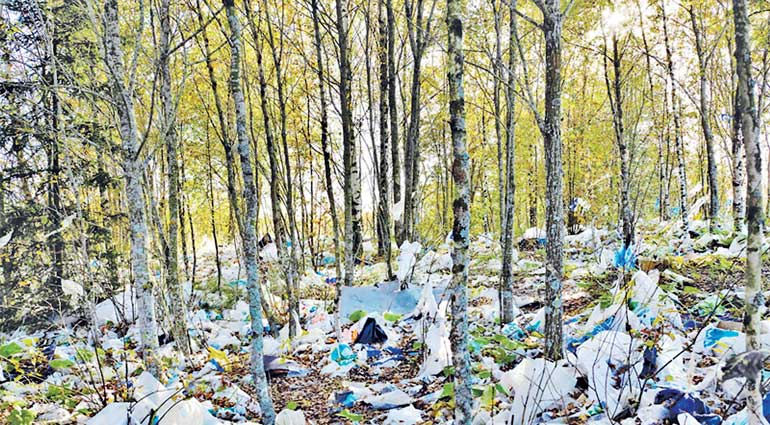

The ban on polythene that is equal to or less than 20 microns, in September 2017, was a point of debate, of course, at the time it was implemented by the Government. Besides the question of its efficacious enforcement, one can contemplate as to whether it has at least managed to reach the territories of the contemporary socio-political debates, given that the parley now surrounds the more interesting events, such as the local Government elections and of course the squabble over the changing political undercurrents. However, the current polythene legislation is not completely new to the paradise island. In fact its half-hearted predecessor, which was an order made in 2006 by the then Minister of Environment, and now President, Maithripala Sirisena, under the National Environmental Act of 1980, banned the manufacture of polythene or any polythene product of 20 microns or below in thickness. Having to legislate a similar ban a decade later, underpins the impotency of the 2006 legislation; pinpointing at the fundamental problem that lies today, in mastering the means and methods of successfully implementing a polythene ban, so that it does not meet the predicament of its predecessor. Polythene, once used for an average of 10 to 12 minutes, accumulates in landfills, oceans and waterways for a thousand years. Today, the use of polythene has become a hard practice to give up, as it is for irresponsibly dumped polythene to degrade. Successful enforcement of the legislation may even prove to be harder, if the polythene laws continue to entangle in the web of the Sri Lankan political game, fluctuating as do election promises and inoperative policies transposing along regimes.

Discrepancies in legislating prohibition

The ban in September covered a wide array of polythene and plastic products ranging from plastic decorations, polythene lunch sheets and cooked food packaging to all polythene equal and less than 20 microns in thickness. It even went on to prohibit the open burning of refuse or other combustible matters inclusive of plastics. Upon the issuance of this ban, the plastic manufacturers recoiled on the inadequate notice of implementation, which resulted in a Cabinet appointed committee to look into the ban and make recommendations before January this year. Accordingly, the ban came into full force from 1 January.

Almost a month into the ban, it is evident that for the polythene ban to work, there are many other pieces of the puzzle that should fall into place. After all, prohibition is often easy to legislate; although enforcement and temperance are not necessarily as smooth. The term ‘temperance’ is employed here to understand the use of polythene as a part of human psychology in ascribing the quotidian use of polythene as a human necessity. According to the Environmental Foundation Limited (EFL), 15 million plastic shopping bags alone are added to the environment daily in Sri Lanka; and thus, temperance undoubtedly becomes a road block, which requires the mediation of the administrative authorities, particularly by the consistent enforcement of the law. EFL notes that, in countries like Bangladesh, masses have resorted to polythene with the decline of raids and fines, which has made the 2002 ban on polythene inefficacious. Thus, consistency in enforcement is at the crux of affixing all pieces of the puzzle together.

Missing important pieces of the puzzle?

The moment the ban on polythene is brought into forefront today, it attracts public stigma against the impotency of the current Government to successfully implement a polythene ban. Yet, it should be reiterated that imposing a polythene ban takes a lot of work, especially in line with the analogy of ‘affixing all the pieces of the puzzle together’. Polythene industrialists proclaimed last week that the Government has failed to grant the promised concessions to the importation of raw materials and manufacturing costs of high density polythene. In addition, there are also persisting issues in terms of discarding polythene due to the lack of a system that enables responsible disposal of polythene waste. Hence, the fundamental difficulty is whether the Government has missed the important bits and pieces of a successful enforcement plan. Starting from the inadequate time of notice given to the ban; to the unresponsiveness in addressing the constraints faced by masses within the transition period; and the inadequate means of educating the public has led to this presumption.

Importantly, the enforcement of the polythene ban requires an inter-agency collaboration moving beyond the reach of the Central Environmental Authority (CEA): inter-linking Government agencies as well as Government and private agencies from the beginning. For example, even the transition to alternatives such as the use of glass bottles at a micro level in each agency does go a long way. EFL highlighted the importance of collaboration with Public Health Inspectors and the police in eliminating the unceasing use of lunch sheets by a number of eateries. Further, there has been debate over the resort to eco-friendly food coverings such as banana leaves, which has been the traditional Sri Lankan food cover preceding the era of polythene. However, the banana cultivation industry in Sri Lanka itself is not thriving enough to subsist such an alternative. The administration intervention in uplifting such eco-friendly alternatives is crucial in reviving the traditional environmental friendly practices amongst the population.

Public education plays a pivotal role in this regard, especially in terms of advocating that the use of polythene is a negative externality in the long run, from school children to the rest of the population. Unfortunately, the lack of apathy for recycling waste has now become a dangerous problem to the entire Sri Lankan population, although only a few eyes have opened after the Meethotamulla tragedy last year. With only 40% of plastic waste is being recycled, the Government still lacks recycling facilities.

The role of governments made of men and women

Alas, it should be understood that laws are system sensitive. According to Garett Hardin (1969)1, since the God-made laws are poorly suited to govern a complex, crowded and changeable world, the epicyclical solution is augmenting statutory law with administrative law. The administrative body thus, is responsible in the enforcement, evaluation and punishment of deviance within the total system; which renders them singularly liable to corruption, inconsistency and inefficiency primarily because governments are made of men and women, and not laws. Hence, much of the current ban, irrespective of the number of recommendations one can make, lies in the practical aspect of agency-based legal enforcement of the ban. System sensitivity of the law demands the focus of these agencies in tackling the consumer patterns regarding usage of polythene and public education. As noted by Taylor and Villas-Boas (2015)2 the sustainable compliance in a plastic ban involves two-fold behavioural changes: firstly, giving up plastic bags and; secondly, adoption of reusable bags. Given the mind-set of Sri Lankans using a polythene bag for an average of 10 to 12 minutes; the importation of plastic resins increases with the current ban since the HDPE bag requires more resins, resulting in a completely adverse situation. Hence, the sustainability of the polythene ban itself, cardinally relies upon the inculcation of the notions of reducing, reusing and recycling polythene in all policy frameworks, besides singularly ingraining them in the heads of all consumers.

(Endnotes)

I Hardin, Garett. “The Tragedy of the Commons.” Science, New Series, Vol. 162, No. 3859 (Dec. 13, 1968), pp. 1243-1248, http://pages.mtu.edu/~asmayer/rural_sustain/governance/Hardin%201968.pdf. Accessed 20 February 2018.

IITaylor, Rebecca. . Villas-Boas, Sofia s “Bans vs. Fees: Disposable Carryout Bag Policies and Bag Usage.” Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, Volume 38, Issue 2, 1 June 2016, Pages 351–372, https://doi.org/10.1093/aepp/ppv025. Accessed 20 February 2018.