Wednesday Feb 11, 2026

Wednesday Feb 11, 2026

Monday, 7 September 2015 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

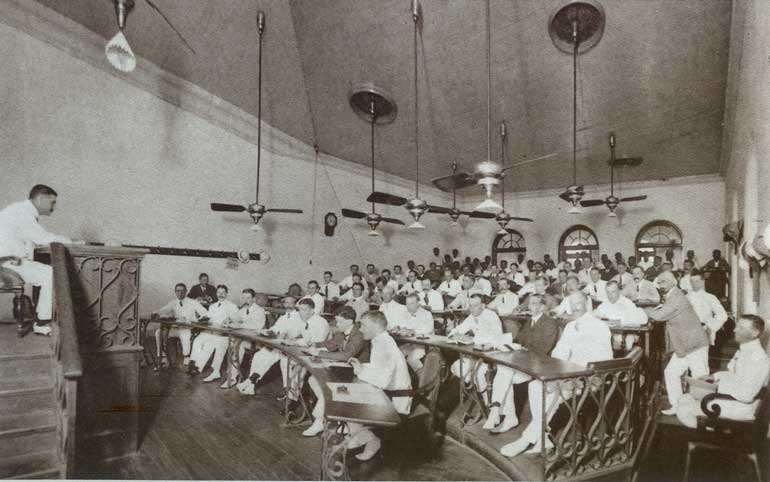

Colombo Tea Auction in its fledgling days

Colombo Tea Auction in its fledgling days

Kushani Daluwatte – Pic by Shehan Gunasekera

By Uditha Jayasinghe

The gavel cracks as the auctioneer makes a sale and the flurry of almost unintelligible words whiz on; “this is the best lot, please put in bids,” she says and the buyers do, so subtly an observer misses most of the gestures in the unassuming flow of time that has kept the 132-year-old Colombo Tea Auction the oldest operational, most expensive and largest single-origin tea mart in the world.

Every Tuesday and Wednesday as many as 140 buyers sit in three rooms of the Ceylon Chamber of Commerce, a venerable 176-year institution that has housed the Colombo tea auction since colonial times. Visitors have to obtain a special pass after making a small payment for the privilege of sitting in on proceedings that have remained largely unchanged for over a 100 years.

No photographs or recording are allowed. Business is transacted on the strength of a word. From the moment the gavel cracks, a contract has been made and will be honoured by the tea broker and the buyer within a week. No written deals, no lawyers. Tea remains a gentleman’s trade in Sri Lanka.

Kushani Daluwatte, longest-serving woman auctioneer

Kushani Daluwatte is the longest-serving woman auctioneer employed as a manager with the oldest broker, John Keells Holdings, which opened its doors in 1870. For 16 years she has sold different catalogues where each type of tea is divided into “lots” and five lots have to be sold every minute when she sits at an elevated podium with mostly male buyers fanned out high above her.

Microphones are banned. Two deputies sit on either side, helping to catch the wily bidders and note down sales. She sips warm water to keep her voice strong and pushes on for an hour or more, often selling over a million kilos of tea, managing transactions for about half a million dollars every hour on split second decisions. Buyers consult the signature yellow catalogue of John Keells, tap elaborate numbers into their calculators and mutter discreetly into their mobile phones.

“I had no idea what I was getting myself into,” she confessed, but with three uncles in the tea industry, she was ushered into a job right after school that was every bit of a challenge as promised. Auctioneers are the crucial link to plantations that depend on them to get the best possible price for their tea. It is a dual responsibility as auctioneers have to ensure the plantations get the best price while offering the buyer a reasonable bargain.

“About 10 years before I joined, there was one woman auctioneer and a few others have tried it out after me but I’ve done it the longest,” she says, proudly admitting it was a tough start in the male-dominated industry. She credits her experience as a national colours athlete in her school days for toughening her up for the auctioneer task and admits she was groomed from the start, partly because of her sports reputation.

“I was worried that people would see me as a ‘fast number’. At the beginning there were some that had the wrong idea and tried to put me down but my superiors were supportive and that helped. It’s important to stand on your own.”

Her willingness to take up the challenge and stick to it was not without its personal dimension.

Barely a year after she joined her father died and the additional pressure of family responsibility kept Daluwatte focused, a fact that she is now grateful for. Just three months into her job she was asked to cut her teeth with the smallest catalogue, mock auctions were held at office and home, and the day arrived.

“I used to practice in front of the mirror and my family chipped in by posing as my ‘buyers’ at the mock auctions I held at home. But they didn’t understand how a tea auction is different from conventional auctions and the bid is sometimes done covertly so I had to remind them not to make obvious gestures,” she remembered fondly. Then the fateful day arrived.

“I was really nervous. So few had seen a woman auctioneer that buyers started piling into the room, soon they was only standing room and then my boss walked in.” Daluwatte tried to get out of selling by asking the senior auctioneer sitting next to her to continue, but failed. “In the end I got the best prices for the company that week.”

“It’s like rapping,” she said, describing the pace auctioneers have to maintain. Practice helps and she has long been one of about a dozen auctioneers employed by the company. In an environment where even the boys find it challenging to take the gavel, Daluwatte rightly claims a position in the history books. She believes it is “high time” more women took up the gavel and has led the way by selling the largest catalogue of John Keells.

Each of the eight brokers have a different coloured catalogue and their selling times are roistered. Tea brokers form the golden link between plantations that produce tea and buyers that sell it to the world. The latter pick up the red, yellow or blue booklets, study their contents, consult their international partners and taste most of the mind boggling 12,500 lots or invoices that are delivered by brokers on every Friday and Monday to each company, usually in three versions making up for 37,500 individually labelled samples.

The cycle is repeated 50 times a year and the Colombo auction handles 300 million kilos of tea annually, significantly more than a handful of other auctions sprinkled across Kenya, Bangladesh and India. Colombo also produces the largest variety of teas found at any auction, close to 40 types made in 700 odd factories sourcing from thousands of acres of tea on the hills and plains of Sri Lanka.

Anslem Perera’s passion for tea

Buyers usually start prepping for an auction a fortnight before when the samples are delivered to them, explained Anslem Perera, who joined the industry in 1969, eventually going on to found one of Sri Lanka’s best known home grown tea brands, Mlesna, in 1983. It is now sold in 55 countries. His two sons have followed him into the business and often sit in on the same auction their father did decades ago when most plantations in Sri Lanka were still owned by the British.

Perera, whose passion for tea has made him a walking almanac, entered the profession with Brooke Bond, a monolithic British company founded in 1845 and in its heyday was more famous than Lipton with companies spanning the globe from Canada to Australia.

“It was the first job I ever applied to; after five interviews I was hired and made a trainee tea taster.”

Tea sommelier is still the starting point for many who join the industry. They are assiduously taught to evaluate, recognise, buy, blend and finally packet tea for export. Tea tasting is taught to planters to ensure quality production, brokers to identify what they are selling and for buyers to blend what the world demands.

When Perera began his time at the tea auction, it nestled in a thick-walled Dutch building in the Colombo Fort area with only one-third of the current number of buyers.

“The discipline now is certainly not what it used to be,” he mused sipping a light tea in his boardroom. “Back then we had to be in office at six in the morning on auction days, send the peons on their motorbikes to collect cables from international buyers, carefully decipher them using thick decoder books and be promptly seated at our designated tables at 7:45 a.m. as the auction began at 8 a.m. sharp.”

Tardiness was not allowed. If a buyer was late, he was locked out. The auctioneer was addressed as “Sir”. Tea was served to each person by a white-coated and brass buttoned peon who knew every buyer by name and custom-mixed their teas from an elegantly set tray. A beer and club sandwich was served at 5 p.m. If the auction dragged beyond 8 p.m. a single glass of scotch was placed before Perera and his colleagues.

“We never did anything to excess,” he insisted, “but everyone understood how to do business right.” If a small buyer needed a popular type of tea that could be made more expensive by excessive bidding, all he needed to do was lean over and courteously request, “Sir can I have the next line?” and a fair price would be allowed with bigger companies sitting out the bid – a practice that exists even today.

British men, dressed head to toe in white, many sporting handsome moustaches, sit behind curved teak and steel tables. Their spotless shoes resting on oak lined floors. The auctioneer is frozen in mid-bid mode. Sri Lankans or “natives” as they were referred to cluster at the back of the small room. Giant fans hang motionless from the high ceiling. The black and white photo hangs in Perera’s office, he gets a secretary to place it on the table to compare with a print of the London auction, for that is where it all started.

Ceylon Tea

The legendary London Tea Auction began in 1680, mainly to sell tea from China and India, which was then dominated by the British East India Company. The company was notoriously corrupt and practiced closed door selling until Thomas Twining, founder of Twinings, demanded it be sold by “public outcry” to ensure transparency. The London Auction endured, featuring in the Boston Tea Party and regrouping after each World War for 318 years, till 29 June 1998 when its gavel was silenced forever. Colombo was then handed the crown of oldest operating auction in the world.

The two auctions have startling resemblances, from suited buyers to candlelit auctions, which Perera recalls. Tea came to Sri Lanka almost as an answer to a desperate prayer. Ceylon was initially populated with coffee plantations from the 1820s, barely five years after it was colonised by the British. But a leaf-rotting disease set in 40 years later and an estimated 300,000 acres had to be uprooted and burned; in the end the blight won. With the colonial economy threatening to collapse, panicked planters frantically experimented with other crops but it was a reclusive Scotsman named James Taylor armed with tea who saved the day.

Taylor, a planter himself, successfully farmed tea in his estate Loolecondera near the hill town of Kandy, where remnants of his original bushes still draw locals and tourists. By the 1860s other despondent planters were travelling to his estate to learn how to grow the crop that would swiftly become the island’s largest export.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes, described the momentous rejuvenation in his short story ‘De Profundis’, writing ‘the tea-fields of Ceylon are as true a monument to courage as is the lion at Waterloo’.

Commercial cultivation of tea began in 1867 and just six years later records show 23 pounds of Ceylon tea from Loolecondera travelled to the London auction but such a tiny quantity was not entered in catalogue for public sale. Two boxes came under the hammer on 18 August 1875 and were shipped as “Sundry exports from Ceylon to New York. Tea, Duke of Argyll,” according to the public ledger dug up by historians.

As production rose rapidly in Ceylon, it became essential to ship out large tea chests regularly so the Colombo auction was born as a counterpoint to its London predecessor. 0n 30 July 1883 the first Colombo Tea Auction took place privately in the offices of Somerville & Company with just five lots that were left unsold. In 1894 the Colombo Tea Traders Association materialised and requested the Ceylon Chamber of Commerce, already 55 years old, to assist by providing a venue. The partnership has remained intact till now.

International buyers flocked to take advantage of the low prices and premium quality on offer. The wooden chests have given way to sacks, stiff suits have reduced to trousers and shirts but the emphasis on quality remains the same, contends Perera, who currently heads the Tea Traders Association.

“Ceylon Tea was the best in the world. All of the old generation remember this. Unfortunately we are letting the new generation forget it.”

Quality is still the main reason around 200 international buyers are entrenched in the Colombo Tea Auction, with about 80 attending weekly sessions. Despite slow global prices, Colombo auctions tea at a higher price than Kenya and India with volumes consistently larger than its competitors who prefer direct sales.

The local trade has also been hit by unrest in the Middle East, especially Iran and Iraq that are the number three and four buyers of Ceylon Tea. Sales to Turkey and Russia have held steady though affected by erratic weather patterns, helping to keep Sri Lanka the fourth largest tea producer in the world behind China, India and Kenya. In 2014 the South Asian island exported $ 1.5 billion worth of tea, the second biggest foreign exchange earner providing jobs to one in every 10 of the 20 million population.

Many of the trade’s older families, such as largest exporter Akbar Brothers begun in 1972 by patriarch Abbas Akbarally, have their grandsons in the industry. Others such as famed Imperial Teas, Jafferjee Brothers, Heritage Teas and Dilmah are all run by families, usually father-son duos though daughters are also starting to trickle in.

The Colombo Tea Auction is the backbone of a deeply traditional and people-centred industry that continues to flavour Sri Lanka, a sip at a time.