Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Wednesday, 16 September 2015 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

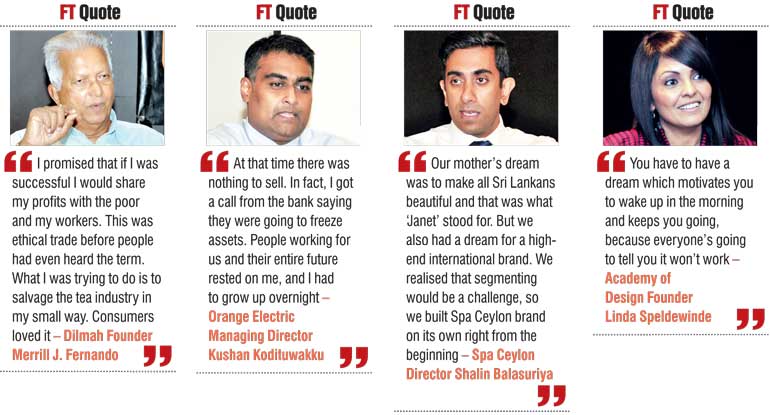

From left: SLID Chairperson Shiromal Cooray, Spa Ceylon Co-founder Shalin Balasuriya, Dilmah Tea founder Merill J. Fernando, The session moderated by Daily FT Founding Editor Nisthar Cassim, Academy of Design and International Design Campus Founder Linda Speldewinde and Orange Electric Managing Director Kushan Kodituwakku

By Sharon Dinasha Stephen

Today’s successful entrepreneurs have fame to rival rock stars, with movies being made about them, and their biographies flying off shelves as people try to pinpoint and emulate that ‘X’ factor that helps them make the right things happen. Is it luck? Their ability to spot opportunity? Their innovativeness and initiatives are applauded and envied, as they hurdle the risks between them and their goals.

And the risks are undeniable; according to Bloomberg, eight out of 10 start-ups fail within the first 18 months. Few dare to take that leap, but as the Sri Lanka Institute of Directors put it, ‘Who dares, wins’. Their insightful forum, thus named, featured a keynote by Merrill J. Fernando and was held at the Ivy Room of the Cinnamon Grand, attracting an audience of seasoned professionals as well as the young, the ambitious, and the entrepreneurial.

I dreamed a dream

To a spellbound audience, Fernando laid out his professional journey, painting a vivid picture of the tea trade as it was then, and the apparently insurmountable obstacles that beset him. He spoke of how the British had given the Sri Lankan brand of tea the strength to carry any other tea it was mixed with, but even in those early days, he foresaw a time when Ceylon tea, diluted in this way would lose its value and demand. He brought to life a time when Lankans were selling this valuable product in its raw material form and watching foreign companies be enriched by the value addition in packaging and branding, and the margins created by mixing in other teas.

Seeing this, he thought seriously about creating his own brand. But it appeared just a young man’s dream. He hadn’t the wherewithal for that kind of venture, and he would have to risk everything – he had no knowledge and experience, only the will to make it happen – so he spent that time dreaming and strategising. At a time when everybody thought there was something wrong with having your own brand, he felt that there was a strong force pushing him to do it.

He recalled fondly the 18 employees he had in 1962 when his dream was becoming a reality, saying, “Their loyalty, dedication and love for their work have made Dilmah and me.”

That dedication was critical as he took his product to Australia and New Zealand. He says he was told that the multinationals selling commoditised tea knew exactly what the consumer wanted so he would not be able to compete. “I had a lot of sympathetic opposition,” he recalled wryly, noting that there was resistance amongst those worried about potential trade disruption.

But that just got his fighting spirit fired up and he put in extra effort. “Fighting the government, tea board, trade, everybody in the country plus my competitors in Australia and New Zealand wasa battle I would have lost if not for the force that was driving me. I would not give up.”

Echoing the thought that Shiromal Cooray (Chairperson, SLID) voiced in the welcome address, that good governance should be considered a means to enhance performance, and a culture embedded in the organisation, he recollected, “I promised that if I was successful I would share my profits with the poor and my workers. This was ethical trade before people had even heard the term. What I was trying to do is to salvage the tea industry in my small way. Consumers loved it.”

What’s in a name?

Consumers also loved the ethos that had him naming the brand after his two little sons. Noting that brands everywhere search for just the right name, Nisthar Cassim, in his capacity as moderator, elicited more about what made Dilmah – Dilmah.

He had been looking for something which would resonate with housewives, admitted Fernando, and this one, using the names of his two little sons, hit just the right spot. He’d actually started with ‘Dilma’, but on a serendipitous suggestion, added the ‘h’ to balance it. “When I said it was named after my sons, it had emotional appeal. He’s not forcing us to buy it, he’s saying try it. Naming my brand after my children and putting my face on the advertising was the best investment I could have made, because it brought integrity back to tea.” But, he jokes, “I put my face on the pack because I couldn’t afford a celebrity!”

Orange Electric Managing Director Kushan Kodituwakku had a very different challenge. The company that is now Orange Electric began as Clipsal Lanka, a joint venture with Clipsal, an Australian firm. When Clipsal Australia was sold to a French multinational, rather than divest himself of the company, he decided to launch Orange Electric. He told the audience that it was the Sri Lankan dealers and electricians that played a pivotal role in the brand’s success by recommending it to customers and assuring them of its quality, elaborating: “Again it was because of the family relationship, and because multinationals don’t have a face. We talked to them and said ‘Look, we’re taking this stand for Sri Lanka’ (rather than selling to a foreign company).” The name ‘Orange’ was derived from ‘Orient Range’, but in a curiously coincidental turn of events, he revealed, he found out later that his grandfather’s first business just happened to be… transporting oranges!

Speaking of his experience launching the Spa Ceylon brand, Director Shalin Balasuriya said: “Our mother’s dream was to make all Sri Lankans beautiful and that was what ‘Janet’ stood for. But we also had a dream for a high-end international brand. We realised that segmenting would be a challenge, so we built Spa Ceylon brand on its own right from the beginning.”

When asked why ‘Ceylon’ was chosen rather than ‘Sri Lanka’, he revealed that at the time, Sri Lanka was associated mainly with the war and terrorism, whereas Ceylon, besides having an air of age-old mystique, had a lot of positive energy. Fernando added, “In tea, Ceylon is synonymous with quality. We destroyed a very valuable brand name associated with Ceylon Tea, when for political reasons the name of the country was changed to Sri Lanka.”

Academy of Design, in contrast, although a unique representative of the country’s talent, has a name that is not restricted by geography. And as Linda Speldewinde, its founder, noted, “AOD has become a regional brand and holds attraction as a unique proposition to regional and even foreign students.”

Jump-starts and driving forces

She noted that what drove her to establish AOD was comparable to what prompted Fernando’s long-time dream to restore Ceylon tea’s cachet and get the brand on everybody’s lips. “When I started, the apparel industry was on its knees and Sri Lanka was about to lose the quota; and I saw that the saving grace for this huge industry was the design. So I was trying to do the same thing with apparel (move up the value chain), working with young talent to build a brand for Sri Lanka.”

While she chose the fashion industry to focus on initially, entrepreneurship is her true love: “I don’t classify myself as a fashion or design person but as an entrepreneur. I don’t come from a family of entrepreneurs, but what inspires me is the impact of entrepreneurship.” Having worked with entrepreneurs at the grassroots level and seen the difference it makes, she is not discouraged by doubters.

“You have to have a dream which motivates you to wake up in the morning and keeps you going, because everyone’s going to tell you it won’t work.” Asked about the perceived lack of female entrepreneurs, she observed that need often spurs people to take that initial step: “Women’s entrepreneurship happens a lot at the grassroots level. In Colombo, I find that it’s more difficult, perhaps they don’t want to leave their comfort zone. I believe women have a really good formula naturally to push them to become entrepreneurs.”

Kodituwakku rather than starting off an entrepreneur, was an industrial engineer who jumped into entrepreneurship at the deep end as he took over the business when his father passed away. Asked what kept him going and why he didn’t sell the business instead of trying to run it at his young age, his deadpan response was: “At that time there was nothing to sell. In fact, I got a call from the bank saying they were going to freeze assets.”

He recalled his sense of responsibility: “People working for us and their entire future rested on me, and I had to grow up overnight.” He was also faced with building an entirely new (and very young) management team because the old guard didn’t want to work for someone so young. To add to the pressure, he said, his father, as an entrepreneur, had been closely involved in every aspect of the business and done everything. However having to learn on the fly didn’t deter him from accomplishing his ambitious goal to take the company to a billion rupees; “Everybody laughed, but in five years we grew tenfold.”

For Balasuriya, the toughest audience was the one at home: “The first hurdle was to convince Sri Lankans in the market for high-end products that it was alright to use a Sri Lankan product.”

As a member of the audience pointed out, each of the panellists had been laughed at and faced resistance in the beginning. Their making good on their dreams despite this serves as encouragement to those with radical ideas who are just starting out surrounded by naysayers. As an instructive and entertaining video displayed at the event stated, “Entrepreneurs aren’t prophets. They don’t predict the future, they create it.”

Lessons learnt

Sharing what they’ve learnt through their experience, the panellists stressed the need for cooperation and synergy. Fernando’s recommendation that the entire industry work together was passionate; “When each tries to exploit the other, they are collectively destroying the tea industry. Smallholders don’t get a fair price although they do a good job. Get together. If the industry worked as one unit, we would earn double or triple what we do now.”

While speaking of the great interest in business in our current post-war environment, Balasuriya noted that many are reluctant to be the first because they feel that not all elements are in place. He recommends a more proactive approach, creating opportunity and a first-mover advantage: “You can look at absence of factors as something that is going to hinder your industry, or you can create that infrastructure.”

Kodituwakku suggested a different approach, gleaned from his experience with supplying products to foreign markets; “When we said our products were from Sri Lanka, people wanted them cheaper than Chinese products, even though our manufacturing plants were equivalent to European standards. We got around that by opening offices in each region.” That strategy gave them much easier access to foreign clients, even though the products were still manufactured here.

Saying “It is only through challenges that we find ways to grow,” he shared interesting insights from those he has encountered. “You don’t have to manufacture every component in Sri Lanka to be a Sri Lankan company on a global stage,” he points out making the point that it is much more feasible from a business standpoint to source components that are not as easily produced here from other countries, but that does not dilute the ‘Sri Lankan-ness’ of the brand.

He is opposed to reducing quality to compete on cost, and advised those present to ‘Take the higher ground’. Fernando concurred, “Never compete at the bottom because others can always go lower and compromise on quality.”

The question of whether to build the brand first or whether to focus on efficiency first to ensure that quality which would then create attention for the brand was raised.

Fernando responded, “In tea, the advantage I had was that Ceylon tea had done the work for me, and the product/ business was there. So I had only to build the individual brand.” He reminded the audience that the message needs a place to focus the communication on, “Initially develop a brand to carry your message, then the message follows.”

From Kodituwakku’s experience, he related that everything had to be done simultaneously in his case. “I put IT infrastructure in place very early on. In manufacturing, we used 5S, and placed equal weightage on getting both the processes and brand in place.”

Fernando’s creed for a young entrepreneur’s success, garnered from all his experience is: “I now say primarily integrity of purpose and product, a warm heart and an open hand.”

Cassim, whose adept moderation of the session prompted a sharing of wisdom from panellists rarely observed on the same stage, concluded on a very fitting note: “The art of entrepreneurship is the art of possibility.”

The Annual Corporate Sponsors of the forum, whose support brought about the gathering and sharing of expertise, were Aitken Spence PLC, Union Assurance PLC, and First Capital Holdings PLC.