Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Monday, 10 July 2017 00:12 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Madushka Balasuriya

What is the biggest crisis facing the world today? War? Famine? Global warming? A sound case could be made for each, but in terms of immediacy and across the board impact, they all pale in comparison to the looming global water shortage creeping up on us – something a vast majority of the populace don’t even seem to be aware off.

This lack of awareness is especially odd considering water crises are year-on-year atop the pile of significant issues facing the planet, as per the World Economic Forum’s annual Global Risks Report. The United Nations, for its part, has predicted that nearly half the world’s population will be living “in areas of high water stress” by 2030.

Mina Guli - Pic by Lasantha Kumara

Mina Guli - Pic by Lasantha Kumara

However, even dire warnings such as these are swiftly brushed aside by most, primarily due to a lack of understanding about exactly how much we as a species depend on water. This is where Mina Guli comes in.

Guli is the marathon runner who hates to run. “I don’t really enjoy running,” says the 46-year-old Australian native, who just two months ago completed 40 marathons in 40 days, a total of 1,688km. “I do it because it’s a way for me to go and visit people on the ground and communities and for me to understand, from them, what this water crisis is all about.”

Guli is also a leading water advocate. Her work has gained global recognition and seen her featured in a plethora of international publications, most notably when she was named in Fortune’s list of 50 greatest leaders in the world – a list that also includes the Pope! All the accolades however are of secondary importance, for Guli has but one simple goal to draw attention to the planet’s increasingly scarce water resources.

“We as a civilisation don’t understand water, we don’t understand where water comes from, we don’t understand where it’s going, we don’t understand how it will be managed in the future. I think most of the people that I talk to, who live in big cities like this, think that because we turn the tap and water comes out, water will always come out.

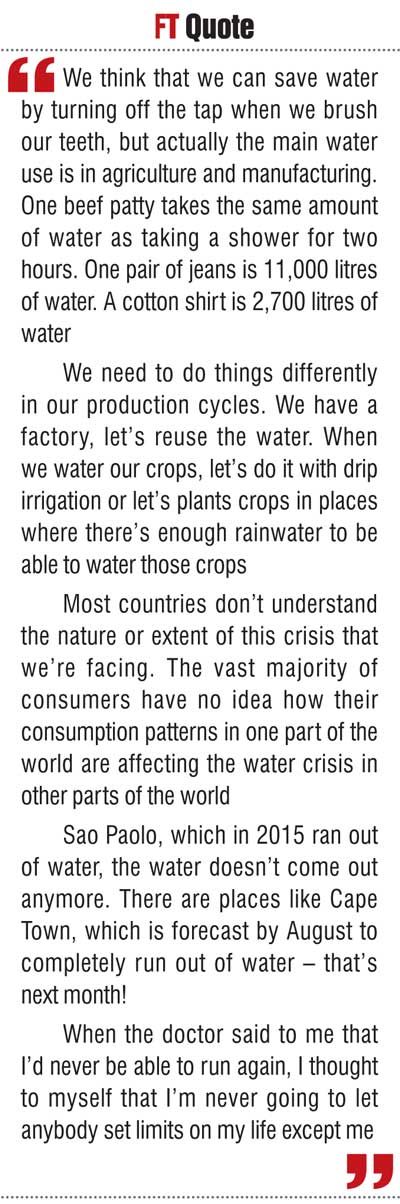

“But in places like Sao Paolo, which in 2015 ran out of water, the water doesn’t come out anymore. There are places like Cape Town, which is forecast by August to completely run out of water – that’s next month!”

For Guli, the extreme act of running 40 marathons in 40 days, all along six of the world’s major rivers, was one that she knew would simultaneously grab the attention of the public while also serving as a symbol for the message she was striving to deliver.

“The standard distance of a marathon is 42.2km. I chose marathons because I wanted to represent the 40% difference between demand and supply for water by 2030,” she explains.

“As for running 40 in 40 along the world’s six major rivers, the idea was to tell stories about how we are linked to rivers. I wanted to show that water is life and without water we have no life.”

Invisible water

At one point in my interview with Guli, I half-joked that she may have had just made the single greatest argument in favour of vegetarianism I had ever heard. Guli, who is in fact vegetarian, however wasn’t pitching a diet free of meat; she was explaining the concept of “invisible water”.

“We think that we can save water by turning off the tap when we brush our teeth, but actually the main water use is in agriculture and manufacturing. One beef patty takes the same amount of water as taking a shower for two hours. One pair of jeans is 11,000 litres of water. A cotton shirt is 2,700 litres of water.

“That’s the problem with the water crisis, we don’t understand how we’re connected to it. We think we’re connected by our taps when actually we’re connected by our purchasing behaviour. It’s this idea about invisible water. About making invisible water visible.”

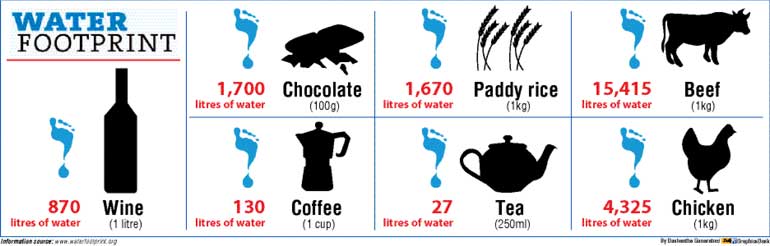

Indeed, knowing that one 125ml glass of wine costs 110 litres of water, or that the global average water footprint of pork is 5,990 litres per kg, are facts that many people would rather not think about. This is something Guli empathises with, suggesting that instead of going cold turkey, the best solution maybe to reduce your personal water footprint wherever possible.

“I’m vegetarian and have been for the vast majority of my life – because I think it’s the right thing to do – but I would never ever force it upon anybody else. I would however suggest to people that if they want to do one thing – and it’s an easy thing to do – it’s to go for something like a ‘Meatless Monday’.

“The second thing to do is to start asking questions as to where your stuff is coming from. Understand who made your cotton shirt or your pants or your socks or your shoes, and really start to reward the companies that are doing well by doing good.”

Smartphones and even smarter consumers

While cutting out meat from your diet, even just for a day, is fairly feasible, some of the other contributors to invisible water wastage are harder to steer clear of. Most prominently smartphones; a single smartphone takes roughly 13 tonnes of water to produce. This number of course varies slightly from manufacturer to manufacturer, but when all aspects of the production process (e.g. raw material mining) are taken into consideration, it is more or less the same across the board.

When you then consider the smartphone turnover rate among consumers, the numbers become even scarier. Nevertheless, asking someone, in this day and age, to give up their smartphone is borderline sacrilegious. Guli agrees, noting that one of the questions she’s been asked the most if she is anti-consumerism.

“[I am] absolutely not [anti-consumerism]. How many of us want to give up our smartphones? And even if we all did, how would that be good for our economies? What, are we all going to now start using less power? Are we gonna turn off the power 7 p.m. at night? That’s not a life that is sustainable for any of us, because a big part of sustainability is happiness. I’m not suggesting any of that for a minute.”

What she is suggesting though, is that consumers understand that they hold the power for change. Recent shifts in focus towards ‘green’ production practices by many companies are largely driven by consumer demand. The decrease in purchase of fur and animal-based products has reduced drastically over the years due to increased awareness. Guli hopes for the same, if not greater, impact by increasing awareness among consumers about the water footprints of their purchasing choices.

“We need a new brand of consumer. We need a brand of consumer that says, ‘we have to do things differently from the way our parents and grandparents did them, we have to do things in a way that is sustainable, and that allows us to have water for everyone, forever’.

“That means change. It doesn’t mean buying less, it means buying different. Looking at where your stuff came from, understanding it and thinking about it, and making a very deliberate choice about what you buy and where you buy it from. So we need to find those companies now that are prepared to stand out from the crowd and prepared to set new examples of how to do things right, and reward them for it so that others will follow.”

Reward companies that do good

The main way by which companies can affect meaningful change is in altering their production cycles, says Guli, so as to reduce water wastage.

“We need to do things differently in our production cycles. We have a factory, let’s reuse the water. When we water our crops, let’s do it with drip irrigation or let’s plants crops in places where there’s enough rainwater to be able to water those crops.

“Let’s not stop doing things, let’s just do things smarter. There’s the same amount of water on the planet as there has always been, the issue is that we’re wasting it,” she decries.

In Sri Lanka, companies such as apparel manufacturer Brandix are leading the way in this endeavour. In fact, it was Brandix that brought Guli down to Sri Lanka, so that she could better understand the impact local supply chains have on the country’s water supply.

“I’m very interested in this idea about supply chains. Where does our stuff come from? If I go to a shop and buy a cotton shirt that says made in Sri Lanka, what does that mean? If there’s a drought in the country, does that mean I’ve contributed to the drought?

“I wanted to come and understand, and now I have the opportunity to meet with Brandix which is one of the leaders in this space and is really very adamant that we can solve this water crisis.”

Brandix over the last few years has become a genuine leader in the water-conservation space, pioneering several initiatives to improve access to water in rural communities. In 2015-16 alone 367 water supply projects were completed, while the company has also made concerted efforts to improve the quality of water and sanitation in areas surrounding its factories.

“This is a company that’s doing good, it’s trying to set examples by using water efficiently, looking after the people, looking after the planet, and still making money at the same time. This kind of triple bottomline and leadership in this space is incredibly important. Because with leadership you can then encourage others to live up to the same standard.”

It’s never too late

“Water Advocate. Corporate Lawyer. Ultra Runner,” reads the home page of Guli’s website (www.minaguli.com), and this is indeed a neat summary of all that she is at present. What it doesn’t capture however is her struggle in reaching those titles.

It’s hard to imagine now but Guli despised sports as a kid. Ironically, it was a horrendous back injury suffered at the age of 22, one that doctors said would leave her unable to run for the rest of her life, that flicked a switch of sorts in Guli’s brain to take up running.

“When the doctor said to me that I’d never be able to run again, I thought to myself that I’m never going to let anybody set limits on my life except me.”

Nine months from that prognosis, Guli completed the Ironman Triathlon, a gruelling race that includes swimming, cycling and running.

“It is amazing how resilient the body is when the mind is determined, it is amazing what you can achieve when you believe in something bigger than yourself.”

It is this sense of self-determination, and an attitude of nothing being beyond reach, that lead Guli to embark on her life’s purpose solving the global water crisis. She hopes that her journey will provide inspiration for others to make changes, however small, within themselves.

“You don’t have to have special skills. I’m not a runner. You don’t have to be a runner to run, you don’t have to be special to do anything. There is no excuse not to pursue your dreams. Things are hard? Okay, so you overcome them. Things are challenging? Okay, figure out a solution. Things are bigger than you ever expected or you ever imagined before? So you find a way to get through it.

“Nobody has ever solved the water crisis before? It’s not an excuse. How do I know I can run 40 marathons in 40 days? How do I know I can run 100 in 100? I don’t, but I believe I can and that’s what matters.”

Change in perspective

Change in perspective

Guli repeatedly states how “horrified” she was to have lived in Australia for 10 years in the middle of a drought and never understood the water footprint left behind by her daily consumption. Having travelled to every continent and a countless number of countries, she says this is common theme among nearly everyone she has met.

“Most countries don’t understand the nature or extent of this crisis that we’re facing. The vast majority of consumers have no idea how their consumption patterns in one part of the world are affecting the water crisis in other parts of the world.

“By buying something made in Sri Lanka when I am situated anywhere else in the world, I am then connected to the water problems in Sri Lanka. So your water crisis, your drought, is not just your problem, it’s all of our problem. But what that means is, it is in the power of each of those consumers to make an impact in Sri Lanka by rewarding companies that are doing good things.”

Sri Lanka in particular has been of late buffeted by the effects of climate change, from droughts to floods. In the midst of this, there is also now a growing garbage problem. For Guli, this comes to signify one overarching issue water wastage.

“Think about how much water went into all that waste. That’s not a waste problem, that’s a water problem. Every time we see packaging, I don’t see packaging, I see water. I don’t see a plastic bag, I see a waste of water. I look at a plate of food that someone is throwing away in a rubbish bin, and I don’t think ‘oh you could’ve fed somebody who was hungry,’ I think ‘the planet used its water resources to make this food and now you’ve thrown it away’.

“For me, water is life, and it’s a life that is a better life when you have water in it. And it’s a life I want to leave for the next generation and the generation after them.”

To find out more on your water footprint, head to www.waterfootprint.org.